Validating Biosensor Performance: A Strategic Guide to Chromatographic Correlation for Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals on validating biosensor results using chromatography methods.

Validating Biosensor Performance: A Strategic Guide to Chromatographic Correlation for Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals on validating biosensor results using chromatography methods. It covers the foundational principles of biosensor technology and the gold-standard status of chromatographic techniques. The guide details methodological approaches for parallel testing, explores common challenges and optimization strategies using tools like Design of Experiments (DoE), and establishes robust protocols for statistical comparison and validation. By synthesizing current research and practical case studies, this resource aims to empower scientists to build confidence in their biosensor data, accelerating their integration into biomedical research and clinical applications.

Biosensors and Chromatography: Understanding the Fundamentals and Need for Validation

What are Biosensors? Principles of Biological Recognition and Signal Transduction

A biosensor is an analytical device that integrates a biological recognition element with a physicochemical transducer to detect a chemical substance [1]. This combination allows for the sensitive and selective detection of specific analytes, ranging from simple ions to complex proteins, cells, and pathogens. Biosensors have become indispensable tools across numerous fields, including biomedical diagnosis, environmental monitoring, food safety control, drug discovery, and bioprocess engineering [2] [3]. The fundamental principle governing all biosensors involves a bioreceptor that specifically interacts with the target analyte, leading to a change that a transducer converts into a measurable signal, typically optical or electrical, which is then processed for user interpretation [2].

The history of biosensors dates back to 1906 with M. Cremer's early work, but the field truly began with Leland C. Clark, Jr.'s development of the oxygen electrode (Clark electrode) in 1956, earning him the title "father of biosensors" [2]. His subsequent demonstration of an amperometric enzyme electrode for glucose detection in 1962 paved the way for the first commercial biosensor developed by Yellow Spring Instruments (YSI) in 1975 [2]. Since these early innovations, the field has expanded dramatically, evolving into a multidisciplinary area of research that bridges principles from physics, chemistry, biology, micro/nano-technology, and electronics [2].

Table 1: Key Historical Developments in Biosensors

| Year | Development | Key Innovator/Company |

|---|---|---|

| 1956 | First 'true' biosensor (Oxygen electrode) | Leland C. Clark, Jr. |

| 1962 | Amperometric enzyme electrode for glucose | Leland C. Clark |

| 1975 | First commercial biosensor | Yellow Spring Instruments (YSI) |

| 1983 | Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) immunosensor | Liedberg et al. |

| 1992 | Handheld blood biosensor | i-STAT |

Core Principles and Components of a Biosensor

A typical biosensor consists of four main components, working in sequence to detect and report the presence of an analyte.

The Bioreceptor

The bioreceptor is a biological or biomimetic element that provides the specificity for the biosensor. It is a molecule that specifically recognizes the analyte in a sample, even among other admixtures and contaminants [2] [4]. This bio-recognition event generates a signal in the form of light, heat, pH change, charge, or mass change [2]. Common types of bioreceptors include:

- Enzymes: Utilize specific binding capabilities and catalytic activity. The analyte may be converted into a detectable product, inhibit the enzyme's activity, or modify the enzyme's properties [1].

- Antibodies/Antigens: Exploit the highly specific binding affinity of an antibody for its target antigen, analogous to a lock and key fit [1].

- Nucleic Acids (DNA/RNA): Used in genosensors (based on complementary base pairing) or aptasensors (using synthetic aptamers that fold to recognize targets) [1] [5].

- Whole Cells & Tissues: Utilize microorganisms, organelles, or entire tissues as integrated sensing elements that can respond to stimulants like stress, toxicity, or metabolic changes [1] [5].

- Artificial Binding Proteins: Engineered protein scaffolds that mimic the binding function of antibodies but are smaller, more stable, and cheaper to produce [1].

The Transducer

The transducer is the element that converts the biological recognition event into a measurable signal [2]. This process of energy conversion is known as signalisation [2]. The primary transduction methods can be categorized as follows:

- Electrochemical: Measures changes in current (amperometric), potential (potentiometric), or impedance (impedimetric) resulting from the bio-recognition event [3]. These are dominant in clinical diagnostics due to their simplicity and sensitivity [3].

- Optical: Detects changes in light properties, such as absorbance, fluorescence, luminescence, or refractive index (e.g., Surface Plasmon Resonance) [4] [3]. These are favored in research for their superior multiplexing capabilities [3].

- Mechanical/Acoustic: Measures changes in mass or viscoelastic properties on a surface, often using piezoelectric crystals or microcantilevers, which results in a resonance frequency shift [3] [6].

- Thermal: Monitors the heat exchange (enthalpy change) produced by biochemical reactions [3].

Electronics and Display

This subsystem processes the transduced signal for interpretation. It includes complex electronic circuitry that performs signal conditioning—such as amplification and conversion from analog to digital form [2] [1]. The display unit then presents the results in a user-friendly format, such as a numeric, graphic, or tabular readout on a liquid crystal display [2]. This part often constitutes the most expensive component of the sensor device, though advancements in integrated systems, including CMOS-based microsensors, are helping to reduce costs and size [1].

Diagram 1: Fundamental Biosensor Architecture

Critical Performance Characteristics of Biosensors

The utility of a biosensor is gauged by several key performance characteristics, which must be optimized for reliable operation [2].

- Selectivity: This is the most critical feature. It is the ability of the bioreceptor to detect a specific analyte in a sample containing other admixtures and contaminants without interference [2]. For example, an antibody should interact only with its target antigen.

- Sensitivity and Limit of Detection (LOD): The sensitivity refers to the minimum amount of analyte that can be reliably detected by the biosensor. In many medical applications, biosensors are required to detect concentrations as low as nanograms or even femtograms per milliliter [2].

- Reproducibility: This is the ability of the biosensor to generate identical responses for a duplicated experimental setup. It encompasses both precision (the ability to produce alike results every time a sample is measured) and accuracy (the capacity to provide a mean value close to the true value) [2].

- Stability: This refers to the degree of susceptibility to ambient disturbances (e.g., temperature fluctuations) that can cause signal drift. It is crucial for applications requiring long incubation or continuous monitoring. Stability is influenced by the degradation of the biological element over time and the affinity of the bioreceptor for the analyte [2].

- Linearity: This attribute indicates the accuracy of the measured response for a set of measurements to a straight line, defined by y=mc (where c is the analyte concentration, y is the output, and m is the sensitivity). The linear range is the concentration range over which the biosensor response changes linearly, and it is associated with the sensor's resolution [2].

Table 2: Key Performance Characteristics of Biosensors

| Characteristic | Definition | Importance |

|---|---|---|

| Selectivity | Ability to detect a specific analyte in a complex sample matrix. | Prevents false positives from interfering substances. |

| Sensitivity (LOD) | Lowest concentration of analyte that can be reliably detected. | Enables detection of trace-level biomarkers or contaminants. |

| Reproducibility | Ability to generate identical responses for a duplicated setup. | Ensures reliability and robustness of the measurements. |

| Stability | Degree of susceptibility to ambient disturbances and signal drift. | Critical for long-term monitoring and shelf-life of the device. |

| Linearity | Accuracy of the response to a straight line over a concentration range. | Allows for accurate quantification of analyte concentration. |

Biosensor Validation: A Comparison with Chromatography Methods

Validating biosensor performance against established analytical techniques is a critical step in confirming their reliability, especially for environmental or clinical application [7] [5]. Conventional methods like high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and gas chromatography (GC), often coupled with mass spectrometry (MS), are considered gold standards due to their high accuracy, sensitivity, and reliability [5]. However, these techniques have limitations: they require high-cost instruments, complex sample preparation, time-consuming protocols, and labor-intensive processes, hindering real-time, in-situ monitoring [5].

Biosensors offer a promising alternative, providing advantages in speed, cost, portability, and suitability for on-site testing [5]. A key study demonstrates this validation paradigm, where an enzymatic biosensor was compared with liquid chromatography for monitoring organophosphorus pesticides and carbaryl in water [7]. The biosensor provided a rapid, cumulative signal for the total pesticide content in a sample, successfully distinguishing between water containing 3.9 μg/L and 10.3 μg/L of total target pesticides [7]. This "total signal" could serve as a positive indication of contamination, triggering further, more specific analysis if needed. The chromatographic method, in a subsequent step, was used to unequivocally confirm and quantify the individual pesticides and their metabolites [7]. This hybrid approach leverages the speed and convenience of the biosensor for screening with the high specificity of chromatography for confirmation.

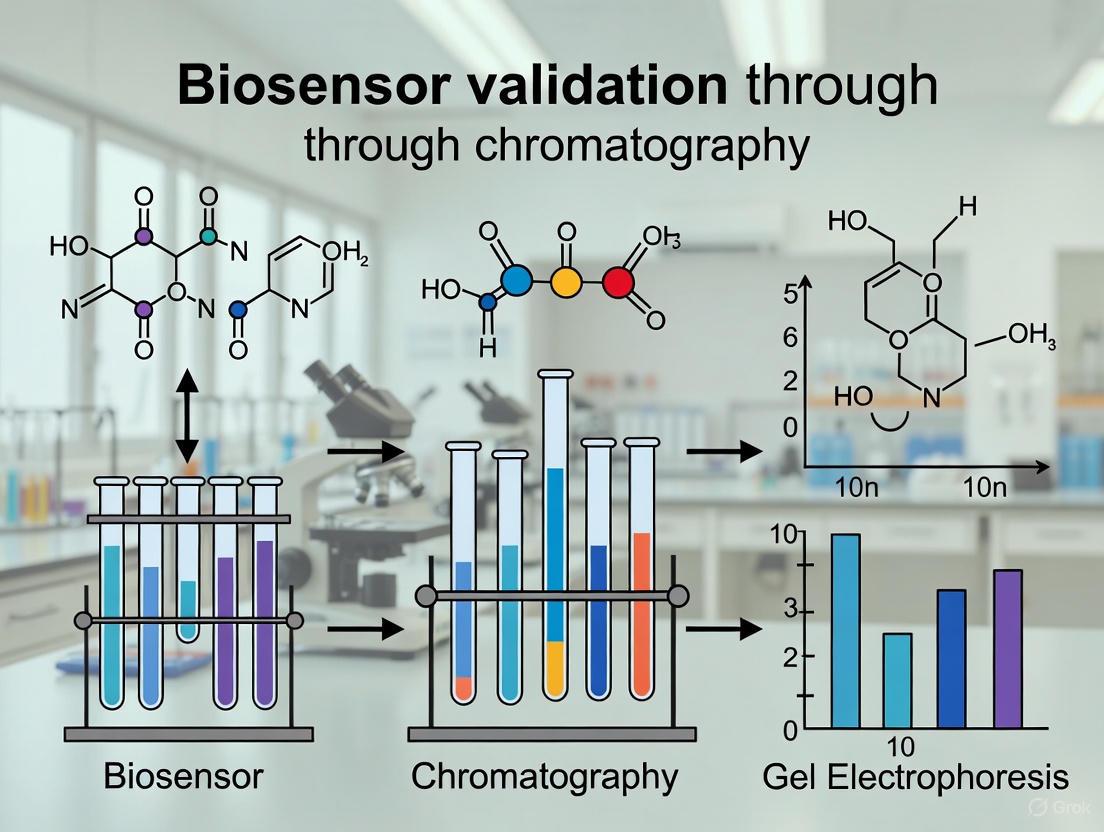

Diagram 2: Biosensor and Chromatography Validation Workflow

Experimental Protocol: Biosensor Validation for Pesticide Detection

The following methodology outlines the parallel analysis of water samples using biosensors and liquid chromatography, as derived from the validation study [7].

1. Biosensor Setup and Operation:

- Bioreceptor: The enzyme acetylcholinesterase (AChE) is immobilized on the transducer surface.

- Transducer Principle: The enzymatic reaction of AChE with its substrate (acetylthiocholine chloride) produces thiocholine, which dimerizes to a disulfide compound, generating a measurable electrochemical signal.

- Measurement: Organophosphorus pesticides and carbaryl act as AChE inhibitors. The sample is introduced to the biosensor, and the degree of enzyme inhibition is measured, which is proportional to the concentration of the pesticides present.

- Output: The biosensor provides a total signal corresponding to the cumulative inhibitory effect of all present pesticides.

2. Liquid Chromatography Analysis:

- Sample Preparation: The same water samples may undergo liquid-liquid extraction or solid-phase extraction to concentrate the analytes.

- Chromatographic Separation: The extract is injected into an HPLC system. A reversed-phase C18 column is typically used, and the pesticides are separated using a gradient of water and an organic solvent like acetonitrile or methanol as the mobile phase.

- Detection: A diode-array detector (DAD) or mass spectrometer (MS) is used for detection. The DAD captures the UV spectrum of each eluting compound, providing a unique fingerprint for confirmation [7].

- Quantification: The concentration of each individual pesticide and its metabolites is determined by comparing the peak area or mass spectral response to those of known standards.

3. Data Correlation:

- The total signal from the biosensor is correlated with the sum of concentrations of target pesticides obtained from HPLC.

- Statistical analysis (e.g., linear regression) is performed to establish the relationship between the two methods and determine the biosensor's accuracy and working range.

Advanced Developments and Future Perspectives

The field of biosensing is continuously evolving, driven by advancements in nanotechnology, material science, and data analytics.

The Role of Nanomaterials and Miniaturization

Reducing the size of biosensors to the micro- or nano-scale has proven beneficial for improving the signal-to-noise ratio and enabling the use of smaller sample volumes [2]. Nanomaterials, such as gold nanoparticles, graphene, and quantum dots, are extensively used to enhance sensitivity by increasing the effective surface area for bioreceptor immobilization and improving electron transfer in electrochemical sensors or optical properties in optical sensors [3] [8]. For instance, colloidal gold nanoparticles were the foundation for many rapid immunochromatographic tests (lateral flow assays) used globally during the COVID-19 pandemic [8].

CRISPR-Cas Integration

The convergence of CRISPR-Cas technology with biosensing presents a powerful new frontier for diagnostics. CRISPR systems can be programmed to detect specific nucleic acid sequences with exceptional specificity. When combined with nanomaterials for signal enhancement (leveraging catalytic, colorimetric, or fluorescent properties), CRISPR-based biosensors offer massive potential for advancing point-of-care clinical diagnostics [8].

Artificial Intelligence and Deep Learning

A significant challenge in biosensing is improving accuracy and reducing false results. Artificial intelligence (AI), particularly deep learning, is being applied to address this. One approach uses a theory-guided recurrent neural network (TGRNN) to classify the dynamic response of a biosensor, such as a DNA-functionalized cantilever detecting microRNA [6]. By training the model with data that is consistent with the theoretical principles of surface-based binding, researchers have achieved high prediction accuracy (~98.5%) and reduced the likelihood of false-positive and false-negative results, even when using only the initial transient response, thereby speeding up the assay time [6].

Systematic Optimization via Design of Experiments (DoE)

Optimizing the many parameters in biosensor fabrication (e.g., bioreceptor density, immobilization chemistry, detection conditions) is complex. The Design of Experiments (DoE) chemometric tool provides a systematic, statistically sound methodology for this purpose, moving beyond inefficient one-variable-at-a-time approaches [9]. DoE considers the interaction between variables and allows for the construction of a data-driven model to find the global optimum conditions, which is crucial for developing reliable and ultrasensitive biosensors for point-of-care diagnostics [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Biosensor Research and Development

| Item | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) | Enzyme bioreceptor for pesticide detection. | Inhibitor-based detection of organophosphates and carbamates in environmental water [7]. |

| Monoclonal Antibodies | High-specificity bioreceptors for immunosensors. | Capture and detection of protein biomarkers like IL-17A or C-Reactive Protein (CRP) in serum [4]. |

| DNA/Aptamer Probes | Nucleic acid-based bioreceptors for genosensors/aptasensors. | Detection of microRNA (e.g., let-7a) using thiolated-DNA probes on a cantilever or electrode surface [6] [1]. |

| Gold Nanoparticles | Nanomaterial for signal enhancement and labeling. | Colorimetric signal generation in lateral flow immunoassays; enhancing surface plasmon resonance [8]. |

| Isotype Control Antibodies | Critical negative control reagents for immunoassays. | Differentiating specific binding from nonspecific binding (NSB) in label-free optical biosensors [4]. |

| Photonic Ring Resonator (PhRR) Chips | Label-free optical transducer platform. | Silicon nitride chips fabricated via CMOS processes for highly sensitive refractive index-based detection [4]. |

| Screen-Printed Electrodes (SPEs) | Low-cost, disposable electrochemical transducer platform. | Base for amperometric or impedimetric biosensors; suitable for point-of-care testing [3]. |

Liquid chromatography techniques, particularly High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) and Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS), represent the cornerstone of modern quantitative bioanalysis. These methods provide the rigorous analytical validation necessary for pharmaceutical development, clinical monitoring, and environmental analysis. Within the context of emerging biosensor technologies, chromatographic methods serve as the reference standard for validating novel detection platforms, offering unparalleled specificity, sensitivity, and precision. The fundamental principle underlying chromatography's gold standard status is its physical separation of analytes prior to detection, which effectively eliminates matrix interference and enables definitive identification and quantification of target compounds in complex biological matrices. This article provides a comprehensive comparison of LC-MS/MS and HPLC methodologies, detailing their operational principles, performance characteristics, and essential role in verifying the accuracy of rapid screening technologies such as biosensors.

Fundamental Principles and Instrumentation

HPLC operates by pumping a liquid sample and mobile phase at high pressure through a column packed with solid adsorbent material, separating components based on their differential partitioning between the mobile and stationary phases. Detection is typically achieved via ultraviolet-visible (UV-Vis), photodiode array (PDA), or fluorescence detectors, which identify compounds based on their optical properties. The technique excels in resolving complex mixtures but requires analytes to possess specific chromophores or fluorophores for detection [10].

LC-MS/MS represents a more advanced hyphenated technique that couples the separation power of liquid chromatography with the exceptional detection capabilities of tandem mass spectrometry. After chromatographic separation, analytes are ionized (commonly via electrospray ionization), separated in the first mass analyzer based on their mass-to-charge ratio, fragmented through collision-induced dissociation, and the resulting product ions are analyzed in the second mass analyzer. This two-stage mass analysis provides structural information and significantly enhances specificity, making it ideal for complex matrices [11] [12].

Comparative Analytical Performance

The table below summarizes key performance parameters for HPLC and LC-MS/MS across critical analytical metrics, illustrating their respective strengths and appropriate applications.

Table 1: Performance Comparison Between HPLC and LC-MS/MS

| Analytical Parameter | HPLC with UV/PDA Detection | LC-MS/MS |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Sensitivity | ng to µg range | pg to fg range [11] [13] |

| Specificity | Moderate (based on retention time and spectral matching) | High (based on retention time, precursor ion, and fragment ions) [11] |

| Analysis Speed | Moderate to Fast (5-30 minutes) | Fast (2-8 minutes) [11] [13] |

| Matrix Effect Tolerance | Lower (susceptible to co-eluting interferents) | Higher (MRM overcomes many interferents) [10] |

| Structural Information | Limited (spectral libraries for identification) | Comprehensive (fragmentation patterns for structural elucidation) [12] |

| Applicability | Compounds with chromophores/fluorophores | Virtually all ionizable molecules [10] |

| Cost and Operational Complexity | Lower | Higher |

The evolution from HPLC to UPLC (Ultra-Performance Liquid Chromatography) with sub-2μm particles has further enhanced separation efficiency, reducing analysis times to 2-5 minutes per sample while maintaining resolution [12]. LC-MS/MS particularly excels in targeted quantitative applications using Multiple Reaction Monitoring (MRM) mode, where it monitors specific precursor-product ion transitions for each analyte, providing exceptional selectivity even in challenging matrices like plasma, serum, and tissue homogenates [11] [13].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard LC-MS/MS Protocol for Antimicrobial Analysis in Serum

The following protocol, adapted from a validated method for detecting antimicrobials in human serum, exemplifies the rigorous approach required for reliable quantitative analysis [13]:

Sample Preparation (Solid Phase Extraction):

- Pipette 200 μL of serum sample into a microcentrifuge tube

- Add 10 μL of internal standard solution (stable isotope-labeled analogs)

- Add 190 μL of phosphoric acid for protein precipitation

- Vortex mixtures vigorously for 30 seconds

- Centrifuge at 13,000 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C

- Transfer 300 μL of supernatant to preconditioned Oasis HLB μElution SPE cartridge

- Wash twice with 150 μL water

- Elute with 150 μL of 60% (v/v) acetonitrile in water

- Collect eluate in clean test tube for analysis

Chromatographic Conditions:

- Column: CORTECS T3 (100 × 2.1 mm, 2.7 μm)

- Mobile Phase: A) 0.1% formic acid in water; B) 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile

- Gradient: 5% B (0 min) → 60% B (5 min) → 90% B (5.5 min, hold 1 min) → 5% B (6.6-8 min)

- Flow Rate: 0.3 mL/min

- Column Temperature: 35°C

- Injection Volume: 2 μL

Mass Spectrometric Parameters:

- Ionization: Electrospray Ionization (ESI) positive mode

- Ion Spray Voltage: 4500 V

- Source Temperature: 500°C

- Curtain Gas: 20 psi

- Nebulizer Gas (GS1): 50 psi

- Auxiliary Gas (GS2): 50 psi

- Detection: Scheduled Multiple Reaction Monitoring (sMRM)

- Data Acquisition: Analyst 1.6.3 software

- Data Processing: MultiQuant software (version 3.0.2)

This method achieved excellent linearity (R² > 0.999) across 0.5-50 ng/mL range, with inter- and intra-assay precision <12.0% and accuracy of 86.1-109.0% for nine antimicrobial compounds [13].

HPLC Protocol for Traditional Medicine Quality Control

For quality control of complex natural products like Lonicera japonica Thunb., the following HPLC method provides reliable quantification of major active components [10]:

Sample Preparation:

- Accurately weigh 0.5 g of powdered plant material

- Add 50 mL of 70% methanol and extract via ultrasonication for 30 minutes

- Centrifuge at 5000 × g for 10 minutes

- Filter supernatant through 0.22 μm membrane prior to injection

Chromatographic Conditions:

- Column: Waters ACQUITY UPLC HSS T3 (2.1 × 50 mm, 1.8 μm)

- Mobile Phase: 0.1% formic acid in water (A) and acetonitrile (B) with gradient elution

- Flow Rate: 0.4 mL/min

- Column Temperature: 40°C

- Detection: PDA detector (330 nm for chlorogenic acid, 350 nm for flavonoids)

- Injection Volume: 2 μL

This method successfully quantified eleven analytes with limits of quantification reaching 0.005-0.56 μg/mL, demonstrating excellent linearity (regression coefficients >0.9991), recovery (98.78-105.13%), and precision (RSD < 3.91%) [10].

Chromatography as a Validation Tool for Biosensor Technologies

Correlation Studies Between Biosensor and Chromatographic Methods

The validation of biosensor performance against chromatographic reference methods is essential for establishing their reliability in analytical applications. The table below illustrates representative correlation data between biosensor platforms and their corresponding chromatographic validation methods.

Table 2: Biosensor Validation Against Chromatographic Methods

| Biosensor Type | Target Analyte | Chromatographic Validation Method | Correlation Coefficient (R²) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPR-based biosensor | Chlorogenic acid (3-CQA) | UPLC-PDA-QDa | 0.9991 (for quantification) | [10] |

| Electrochemical DNA biosensor | Leuprolide | LC-MS/MS | Comparable results (full validation) | [11] |

| Whole-cell biosensor (E. coli) | Pyrethroid insecticide | LC-MS/MS | Detection limit: 3 ng/mL | [5] |

| Enzyme-based biosensor | Various pesticides | HPLC-UV | >0.995 for standard curves | [5] |

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) biosensors have demonstrated particular utility in drug discovery applications, enabling real-time monitoring of biomolecular interactions without labeling requirements. In one study, SPR was employed to investigate the inhibitory activity of chlorogenic acid (3-CQA) from Lonicera japonica Thunb. against TNF-α, revealing a binding affinity (KD) of 1.38 × 10⁻⁶ M. These interaction results were subsequently validated using UPLC-MS quantification, confirming both the binding affinity and concentration of active compounds [10].

Addressing Biosensor Limitations Through Chromatographic Validation

Chromatographic methods play a crucial role in identifying and overcoming key limitations of biosensor technologies, including:

Matrix Interference: Biosensors frequently suffer from nonspecific binding and matrix effects in complex samples. LC-MS/MS validation helps identify these interferences through precise separation and detection of individual components [5]. For instance, in therapeutic drug monitoring of leuprolide, an LC-MS/MS method with solid phase microextraction (MEPS) clean-up achieved a lower limit of quantification of 0.0500 ng/mL in human plasma, significantly surpassing the performance of immunoassays which suffer from cross-reactivity issues [11].

Specificity Challenges: While biosensors utilizing enzymes, antibodies, or aptamers offer targeted recognition, they may exhibit cross-reactivity with structurally similar compounds. Chromatographic separation prior to detection definitively resolves individual analytes, as demonstrated in the simultaneous determination of nine antimicrobials in pregnant women's serum, where LC-MS/MS identified specific compounds that immunoassays could not distinguish [13].

Quantification Accuracy: Biosensor response can be affected by environmental conditions, sensor drift, and fouling. Chromatographic methods provide absolute quantification through calibration with certified reference materials and internal standards, such as stable isotope-labeled analogs in LC-MS/MS, which correct for extraction efficiency and ionization variations [11] [13].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The successful implementation of chromatographic methods requires specific high-quality reagents and materials. The following table details essential research solutions for method development and analysis.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Chromatographic Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Internal Standards | Correct for variability in extraction and ionization; enable precise quantification | Leuprolide-¹³C₆-¹⁵N for LC-MS/MS assay of leuprolide in plasma [11] |

| Solid Phase Extraction Cartridges (Oasis HLB) | Sample clean-up and analyte preconcentration; remove matrix interferents | Extraction of antimicrobials from serum samples [13] |

| UPLC/HPLC Columns (C18, HSS T3) | Analytical separation of compounds based on hydrophobicity | Waters ACQUITY UPLC HSS T3 for separation of phenolic acids and flavonoids [10] |

| Mass Spectrometry Grade Solvents | High purity mobile phase components; minimize background noise and contamination | LC-MS grade acetonitrile and formic acid for antimicrobial analysis [13] |

| Ion Pairing Reagents (Formic Acid, Ammonium Acetate) | Enhance ionization efficiency in MS; improve chromatographic peak shape | 0.1% formic acid in mobile phase for positive ion mode ESI [13] |

Methodological Workflows and Technological Relationships

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for validating biosensor results using chromatographic reference methods, highlighting the complementary nature of these technologies.

Biosensor Validation Workflow

The complementary relationship between emerging biosensor technologies and established chromatographic methods is further illustrated in the following diagram, which shows how these approaches serve different but interconnected roles in analytical science.

Analytical Technique Complementarity

Chromatographic methods, particularly LC-MS/MS and HPLC, maintain their position as gold standard techniques for quantitative analysis in pharmaceutical, clinical, and environmental applications. Their unparalleled specificity, sensitivity, and precision establish the necessary reference point for validating emerging biosensor technologies. While biosensors offer compelling advantages in speed, portability, and cost-effectiveness for rapid screening, they ultimately require correlation with chromatographic standards to verify analytical accuracy, especially in complex matrices. The future of bioanalysis lies not in the displacement of chromatography by biosensors, but in their strategic integration—utilizing biosensors for high-throughput preliminary screening and chromatographic methods for definitive confirmation and validation. This synergistic approach leverages the respective strengths of each technology, advancing analytical capabilities while maintaining the rigorous standards demanded by regulatory science and precision medicine.

Biosensors are compact analytical devices that transduce a biological response into a quantifiable signal, playing an increasingly vital role in environmental monitoring, point-of-care diagnostics, and drug development [14]. These devices leverage various biorecognition elements, including enzymes, antibodies, and nucleic acids, coupled with transducing elements such as electrochemical, optical, or piezoelectric systems to detect target analytes [14]. Despite their promise for portability and rapid analysis, biosensors face significant challenges in accuracy, specificity, and reproducibility that must be addressed through rigorous validation against established reference methods [7] [15] [6].

Liquid chromatography, particularly high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography (UPLC), represents the gold standard for analytical quantification in many fields. These methods provide high separation efficiency, sensitivity, and specificity through sophisticated physical separation of analytes prior to detection [16] [10]. The validation of biosensor performance against chromatographic methods is therefore critical for establishing analytical credibility, especially when biosensors are intended for deployment in field settings or point-of-care scenarios where conventional laboratory instrumentation is unavailable [7].

This guide objectively compares the performance characteristics of biosensor and chromatography platforms, providing researchers with experimental data and methodologies for conducting rigorous validation studies. By examining the strengths and limitations of each approach across multiple application domains, we aim to establish a framework for ensuring data reliability across analytical platforms.

Performance Comparison: Biosensors vs. Chromatographic Methods

Quantitative Performance Metrics

The table below summarizes key performance characteristics of biosensor and chromatographic methods based on experimental data from comparative studies:

Table 1: Performance comparison between biosensor and chromatographic methods

| Performance Characteristic | Biosensor Methods | Chromatographic Methods | Comparative Experimental Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Detection Limit | Varies by platform: Enzymatic biosensors detected organophosphorus pesticides at 0.1-5.7 μg/L [7] | Generally superior: UPLC-MS methods achieved LOD of 0.005-0.56 μg/mL for traditional Chinese medicine compounds [10] | Biosensors provided adequate detection for screening but generally higher LOD than chromatographic methods |

| Analysis Time | Minutes to <1 hour with potential for significant reduction using initial transient response [6] | Typically 10-30 minutes per sample, with complex separations requiring longer [16] | Biosensors demonstrated 3-5x faster analysis, with AI-guided approaches reducing time delay using early dynamic response [6] |

| Reproducibility | Meeting point-of-care standards requires optimized manufacturing and immobilization techniques [15] | High reproducibility with RSD typically <5% for retention time and peak area [10] | Semiconductor-manufactured biosensors with streptavidin biomediators showed highest reproducibility approaching chromatographic standards [15] |

| Multiplexing Capability | Strong potential for simultaneous detection of multiple analytes [14] | Limited to number of separable compounds with distinct retention times [16] | Biosensors demonstrated distinction between 3.9 and 10.3 μg/L of total target pesticides in water samples [7] |

| Specificity | High with optimized biorecognition elements; may cross-react with structurally similar compounds [14] [17] | Excellent with proper method development; diode-array detection provides spectral confirmation [7] [16] | Chromatography provided unequivocal confirmation of metabolites via UV spectra; biosensors showed positive indication of target class [7] |

Application-Specific Performance

The relative performance of these analytical platforms varies significantly across application domains, as evidenced by the following experimental findings:

Table 2: Application-specific performance comparison

| Application Domain | Biosensor Performance | Chromatography Performance | Validation Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pesticide Monitoring (Environmental) | Enzymatic biosensor based on acetylthiocholine chloride reaction detected organophosphorus pesticides and carbaryl at 0.1-5.7 μg/L [7] | Liquid chromatography with diode-array detection provided unequivocal confirmation of various oxometabolites from UV spectra [7] | Biosensor signals correlated with chromatographic results (r = 0.89); suitable for screening with confirmation by chromatography [7] |

| Infectious Disease Diagnostics | Broad-spectrum biosensors using conserved-site PCR identified diverse microorganisms; potential for point-of-care use [17] | LC-MS/MS methods provide definitive quantification but require complex sample preparation and longer analysis time [17] | Biosensors showed 92-98% concordance with culture methods for common pathogens; limitations with complex microbiota [17] |

| Traditional Medicine Analysis | SPR biosensors measured TNF-α binding affinity (KD = 1.38 × 10−6 M for 3-CQA) [10] | UPLC-PDA and UPLC-QDa methods validated with excellent linearity (R² > 0.9991) and recovery (98.78-105.13%) [10] | SPR enabled rapid binding assessment; UPLC provided comprehensive quantification of multiple active compounds [10] |

| MicroRNA Detection | Cantilever biosensors detected let-7a from nM to fM range; AI-guided classification achieved 98.5% accuracy [6] | HPLC with fluorescence detection typically limited to nM range without pre-concentration | Biosensors showed superior sensitivity for low-abundance nucleic acids; chromatography provided better quantification at higher concentrations |

Experimental Protocols for Method Validation

Side-by-Side Comparison Protocol

To validate biosensor performance against chromatographic reference methods, researchers should implement the following experimental protocol adapted from pesticide monitoring studies [7]:

Sample Preparation:

- Prepare calibration standards spanning the expected concentration range (e.g., 0.1-100 μg/L for environmental contaminants)

- Include both pure analyte solutions and spiked real-world matrices (serum, water, soil extracts) to assess matrix effects

- For biosensors requiring specific buffer conditions, ensure compatibility with chromatographic analysis through buffer exchange when necessary

Instrumental Analysis:

- Analyze all samples using the biosensor platform in triplicate, recording both steady-state signals and dynamic response trajectories

- Immediately analyze the same samples using the chromatographic reference method

- For HPLC/UPLC: Utilize optimized separation conditions (column temperature: 25-40°C, mobile phase: gradient elution with 0.1% formic acid in water/acetonitrile, flow rate: 0.2-0.6 mL/min) [16] [10]

- Employ appropriate detection methods (UV-Vis, MS, fluorescence) based on analyte characteristics

Data Analysis:

- Plot biosensor response versus chromatographic quantification to establish correlation coefficients

- Calculate key validation parameters: limit of detection (LOD), limit of quantification (LOQ), linearity, precision, and accuracy

- Perform statistical analysis (t-tests, F-tests) to determine significant differences between methods

Biosensor-Calibration Protocol Using Chromatography

For validating biosensors intended for field deployment, the following protocol establishes traceability to chromatographic reference methods [7]:

- Initial Calibration: Use chromatographically quantified standards to calibrate biosensor response across the operational range

- Matrix Testing: Evaluate biosensor performance in real sample matrices (water, blood, food extracts) with confirmation by chromatography

- Stability Assessment: Monitor biosensor performance drift over time using periodic validation with chromatographic analysis

- Cross-Validation: For quantitative biosensors, analyze identical samples using both methods and compute Pearson correlation coefficients

The experimental workflow for method validation illustrates the parallel analysis and correlation assessment required for rigorous biosensor validation.

Advanced Validation Approaches

Theory-Guided Deep Learning for Enhanced Biosensor Accuracy

Recent advances in artificial intelligence have enabled significant improvements in biosensor performance through theory-guided deep learning approaches [6]. The implementation protocol includes:

Data Acquisition and Augmentation:

- Collect dynamic biosensor response curves across multiple analyte concentrations

- Apply data augmentation to address sparsity and class imbalance in calibration data

- Generate synthetic response curves through mathematical modeling of binding kinetics

Model Development:

- Implement recurrent neural networks (RNN) for time-series classification of biosensor responses

- Incorporate domain knowledge through cost function supervision based on biosensor theory

- Train models to predict analyte concentration from initial transient response to reduce time delay

Validation:

- Compare theory-guided RNN (TGRNN) classification against conventional data analysis methods

- Assess performance metrics (F1 score, precision, recall) with and without theory guidance

- Validate model predictions against chromatographic quantification

Experimental results demonstrate that theory-guided deep learning improves F1 scores, precision, and recall by an average of 13.8%, enabling quantification of target analyte concentration with 98.5% accuracy using initial transient biosensor response [6].

Fragment Screening Validation Using SPR Biosensors

Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) biosensors have emerged as powerful tools for fragment-based drug discovery, with specific validation protocols [18]:

- Library Design: Select 930 compounds from commercially available sources using physicochemical and medicinal chemistry filters

- Multi-Target Screening: Screen fragments against three prototypical drug targets (HIV-1 protease, thrombin, carbonic anhydrase) and one non-target (human serum albumin)

- Promiscuity Assessment: Identify and eliminate compounds with non-specific binding (stoichiometry ≥5:1 with all proteins)

- Kinetic Analysis: Characterize binding kinetics, focusing on slow-dissociating compounds that may indicate problematic binders

This approach confirmed that 35-97% of fragments showed detectable interactions depending on the target protein, with only 0.2% demonstrating promiscuous binding behavior [18].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful validation studies require carefully selected reagents and materials. The following table details key solutions used in biosensor-chromatography correlation studies:

Table 3: Essential research reagents for validation studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Examples | Selection Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biorecognition Elements | Target capture and signal generation | Enzymes (acetylcholinesterase for pesticides), antibodies, nucleic acid probes [7] [14] | Specificity, stability, compatibility with immobilization method |

| Chromatography Columns | Analyte separation | HSS T3, BEH C18, Thermo Hypersil GOLD [10] | Separation efficiency, chemical stability, particle size (1.8 μm for UPLC) |

| Signal Labels | Detection and quantification | Metallic nanoparticles (gold, silver), fluorescent tags, enzymes [14] | High signal-to-noise, minimal non-specific binding, stability |

| Membranes | Fluidics and immobilization support | Nitrocellulose, PVDF with controlled pore size (5-15 μm) and protein holding capacity [14] | Wicking rate, protein binding capacity, uniformity, background signal |

| Mobile Phase Additives | Improve separation and peak shape | Triethylamine, formic acid, ammonium buffers [16] [19] | Peak symmetry enhancement, MS-compatibility, volatility |

| Immobilization Chemistries | Surface functionalization | NHS-EDC amine coupling, streptavidin-biotin systems, thiol-gold chemistry [15] [10] | Orientation control, binding capacity, stability under flow conditions |

Relationship between validation components and performance outcomes illustrates how proper reagent selection and methodology influence key biosensor performance metrics.

Validation remains a critical requirement for establishing the credibility of biosensor technologies, particularly as they transition from laboratory curiosities to field-deployable analytical tools. The experimental data and methodologies presented in this comparison guide demonstrate that while biosensors offer significant advantages in speed, portability, and potential for point-of-use testing, they generally require correlation with established chromatographic methods to verify accuracy and reliability.

Successful validation strategies incorporate multiple approaches: side-by-side comparison studies using identical samples, theory-guided data analysis to enhance biosensor performance, and rigorous statistical assessment of correlation coefficients and method agreement. Furthermore, the selection of appropriate research reagents—from biorecognition elements to separation materials—profoundly impacts the success of these validation efforts.

As biosensor technologies continue to evolve, incorporating advanced signal processing, artificial intelligence, and novel sensing modalities, the need for rigorous validation against reference methods will remain paramount. By adopting the comprehensive validation framework outlined in this guide, researchers can ensure that biosensor data meets the stringent requirements for scientific research, clinical decision-making, and regulatory compliance.

The validation of biosensor results against established chromatography methods represents a critical frontier in analytical science, particularly for pharmaceutical and clinical applications. As the demand for rapid, on-site testing grows, portable biosensors have emerged as powerful alternatives to traditional laboratory-bound techniques. This guide provides an objective comparison of these technologies, framing their performance characteristics within the rigorous context of analytical method validation. The core trade-off between the operational advantages of biosensors and the definitive accuracy of chromatographic methods is a fundamental consideration for researchers and drug development professionals designing analytical strategies. This comparison is grounded in experimental data and validation protocols, offering a practical framework for technology selection and method development.

Portable biosensors are analytical devices that integrate a biological recognition element with a physicochemical transducer to produce a measurable signal [20]. Their design is inherently geared toward speed, portability, and ease of use, making them ideal for point-of-care diagnostics, environmental monitoring, and rapid screening [21] [22]. In contrast, chromatographic methods, such as Gas Chromatography (GC) and High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC), are separation-based techniques that serve as the gold standard for ultimate accuracy, specificity, and precision in quantitative analysis [23]. They are typically laboratory-based, requiring sophisticated instrumentation and skilled operators.

The primary trade-off between these technologies is encapsulated in their core design philosophies. Biosensors sacrifice a degree of analytical rigor for operational advantages, while chromatography prioritizes definitive quantification at the cost of speed and accessibility. This relationship is not merely competitive but often complementary; biosensors are frequently validated and calibrated using chromatographic data as a reference [24]. Understanding this balance is essential for deploying the right tool for the right application, whether for rapid field screening or definitive regulatory analysis.

Table 1: Core Characteristics and Typical Applications

| Feature | Portable Biosensors | Chromatography Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Strength | Speed, portability, on-site capability | Ultimate accuracy, specificity, and precision |

| Typical Analysis Time | Minutes to a few hours [21] [20] | Hours to days (including sample prep) |

| Portability | High; handheld and smartphone-integrated systems exist [21] | Low; confined to laboratory settings |

| Sample Throughput | Potential for high-throughput with multiplexing [21] | Generally low to medium |

| Operator Skill Required | Low to moderate | High |

| Ideal Application | Rapid disease diagnosis, on-site contaminant screening, therapeutic drug monitoring [21] [20] [22] | Drug quality control, regulatory compliance, pharmacokinetic studies [23] |

Comparative Performance Data

When evaluated against standard validation parameters, the performance disparities and convergences between biosensors and chromatography become clear. The following tables summarize quantitative data and validation benchmarks for both technologies.

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Experimental data from recent studies demonstrates that biosensors can achieve impressive sensitivity, often detecting analytes at nanomolar to femtomolar concentrations [6] [20]. For instance, a portable aptamer-based biosensor detected platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) with a limit of detection (LOD) of 2.9 fM [20]. However, their precision, often measured by Relative Standard Deviation (RSD), can be more variable than chromatographic methods.

Table 2: Comparison of Experimental Performance Data

| Analyte | Technology | Limit of Detection (LOD) | Precision (RSD) | Dynamic Range | Analysis Time | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MicroRNA (let-7a) | Cantilever Biosensor with AI | Femtomolar (fM) range | Precision of 98.5% (with AI guidance) [6] | nM to fM | Rapid (using initial transient response) [6] | [6] |

| Lactate | Electrochemical Biosensor (Screen-printed electrode) | 0.01 mM | Not Specified | 0.025–0.25 mM | < 60 seconds [20] | [20] |

| Cortisol | Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) Biosensor | 1.0 ng/mL | Not Specified | 1.5 ng/mL – 10 ng/mL | < 10 minutes [20] | [20] |

| Residual Solvents | Gas Chromatography (GC) | Determined by S/N (e.g., 3:1) [23] | RSD < 2% (Repeatability), RSD < 3% (Intermediate Precision) [23] | LOQ to 120% of working level | Typically 30+ minutes | [23] |

| Pharmaceutical Compounds | HPLC / GC | Determined by S/N [25] | Adheres to strict validation guidelines (e.g., ICH) [25] | Validated linear range [25] | Typically 30+ minutes | [25] |

Validation Parameter Benchmarks

The validation of any analytical method relies on a set of defined performance characteristics. Chromatography methods are validated against stringent, internationally recognized criteria [25] [23]. Biosensor validation, while following the same principles, often shows different performance profiles.

Table 3: Validation Benchmarks: Biosensors vs. Chromatography

| Validation Parameter | Portable Biosensors (Typical Performance) | Chromatography Methods (Acceptance Criteria) | Key Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | Varies; can be high but susceptible to matrix effects [24]. Often demonstrated via recovery studies. | Recovery typically within 98-102% [23]. | Chromatography provides definitive quantification; biosensors may require extensive calibration. |

| Precision | Can be enhanced with advanced data processing (e.g., AI) to >98% [6]. | RSD < 2% (repeatability); RSD < 3% (intermediate precision) [23]. | Chromatography offers superior reproducibility, a critical factor for regulatory submission. |

| Specificity | High, due to specific biorecognition (enzymes, antibodies, aptamers) [21] [26]. Can be compromised by cross-reactivity. | No interference with analyte peaks; confirmed via peak purity tests (e.g., PDA, MS) [25]. | Chromatography with MS detection provides unmatched specificity for complex samples. |

| Linearity | Demonstrated over a defined concentration range relevant to the application [20]. | Correlation coefficient (r) ≥ 0.999 across the specified range [23]. | Chromatography is validated for a wide, defined linear range, essential for quantitative work. |

| LOD/LOQ | Extremely low (fM) possible [6] [20]. Often based on S/N or statistical methods. | LOD (S/N ≈ 3:1), LOQ (S/N ≈ 10:1) [25] [23]. | Both can be highly sensitive, but biosensors achieve this in a direct, label-free manner. |

| Robustness | An ongoing challenge; performance can be affected by environmental conditions, sample matrix, and bioreagent stability [21] [27]. | Consistent performance under deliberate, minor variations in method parameters [23]. | Chromatography is a mature, highly robust technology, whereas biosensor robustness is a key R&D focus. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To illustrate how performance data is generated and validated, below are detailed protocols for a key biosensor experiment and a standard chromatography validation procedure.

Protocol 1: Validating Biosensor Kinetics Using a Theory-Guided Deep Learning Approach

This protocol, adapted from Zhang et al., describes a method to enhance the accuracy and speed of a cantilever biosensor for microRNA detection using dynamic signal analysis, providing a robust framework for biosensor validation [6].

1. Biosensor Functionalization:

- Immobilization: Continuously flow a 3 μM solution of thiolated-DNA probe (e.g., HS–C6-5′ TTTTTTAACTATACAAC 3′) over a gold-coated cantilever sensor surface in a custom flow cell. This forms a self-assembled monolayer (SAM) as the biorecognition element [6].

- Blocking: After probe immobilization, flow a blocking solution (e.g., 6-mercapto-1-hexanol) to passivate unreacted gold surfaces and minimize non-specific binding.

2. Sample Preparation and Data Acquisition:

- Standard Solutions: Prepare a series of standard solutions of the target analyte (e.g., microRNA let-7a) across the desired concentration range (e.g., nanomolar to femtomolar).

- Data Collection: For each standard solution, perfuse the sample over the functionalized biosensor chip and record the dynamic response (e.g., resonant frequency shift, Δf, vs. time). This generates a sensorgram for each concentration [6] [24].

3. Data Preprocessing and Augmentation:

- Address Data Sparsity: To overcome limitations of small calibration datasets, employ data augmentation techniques. This involves creating synthetic data points from the existing experimental sensorgrams to improve the robustness of subsequent deep learning models [6].

- Categorical Structuring: Format the data for classification by treating each target analyte concentration level as a distinct category.

4. Theory-Guided Deep Learning (TGRNN) Analysis:

- Model Training: Train a Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) classifier to identify the target concentration category based on the dynamic biosensor response.

- Cost Function Supervision: Guide the RNN training by incorporating domain knowledge. This is done by adding a cost function that penalizes predictions inconsistent with the established theory of surface-based biosensor kinetics, ensuring explainable and physically plausible results [6].

- Performance Evaluation: Validate the TGRNN model using hold-out data. Metrics such as F1 score, precision, and recall are calculated, with modern studies achieving averages of 98.5% [6].

5. Validation and Cross-Checking:

- Concentration Prediction: Use the trained TGRNN model to predict the concentration of unknown samples from their dynamic sensor response.

- Independent Verification: Where possible, cross-validate biosensor results against a reference method, such as liquid chromatography, for critical applications [24].

Biosensor AI Validation Workflow

Protocol 2: GC Method Validation for Ultimate Accuracy

This protocol outlines the standard steps for validating a Gas Chromatography (GC) method, as defined by regulatory bodies like ICH and FDA, establishing the benchmark for analytical accuracy [25] [23].

1. Method Development and Optimization:

- Define and optimize all critical GC parameters: inlet temperature, detector temperature, oven temperature ramp, carrier gas type and flow rate, and column selection [23].

2. Specificity Testing:

- Procedure: Inject the target analyte standard, a blank sample (matrix without analyte), and a sample spiked with potential interferents.

- Acceptance Criterion: The analyte peak must be resolved from all other peaks with no interference, confirmed by comparing retention times and, ideally, using a peak purity test (e.g., Photodiode Array or Mass Spectrometry detection) [25] [23].

3. Linearity and Range Determination:

- Procedure: Prepare and analyze a minimum of 5 standard solutions covering the range from the LOQ to 120% of the expected sample concentration.

- Acceptance Criterion: The calibration curve must have a correlation coefficient (r) of ≥ 0.999 [23].

4. Limit of Detection (LOD) and Quantitation (LOQ) Determination:

- Procedure: Analyze progressively diluted standards and measure the signal-to-noise (S/N) ratio.

- Acceptance Criterion: LOD is typically defined as S/N ≥ 3:1, and LOQ as S/N ≥ 10:1. Alternatively, based on the standard deviation of the response and the slope of the calibration curve (LOD = 3.3σ/S, LOQ = 10σ/S) [25] [23].

5. Accuracy Evaluation via Recovery Study:

- Procedure: Spike the sample matrix with known quantities of the analyte at multiple levels (e.g., 80%, 100%, 120% of target). Calculate the percentage recovery of the measured value versus the known added amount.

- Acceptance Criterion: Recovery is typically within 98-102% [23].

6. Precision Assessment:

- Repeatability (Intra-assay): Perform multiple injections (n=6 or more) of a homogeneous sample on the same day by the same analyst using the same instrument.

- Intermediate Precision (Ruggedness): Have a second analyst repeat the analysis on a different day using a different instrument in the same laboratory.

- Acceptance Criterion: RSD for repeatability is typically < 2%; for intermediate precision, RSD < 3% [25] [23].

7. Robustness Testing:

- Procedure: Deliberately introduce small, deliberate variations in method parameters (e.g., carrier gas flow rate ±0.1 mL/min, oven temperature ±1°C).

- Acceptance Criterion: The method's performance (e.g., resolution, tailing factor) must remain consistent and within specified limits under all varied conditions [23].

GC Method Validation Protocol

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The performance of both biosensors and chromatography is heavily dependent on the quality and specificity of the reagents and materials used. The following table details essential components for developing and validating these analytical platforms.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Biorecognition Elements (Antibodies, DNA probes, Aptamers, Enzymes) | Provides specificity by binding the target analyte. The choice of element directly impacts sensitivity and cross-reactivity. | Core to all biosensors. Aptamers, selected via SELEX, are popular for small molecules and toxins [21] [26]. |

| Surface Functionalization Reagents (e.g., Thiolated probes for gold surfaces, SAMs like 4-ATP, cross-linkers like Glutaraldehyde) | Enables stable immobilization of the biorecognition element onto the transducer surface, which is critical for assay reproducibility and minimizing noise. | Essential for surface-based biosensors (e.g., SPR, cantilevers, electrochemical) [21] [6] [28]. |

| High-Accuracy Standard Solutions | Used for instrument calibration and method validation. Their purity and traceability are fundamental for establishing accuracy and meeting regulatory standards. | Critical for chromatography method development and validation [23]. Also used as reference materials to calibrate and validate biosensors [24]. |

| Nanomaterials (Graphene, MXenes, Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs), Quantum Dots) | Enhance sensor performance by increasing surface area, improving electron transfer, and enabling signal amplification. This boosts sensitivity and can lower LOD. | Used to modify electrodes in electrochemical biosensors [28] or as labels in optical biosensors [21]. |

| Microfluidic Cartridges/Chips | Miniaturize and automate fluid handling, reducing sample and reagent volumes, improving assay speed, and enabling the integration of multiple processing steps. | Key for developing commercial, user-friendly, and disposable portable biosensors [27] [26]. |

| Chromatographic Columns and Phases | The heart of the separation process. The stationary phase chemistry dictates the selectivity and resolution of the analytes. | Core component of all GC and HPLC systems. Selection is analyte-dependent [23]. |

Integrated Data Analysis and Signaling Pathways

The final stage of analysis in both biosensors and chromatography involves interpreting complex data. For biosensors, this increasingly involves advanced computational tools to extract accurate information from dynamic signals.

Advanced Data Analysis for Complex Biosensor Data

A major challenge in biosensing is the reliable analysis of kinetic binding data, especially when interactions are complex and far from steady-state. A four-step strategy using the Adaptive Interaction Distribution Algorithm (AIDA) has been developed for this purpose [24]:

- Dissociation Graph Analysis: Plot ln[R(t)/R₀] against time for the dissociation phase. A non-linear, convex curve indicates heterogeneity (i.e., more than one type of analyte-ligand interaction) [24].

- Rate Constant Distribution (RCD) with AIDA: The AIDA algorithm is applied to the sensorgram data to calculate a distribution of possible association (kₐ) and dissociation (k_d) rate constants. This fast numerical tool identifies the number of distinct interactions without pre-selecting a model [24].

- Rate Constant Estimation: The peaks in the RCD plot provide initial estimates for the rate constants of each interaction type. These estimates are then used as inputs for a more precise fitting of the sensorgram data [24].

- Clustering and Validation: All estimated rate constants from multiple sensorgrams are plotted and clustered. Each cluster represents a distinct complex formation reaction, providing a robust and data-driven model of the system's interactions [24].

This methodology is more robust than standard global fitting to a simple 1:1 model, as it can reveal complex binding kinetics and handle system drift, leading to more reliable results [24].

A Step-by-Step Methodology for Correlating Biosensor and Chromatography Data

The increasing integration of biosensors in pharmaceutical research and environmental monitoring demands rigorous validation to ensure data reliability and regulatory compliance. Effective validation establishes that a biosensor is suitable for its intended purpose, providing confidence in its analytical results. This guide details the core components of a robust validation study, focusing on sample preparation, parallel testing against established methods like chromatography, and systematic data collection. The objective is to provide a clear framework for generating high-quality, comparable data that can objectively demonstrate biosensor performance against reference standards.

A typical biosensor consists of a biological recognition element (e.g., antibodies, enzymes, DNA) linked to a substrate and integrated with a transducer that converts a biological interaction into a measurable signal [29]. The validation of these devices is critical, as the number of publications featuring biosensor data has nearly doubled since 2009, yet critical methodological information is often poorly described, making replication difficult [30]. This guide, framed within the broader context of validating biosensor results against chromatography methods, provides actionable protocols for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Core Validation Study Design

Key Validation Parameters

A comprehensive validation study must evaluate several key analytical performance parameters. These parameters collectively define the operational boundaries and reliability of the biosensor for a specific application.

Table 1: Key Analytical Parameters for Biosensor Validation

| Parameter | Definition | Acceptance Criteria Example |

|---|---|---|

| Specificity | The ability to detect the target analyte in the presence of other components. | No significant cross-reactivity with similar compounds [31]. |

| Accuracy | The closeness of agreement between the biosensor value and an accepted reference value. | Recovery rates between 80-120% [32]. |

| Precision | The closeness of agreement between a series of measurements. | Intraday repeatability RSD < 1.5%; between-day precision RSD < 5% [32]. |

| Linearity | The ability to obtain results directly proportional to analyte concentration. | R² value ≥ 0.975 [33]. |

| Limit of Detection (LOD) | The lowest amount of analyte that can be detected. | Statistically determined signal-to-noise ratio (e.g., 3:1). |

| Limit of Quantification (LOQ) | The lowest amount of analyte that can be quantified with acceptable accuracy and precision. | Statistically determined signal-to-noise ratio (e.g., 10:1). |

| Robustness | A measure of capacity to remain unaffected by small, deliberate variations in method parameters. | Consistent performance across pH, temperature, or operator changes [33]. |

The Role of Sample Preparation

Sample preparation is a critical first step that can significantly impact the outcome of a validation study. Inconsistent or improper sample handling introduces variability before analysis even begins [34]. The overarching goal is to present the analyte in a form compatible with both the biosensor and the reference chromatography method, while minimizing interference.

Automation is increasingly used to enhance the reliability of this stage. Automated sample preparation systems can perform tasks such as dilution, filtration, solid-phase extraction (SPE), and derivatization, thereby reducing human error and improving consistency, especially in high-throughput environments [34]. For instance, standardized, ready-made kits for sample cleanup (e.g., for PFAS analysis or oligonucleotide extraction) provide optimized protocols that ensure accurate and reproducible results when moving to LC-MS analysis [34].

Table 2: Common Sample Types and Preparation Considerations

| Sample Matrix | Common Preparation Steps | Potential Interferences |

|---|---|---|

| Serum/Blood | Dilution, filtration, protein precipitation. | Lipids, proteins, endogenous biomarkers. |

| Water/Environmental | Filtration, pH adjustment, concentration (e.g., SPE). | Dissolved organic matter, particulate matter, other contaminants. |

| Food Products | Homogenization, extraction with solvent, cleanup. | Fats, carbohydrates, pigments. |

| Bacterial Cultures | Centrifugation, lysis, dilution. | Cellular debris, growth media components. |

Experimental Protocols for Parallel Testing

Protocol for Validating a Heavy Metal GEM Biosensor

This protocol is adapted from the validation of a Genetically Engineered Microbial (GEM) biosensor for detecting Cd²⁺, Zn²⁺, and Pb²⁺ [33].

Biosensor Cultivation and Preparation:

- Inoculate the GEM biosensor (e.g., E.coli-BL21:pJET1.2-CadA/CadR-eGFP) in a suitable growth medium.

- Incubate at 37°C with shaking until the culture reaches the mid-logarithmic growth phase.

- Dilute the bacterial cells to a standardized optical density (e.g., OD600 = 0.5) using fresh medium.

Sample Preparation and Treatment:

- Prepare stock solutions (e.g., 100 ppm) of the target analytes (Cd²⁺, Zn²⁺, Pb²⁺) and potential interfering ions (Ni²⁺, Fe³⁺, AsO₄³⁻) from certified reference materials.

- Spike the standardized biosensor culture with a series of known concentrations of the target analytes (e.g., 0.1 to 5.0 ppm). Include a negative control (no metal added) and a positive control if available.

- Incubate the treated cultures under optimal physiological conditions (e.g., 37°C, pH 7.0) for a predetermined period to allow for reporter gene expression.

Biosensor Signal Measurement:

- Measure the fluorescent signal (e.g., eGFP emission) using a fluorometer, microplate reader, or fluorescence microscopy.

- For quantitative analysis, calibrate the fluorescent intensity against the heavy metal concentration to generate a standard curve.

Parallel Analysis with Reference Method:

- Digest an aliquot of the same prepared samples with strong acids following conventional procedures for heavy metal analysis.

- Analyze the digested samples using a reference chromatographic or spectrometric method, such as Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) or Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS).

- Confirm the actual concentration of metals in the samples using the reference method.

Data Comparison and Analysis:

- Plot the biosensor response (fluorescence intensity) against the reference method concentration values.

- Calculate key validation parameters: linearity (R²), limit of detection (LOD), limit of quantification (LOQ), and accuracy (recovery %).

Diagram 1: GEM Biosensor vs Reference Method Workflow

Protocol for Validating an Immunochromatographic Biosensor

This protocol is based on the development of a colloidal gold-based biosensor for quantifying S100B in serum [31].

Biosensor Strip Assembly and Principle:

- The biosensor utilizes a double-antibody sandwich format. A monoclonal antibody (e.g., 8C10) is conjugated to colloidal gold nanoparticles (the detector).

- A second monoclonal antibody (e.g., 6B8) is immobilized on the nitrocellulose membrane as the capture antibody at the test line (T-line). A control antibody is immobilized at the control line (C-line).

Sample Preparation and Application:

- Obtain or prepare clinical serum samples. Minimal dilution may be required.

- Apply a precise volume (e.g., 70-100 µL) of the serum sample to the sample pad of the biosensor strip.

- The sample migrates via capillary action, rehydrating the gold-conjugated antibodies.

Biosensor Signal Acquisition:

- Allow the test to develop for a fixed time (e.g., 15 minutes).

- Insert the strip into a dedicated optical reader that scans the intensity of the T-line and C-line.

- The reader calculates the T/C value (ratio of test line signal to control line signal), which is proportional to the analyte concentration.

Parallel Analysis with Reference Method:

- Analyze the same set of clinical serum samples using a validated reference immunoassay, such as a Chemiluminescence Immunoassay (CLIA) or Electrochemiluminescence Assay (ECLIA).

- Ensure the reference method is performed according to its standardized protocol.

Data Comparison and Analysis:

- Construct a calibration curve for the biosensor by plotting the T/C values against known concentrations of a purified S100B standard.

- Compare the quantitative results (S100B concentration) obtained from the biosensor and the reference method for all clinical samples (e.g., n=40).

- Perform correlation analysis (e.g., Pearson's correlation coefficient) and assess the agreement between the two methods using Bland-Altman analysis.

Data Collection, Analysis, and Reporting Standards

Structured Data Collection and Comparison

Data collection must be systematic to facilitate a direct and unbiased comparison. The following table provides a template for organizing primary data when comparing a biosensor to a reference chromatography method.

Table 3: Template for Parallel Testing Data Collection

| Sample ID | Theoretical Concentration | Biosensor Response (Raw) | Biosensor Calculated Concentration | Reference Method Concentration | Recovery (%) | Deviation (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calibrator 1 | 0.1 ng/mL | 15.5 (T/C) | 0.095 ng/mL | 0.098 ng/mL | 96.9% | -3.1% |

| Calibrator 2 | 1.0 ng/mL | 85.2 (T/C) | 1.02 ng/mL | 1.05 ng/mL | 97.1% | -2.9% |

| Patient Serum A | Unknown | 45.1 (T/C) | 0.48 ng/mL | 0.50 ng/mL | 96.0% | -4.0% |

| Patient Serum B | Unknown | 120.5 (T/C) | 1.45 ng/mL | 1.40 ng/mL | 103.6% | 3.6% |

Essential Reporting Standards (STROBE)

To ensure reproducibility and transparency, the scientific community is moving towards standardized reporting. The Standards for Reporting Optical Biosensor Experiments (STROBE) guideline is a key initiative in this direction [30]. When publishing validation data, the following must be clearly reported:

- Sample Preparation: Detailed description of the sample matrix, all processing steps, reagents, and storage conditions.

- Biosensor Description: Exact type of biosensor, biological recognition element, transducer principle, and instrument model.

- Method Settings: All critical instrument parameters (e.g., temperature, flow rates, gain settings, acquisition time).

- Data Evaluation: Software used, data processing steps, fitting models for calibration curves, and statistical methods for comparison.

- Reference Method: Full details of the reference chromatography or other method used for comparison, including any sample preparation specific to it.

The Scientist's Toolkit

A successful validation study relies on specific reagents and materials. The following table details key solutions used in the featured experiments.

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Biosensor Validation

| Reagent / Material | Function in Validation | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Monoclonal Antibody Pairs | Serve as the capture and detection elements in immunosensors, defining specificity. | Anti-S100B mAbs 8C10 and 6B8 for sandwich immunoassay [31]. |

| Colloidal Gold Nanoparticles | Act as a colorimetric label for detection in lateral flow biosensors, enabling visual and optical quantification. | Used as the detector conjugate in the S100B immunochromatographic biosensor [31]. |

| Genetically Engineered Circuit | The core sensing element in whole-cell biosensors, encoding the response to a specific analyte. | The CadA/CadR-eGFP gene circuit for heavy metal detection in E. coli [33]. |

| Certified Reference Materials | Provide a traceable standard for preparing known analyte concentrations for calibration and accuracy checks. | Certified heavy metal salts (CdCl₂, Pb(NO₃)₂) for GEM biosensor calibration [33]. |

| Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE) Kits | Purify and concentrate analytes from complex samples, reducing matrix effects before analysis. | Stacked cartridges for PFAS isolation in environmental samples prior to LC-MS [34]. |

Diagram 2: Validation Study Logical Flow

The validation of novel biosensors against established analytical techniques is a critical step in ensuring their reliability and adoption in research and industrial applications. This process is particularly critical in life sciences and drug development, where the accuracy of measurements can directly impact scientific conclusions and product quality. Fluorescent biosensors offer the potential for rapid, sensitive, and high-throughput analysis, but require rigorous benchmarking against gold-standard methods to verify their performance. High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) represents one such benchmark in the quantification of small molecules, prized for its robustness, sensitivity, and specificity. This case study examines the specific validation of a GFP-based fluorescent biosensor (Tre‑C04) for the quantification of trehalose in insect hemolymph, providing a template for the validation paradigms essential for accrediting new biosensor technologies within the broader context of analytical chemistry [35] [36].

The Tre-C04 Biosensor: Principle and Design

The Tre‑C04 biosensor is engineered for high-sensitivity detection of trehalose. Its core mechanism relies on a single fluorescent protein that integrates a trehalose-binding protein with a circularly permuted Green Fluorescent Protein (cpGFP) [35].

In the absence of trehalose, the cpGFP emits only weak fluorescence. When trehalose binds to the biosensor, it induces a conformational change that enhances the green fluorescence emission. The intensity of this fluorescence correlates directly with the concentration of trehalose, enabling quantitative measurements. This design allows for sensitive detection in minimal sample volumes, making it ideal for applications where material is scarce, such as single-insect analysis [35].

The following diagram illustrates the conformational change that occurs upon trehalose binding, which is the basis of the biosensor's signal generation.

Experimental Protocol for Method Comparison

A direct comparison was conducted to benchmark the performance of the Tre-C04 biosensor against a traditional HPLC method for quantifying trehalose in aphid hemolymph [35].

Biosensor Assay with Tre-C04

- Biosensor Purification: The Tre-C04 biosensor was expressed in E. coli BL21 (DE3) cells using the pTKEI-Tre-C04 plasmid. Expression was induced, and the recombinant protein was purified via Ni–NTA affinity chromatography [35].

- Sample Preparation: Hemolymph was collected from individual aphids and diluted with distilled water to ensure the trehalose concentration fell within the biosensor's dynamic range (below 1,000 nM) [35].

- Fluorescence Measurement: Diluted hemolymph samples were mixed with the purified Tre-C04 biosensor. Fluorescence was measured using a Qubit 3 Fluorometer. The trehalose concentration was calculated from a standard curve generated with a 50 nM trehalose calibration standard [35].

HPLC Reference Method

- Chromatography System: HPLC analysis was performed using an Aminex HPX-87C column, a specialized column for sugar separation [35].

- Sample Preparation: For HPLC, a larger volume of hemolymph (100 nL) was required. This volume typically necessitated pooling samples from at least 10 adult aphids to exceed the method's detection limit. The hemolymph was diluted in 80% ethanol containing 1% sorbitol as an internal standard, completely dried, and then reconstituted in distilled water for injection [35].

- Separation and Detection: The analysis relied on isocratic elution (a constant mobile phase composition) to separate trehalose from other components. Detection was based on the intrinsic properties of the sugar, without the need for derivatization, confirming trehalose as the dominant hemolymph sugar [35].

Critical Comparison of Analytical Performance

The side-by-side application of both methods to the same biological system allows for a clear comparison of their analytical performance and practical utility.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Tre-C04 Biosensor and HPLC for Trehalose Measurement in Aphid Hemolymph

| Parameter | Tre-C04 Fluorescent Biosensor | HPLC with Aminex HPX-87C Column |

|---|---|---|

| Measured Trehalose (A. pisum) | 227.3 ± 10.0 mM (mean ± SD) [35] | 218.9 ± 34.4 mM (mean ± SD) [35] |

| Detection Range | 183.5 - 261.7 mM (in individual adults) [35] | N/A (Pooled samples required) [35] |

| Sample Throughput | Rapid, suitable for high-throughput [35] | Slower, limited by run time and sample prep [35] |

| Sample Volume | Single-insect level (very small volume) [35] | ≥ 100 nL, requires pooling from ~10 insects [35] |