Wearable Biosensors for Continuous Health Monitoring: Technologies, Applications, and Future Frontiers in Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the current state and future trajectory of wearable biosensors for continuous health monitoring, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Wearable Biosensors for Continuous Health Monitoring: Technologies, Applications, and Future Frontiers in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the current state and future trajectory of wearable biosensors for continuous health monitoring, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles of biosensing technologies, including electrochemical, optical, and piezoelectric transducers, and their integration into flexible, miniaturized platforms. The scope extends to cutting-edge methodological applications, such as therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) and the management of chronic diseases, leveraging non-invasive sampling of biofluids like sweat, saliva, and tears. The review critically addresses persistent challenges in sensor accuracy, power efficiency, and data standardization, while evaluating validation frameworks and performance metrics essential for clinical adoption. By synthesizing insights from recent academic literature and market analyses, this article aims to serve as a foundational resource for innovators shaping the next generation of personalized and predictive healthcare tools.

The Foundation of Modern Biosensing: Core Principles and Technological Evolution

Wearable biosensors are defined as wearable sensing devices that incorporate a biological recognition element and a physico-chemical transducer to provide continuous, real-time physiological information via dynamic, non-invasive measurements of biomarkers in biofluids such as sweat, tears, saliva, and interstitial fluid [1]. These devices have revolutionized contemporary medical healthcare monitoring systems by decentralizing the concept of regular clinical check-ups towards more versatile, remote, and personalized healthcare [2]. The fundamental operational principle involves the highly specific recognition of a target analyte by a bioreceptor, followed by the transduction of this biorecognition event into a quantifiable signal that can be processed, analyzed, and communicated [1] [2]. This architecture enables the continuous monitoring of dynamic biochemical processes, providing invaluable insights into a wearer's health status, enhancing chronic disease management, and alerting users or medical professionals to abnormal physiological situations [1].

Fundamental Components of Wearable Biosensors

Biorecognition Elements

The biorecognition element is responsible for the selective recognition of the target analyte and is the foundation of biosensor specificity [1] [2]. These elements can include enzymes, antibodies, whole cells, aptamers, and molecularly imprinted polymers [2]. Recent developments have favored aptamers due to their high specificity and sensitivity, along with superior stability compared to protein-based receptors [2]. The immobilization strategy for these biorecognition elements on the sensor surface is critical for maintaining their bioactivity and orientation, directly impacting sensor performance, stability, and shelf life [2]. Physical adsorption, covalent bonding, encapsulation, and affinity-based immobilization represent common approaches, each with distinct advantages for specific applications and operational environments [2].

Transduction Mechanisms

The physico-chemical transducer converts the biological recognition event into a measurable signal [1]. The primary transduction mechanisms in wearable biosensors include:

- Electrochemical Transduction: Measures electrical signals generated by biochemical reactions, including amperometric (current), potentiometric (potential), and conductometric (conductivity) measurements [2]. These sensors benefit from simple setup, cost efficiency, robust detection limits, and high specificity [2].

- Optical Transduction: Utilizes light-matter interactions for detection, including colorimetric, fluorescence, and surface plasmon resonance techniques [1] [3]. Recent advances include nanozyme-based colorimetric detection that offers high sensitivity, stability, and adjustable catalytic activities [3].

- Mechanical Transduction: Relies on physical changes such as mass, force, or pressure variations, often measured through piezoresistive, capacitive, or piezoelectric effects [2].

Table 1: Comparison of Primary Transduction Mechanisms in Wearable Biosensors

| Transduction Mechanism | Measured Parameter | Advantages | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electrochemical | Current, potential, or impedance | High specificity, low cost, miniaturization capability | Glucose monitoring (e.g., Freestyle Libre [1]), lactate, electrolytes |

| Optical | Light intensity, wavelength, or phase | Visual readouts, multiplexing capability | Colorimetric glucose patches [3], sweat pH monitoring |

| Mechanical | Mass, pressure, or force | Direct physical measurement, high sensitivity | Pulse monitoring, pressure-sensitive insoles |

Advanced Materials and Fabrication Strategies

The development of advanced materials has been instrumental in enhancing the wearability and performance of biosensors. Flexibility and stretchability are essential requirements for wearable biosensors to ensure comfort and maintain consistent skin contact during movement [2]. Material innovations include:

- Polymer-based composites with embedded nanostructures that maintain electrical conductivity under mechanical deformation [4]

- Skin-inspired patterned meshes that adapt to the human body's curvilinear surface [2]

- Hydrogels, textiles, and paper-based substrates that provide flexible, stretchable, and breathable platforms [2]

These advanced materials enable the development of epidermal wearable biosensors that conform to skin topography while maintaining biosensing functionality, facilitating real-time analysis of biomarkers in epidermal biofluids such as sweat and interstitial fluid [1]. Recent demonstrations include polymer-based sensors that withstand over 1,000 cycles of mechanical deformation with minimal resistance drift (<3%), enabling robust continuous monitoring during daily activities [4].

Experimental Protocols for Wearable Biosensor Development

Protocol: Fabrication of Flexible Electrochemical Biosensor

This protocol outlines the fabrication of a flexible electrochemical biosensor for metabolite monitoring (e.g., glucose, lactate) in sweat [2] [4].

Materials Required:

- Flexible polymer substrate (e.g., PET, PI, or elastomeric material)

- Conductive inks (e.g., carbon, Ag/AgCl, or graphene-based)

- Biorecognition elements (e.g., glucose oxidase, lactate oxidase)

- Cross-linking agents (e.g., glutaraldehyde, BS³)

- Encapsulation material (e.g., silicone, polyurethane)

- Screen-printing or inkjet printing equipment

Procedure:

- Substrate Preparation: Clean the flexible substrate with sequential washes of ethanol and deionized water, then dry under nitrogen stream.

- Electrode Fabrication: Deposit working, reference, and counter electrodes using screen-printing or inkjet printing techniques.

- Thermal Curing: Cure the printed electrodes at appropriate temperature (typically 60-90°C) for 1-2 hours to ensure adhesion and stability.

- Bioreceptor Immobilization: Apply biorecognition element solution to working electrode, followed by cross-linking agent to covalently bind the biological element.

- Membrane Application: Apply protective membrane (e.g., Nafion) to minimize biofouling and interference.

- Encapsulation: Apply encapsulation material to all non-sensing areas to ensure mechanical stability and electrical insulation.

- Quality Control: Verify electrode functionality through cyclic voltammetry in standard solutions (e.g., potassium ferricyanide).

Validation: Perform calibration with standard solutions of target analyte across physiological range. Assess sensor-to-sensor reproducibility (target CV <5%), sensitivity, and limit of detection.

Protocol: Integration with Wireless Data Transmission

This protocol describes the integration of biosensing elements with wireless communication modules for real-time data transmission [4].

Materials Required:

- Fabricated biosensor platform

- Microcontroller unit (e.g., ARM Cortex-M series)

- Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) module

- Power source (e.g., flexible battery or energy harvesting system)

- Mobile device or custom receiver for data collection

Procedure:

- Signal Conditioning Circuit Design: Design and implement front-end electronics for signal amplification and filtering appropriate to the transducer type.

- Microcontroller Programming: Program microcontroller to coordinate sensor sampling, signal processing, and data transmission.

- BLE Integration: Interface BLE module with microcontroller for wireless communication.

- Power Management: Implement power-saving strategies (e.g., duty cycling) to extend operational lifetime.

- Data Logging Firmware: Develop firmware for temporary data storage and transmission protocols.

- Mobile Application: Develop companion mobile application for data visualization, storage, and remote transmission.

- System Validation: Test end-to-end system functionality, including packet loss (target <1% [4]), latency, and power consumption under realistic use conditions.

Signaling Pathways and System Architecture

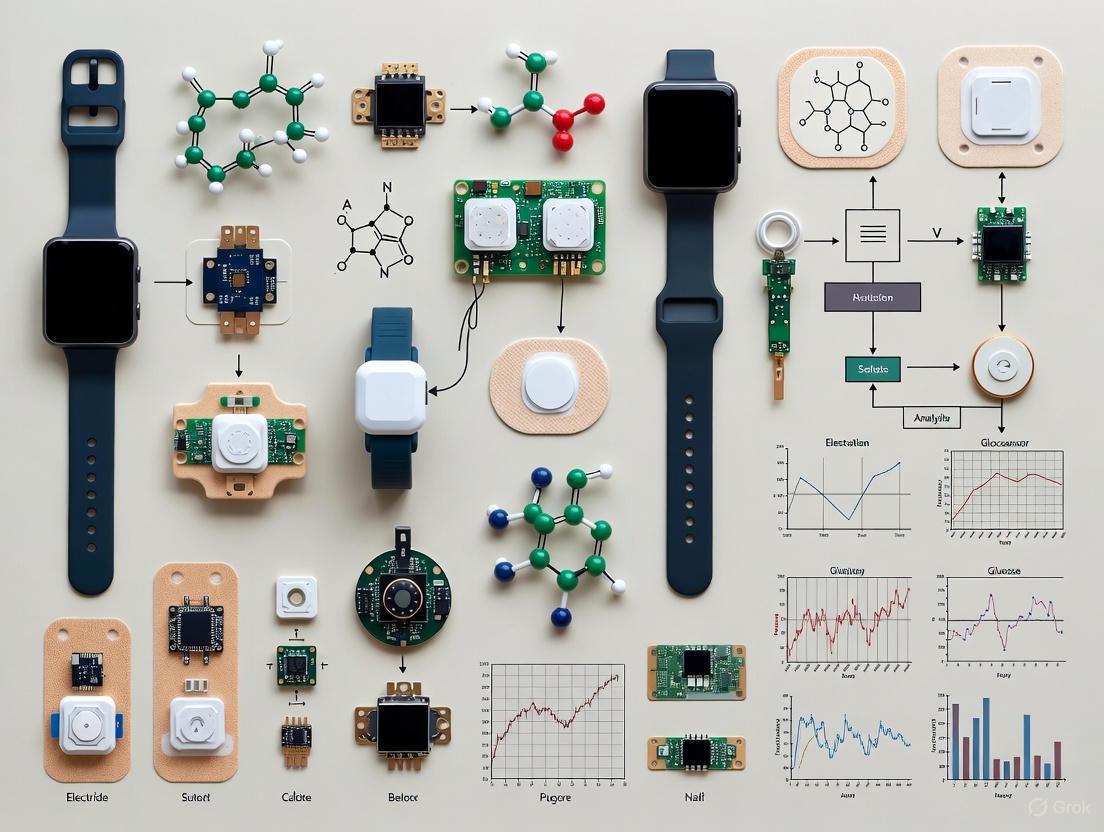

The following diagrams illustrate the fundamental architecture of wearable biosensors and the signal transduction pathways.

Diagram 1: Fundamental biosensor system architecture showing the pathway from analyte recognition to signal output.

Diagram 2: Classification of transduction mechanisms used in wearable biosensors.

Performance Metrics and Validation

Rigorous performance validation is essential for assessing wearable biosensor functionality and reliability. Key metrics include:

Table 2: Key Performance Metrics for Wearable Biosensor Evaluation

| Performance Parameter | Target Specification | Testing Methodology |

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | Sufficient to detect physiological analyte ranges | Calibration curve from standard solutions |

| Selectivity | >90% response to target vs. interferents | Interference testing with common biomarkers |

| Response Time | <60 seconds for real-time monitoring | Dynamic response measurement after analyte introduction |

| Operational Stability | <5% signal drift over 24 hours | Continuous operation in simulated biofluid |

| Mechanical Durability | <5% signal change after deformation | Performance testing during/after bending cycles |

| On-body Accuracy | MARD <10% vs. reference method | Clinical comparison study with gold standard |

Validation should progress from in-vitro testing in controlled laboratory conditions to in-vivo testing in realistic use environments [1] [2]. This includes assessing sensor performance during physical activity, environmental changes, and over extended wear periods. Additionally, correlation between analyte concentrations in non-invasive biofluids (e.g., sweat, tears) and blood levels must be established for clinical relevance [1] [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Wearable Biosensor Development

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Graphene & CNTs | Conductive nanomaterial with high surface area | Electrode modification for enhanced sensitivity [2] [4] |

| Molecularly Imprinted Polymers | Synthetic biorecognition elements | Stable alternative to biological receptors [2] |

| Nanozymes | Enzyme-mimicking nanomaterials | Colorimetric detection with enhanced stability [3] |

| Ionophores | Ion-selective recognition elements | Potentiometric sensing of electrolytes (Na+, K+) [2] |

| Cross-linking Agents | Bioreceptor immobilization | Covalent attachment to transducer surfaces [2] |

| Blocking Agents | Minimize non-specific binding | Improve selectivity in complex biofluids [2] |

| Hydrogel Matrix | Biofluid sampling and transport | Controlled analyte delivery to sensing interface [1] |

Emerging Trends and Future Perspectives

The field of wearable biosensors is rapidly evolving with several emerging trends shaping future developments:

Artificial Intelligence Integration: Machine learning and deep learning algorithms enhance real-time data processing, artifact rejection, and predictive analytics [5] [4] [6]. Recent demonstrations include hybrid CNN-LSTM architectures achieving 98.3% classification accuracy for physiological events [4].

Multimodal Sensing Systems: Integration of multiple sensing modalities within a single platform for comprehensive health assessment [7] [6]. These systems simultaneously monitor chemical biomarkers (e.g., glucose, lactate) and physical parameters (e.g., heart rate, activity).

Advanced Material Innovations: Development of self-healing materials, biodegradable substrates, and nanocomposites that enhance sensor longevity, sustainability, and biocompatibility [6].

Closed-Loop Therapeutic Systems: Integration of biosensing with feedback-controlled therapeutic intervention, such as closed-loop insulin delivery systems [7].

Despite significant progress, challenges remain in sensor calibration, long-term stability, and large-scale validation [1]. Future research directions include expanding the repertoire of measurable biomarkers, improving understanding of correlations between non-invasive biofluid concentrations and blood chemistry, and enhancing the commercial translation of research prototypes into clinically validated devices [1] [2].

The field of medical technology has undergone a profound transformation, evolving from single-function therapeutic devices to sophisticated, continuous health monitoring platforms. This evolution began with the first implantable pacemakers and has now reached its current state with wearable biosensors capable of tracking a vast array of biochemical and biophysical parameters. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding this progression is not merely an academic exercise; it provides a critical framework for innovating next-generation diagnostic tools and personalized therapeutic strategies. These platforms are foundational to the shift from reactive, hospital-centered healthcare to a proactive, individual-centered model, enabling real-time biomarker quantification that informs clinical decisions and pharmaceutical research [8].

Historical Milestones: From Therapeutic to Diagnostic & Monitoring Tools

The journey of biomedical devices is marked by key innovations that progressively increased their functionality, miniaturization, and intelligence. The following table summarizes this evolution, highlighting the transition from simple life-sustaining devices to complex monitoring systems.

Table 1: Historical Evolution of Key Biomedical Device Technologies

| Era | Dominant Technology | Key Parameters Measured | Limitations & Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mid-20th Century | Early Implantable Pacemakers (e.g., VVI, AAI modes) [9] | Chamber sensing and pacing (Atrial/Ventricular) [9] | Large size, single-function, no sensor feedback, limited programmability [8] [9] |

| Late 20th Century | Advanced Pacemakers & Early Wearables (e.g., DDD mode, GlucoWatch) [8] [9] | A-V sequential pacing, non-invasive glucose [8] [9] | Invasive for implants, skin irritation for wearables, single analyte focus, limited battery life [8] |

| Early 21st Century | Consumer Fitness Trackers & CGM | Heart rate, step count, continuous glucose | Lack of clinical validation, focus on biophysical/one biochemical parameter, reliance on batteries [8] [10] |

| Present Day (2025) | All-in-One, Self-Powered Multi-Parameter Platforms [10] [11] | Metabolites (e.g., vitamins, amino acids), nutrients, hormones, drugs, ECG, activity [10] [12] [11] | Material stability, data security, miniaturization-information trade-offs, biocompatibility [10] |

This progression shows a clear trend: from therapeutic to diagnostic, from single-parameter to multi-parameter, from invasive to non-invasive, and from power-hungry to self-powered [8] [10].

Modern Multi-Parameter Sensing Platforms: Core Technologies

Contemporary platforms integrate several advanced technologies to achieve continuous, multi-analyte monitoring.

Sensing Modalities and Material Innovations

Modern wearable biosensors are classified based on their sensing principles and the type of data they collect:

- Biophysical Sensors: Measure parameters like heart rate, blood pressure, and temperature. These are widely marketized and used in consumer devices like smartwatches [8].

- Biochemical Sensors: Detect analytes in biological fluids like sweat, saliva, and tears. These represent the cutting edge of research, focusing on metabolites (glucose, lactate), nutrients (amino acids, vitamins), hormones, and pharmaceuticals [8] [12] [11]. A key advancement is the use of electrochemical biosensors, which offer high sensitivity, quick response, and low power consumption [8] [12]. Material science plays a critical role, with innovations in graphene electrodes, hybrid and metallic nanoparticles, and nanocomposites significantly improving sensor performance [8] [11].

The Paradigm of Self-Powered Systems

A critical challenge for continuous wearables is power. The latest research focuses on all-in-one, self-powered systems that harvest energy from the user's body or environment, eliminating the need for bulky batteries [10]. These systems integrate six essential modules:

- Energy Harvesting: Capturing energy from motion (Triboelectric/Piezoelectric Nanogenerators - TENGs/PENGs), heat (Thermoelectric Generators - TEGs), biofluids (Enzyme-Based Biofuel Cells - E-BFCs), or light (Solar Cells - SCs) [10].

- Energy Management: Converting and stabilizing the harvested energy using circuits and supercapacitors [10].

- Energy Storage: Storing excess energy for continuous operation [10].

- Signal Acquisition: Detecting the biochemical or biophysical signals via the sensors [10].

- Signal Processing: Analyzing and digitizing the collected data [10].

- Signal Transmission: Wirelessly sending information to external devices like smartphones [10].

Machine learning is increasingly used to optimize these systems by predicting energy availability and dynamically adjusting sensor operation to conserve power [10].

Mass Production through Advanced Manufacturing

Transitioning from lab prototypes to widespread use requires scalable manufacturing. A groundbreaking approach developed in 2025 involves inkjet printing arrays of core-shell cubic nanoparticles [11]. This technique allows for the mass production of inexpensive, long-lasting sweat sensors. The nanoparticles consist of a molecularly imprinted polymer (MIP) shell that acts as an artificial antibody, selectively capturing target molecules (e.g., vitamins, drugs), and a nickel hexacyanoferrate (NiHCF) core that generates an electrical signal. The presence of the target molecule alters this signal, enabling precise quantification [11].

Application Notes & Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Monitoring Metabolites and Nutrients via a Wearable Sweat Sensor

This protocol is adapted from a 2022 study for a fully integrated, wearable electrochemical biosensor capable of continuous, multiplexed analysis of trace-level metabolites and nutrients in sweat [12].

1. Principle: The sensor uses graphene electrodes functionalized with antibody-like Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) and redox-active reporter nanoparticles. Each MIP is specific to a target analyte (e.g., an essential amino acid or vitamin). The binding of the analyte to the MIP induces a measurable change in the electrochemical signal [12].

2. Workflow:

3. Key Steps:

- Sensor Fabrication: Construct the flexible sensor patch. Pattern graphene-based working, reference, and counter electrodes on a flexible substrate. Functionalize each working electrode with a specific MIP "ink" designed for a target analyte (e.g., tryptophan, vitamin C) [12] [11].

- System Integration: Integrate the sensor with a microfluidic channel for sweat sampling and transport, an iontophoresis module for controlled sweat induction, and the necessary electronics for potentiostatic control, signal processing, and wireless data transmission (e.g., Bluetooth Low Energy) [12].

- Calibration: Calibrate the sensor in vitro using artificial sweat solutions with known concentrations of the target analytes to establish a standard curve for signal-to-concentration conversion [12].

- Human Subject Testing: Apply the sensor to the volunteer's skin (e.g., forearm). Activate the iontophoresis module to induce sweat. Initiate continuous monitoring of the electrochemical signal (e.g., via chronoamperometry or square wave voltammetry) throughout the study period, which can include periods of rest and controlled physical exercise [12].

- Data Correlation & Validation: Periodically collect sweat and blood samples from the volunteer for parallel analysis using gold-standard methods (e.g., mass spectrometry). Correlate the sensor's real-time readings with the lab-based results to validate accuracy and assess serum-sweat correlations for specific biomarkers [12].

4. Applications:

- Real-time monitoring of amino acid intake and utilization during exercise [12].

- Assessment of metabolic syndrome risk by correlating amino acid levels in serum and sweat [12].

- Precision nutrition studies [12].

Protocol 2: Evaluating a Self-Powered, Printed Nanoparticle Sensor for Therapeutic Drug Monitoring (TDM)

This protocol is based on a 2025 study demonstrating the use of printed, molecule-selective nanoparticles for monitoring anti-tumor drug levels in cancer patients, pointing the way to personalized dosing [11].

1. Principle: Core-shell nanoparticles with a NiHCF core and a MIP shell are printed onto a substrate to form a sensor array. When a target drug molecule (e.g., a chemotherapeutic agent) binds to the shape-specific cavities in the MIP shell, it blocks the analyte fluid from reaching the NiHCF core, causing a measurable change in the electrical signal proportional to the drug concentration [11].

2. Workflow:

3. Key Steps:

- Nanoparticle Synthesis: Synthesize core-shell nanoparticles for each target drug. For a given chemotherapeutic drug, form the NiHCF core. Then, assemble the MIP shell in the presence of the drug molecules, which act as templates. Use a solvent to remove the template molecules, leaving behind cavities complementary in shape and size to the drug [11].

- Sensor Fabrication via Printing: Prepare an ink solution containing the synthesized nanoparticles. Use a commercial inkjet printer to deposit the ink onto a flexible, wearable substrate (e.g., a sweat patch) or an implantable substrate, creating a multiplexed array for different drugs [11].

- In-Vitro Characterization: Test the printed sensors in a simulated biological fluid (PBS or artificial sweat) containing known concentrations of the target drug. Perform calibration curves, selectivity tests against common interferents, and stability assessments over time [11].

- Pre-Clinical/Clinical Testing: For wearable application, deploy the patch on consenting cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. For implantable application, conduct studies in animal models, subcutaneously implanting the sensor. Continuously monitor the electrical signal from the sensor. In parallel, take periodic blood draws from the patient/animal to measure drug concentration using the standard method (e.g., Liquid Chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry - LC-MS/MS) [11].

- Data Analysis: Correlate the continuous sensor readouts with the discrete LC-MS/MS measurements from blood plasma. Analyze the pharmacokinetic profile of the drug and assess the feasibility of real-time, remote TDM [11].

4. Applications:

- Personalized dosing for chemotherapy and other conditions with narrow therapeutic windows [11].

- Remote monitoring of drug pharmacokinetics in clinical trials and routine care [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The development and implementation of advanced wearable biosensors rely on a suite of specialized materials and reagents. The following table details key components for constructing these platforms.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Wearable Biosensor Development

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Specific Example |

|---|---|---|

| Molecularly Imprinted Polymer (MIP) "Inks" | Serve as synthetic, stable recognition elements on sensor electrodes; selectively bind target analytes (vitamins, drugs, hormones) [12] [11]. | Core-shell nanoparticles with NiHCF core and MIP shell for vitamin C or tryptophan [11]. |

| Graphene & Carbon-based Inks | Form the base of flexible, high-surface-area working electrodes; provide excellent electrical conductivity for electrochemical sensing [8] [12]. | Graphene electrodes functionalized with MIPs and redox-active reporters [12]. |

| Nickel Hexacyanoferrate (NiHCF) | Acts as a stable, redox-active core in nanoparticles; generates an electrical signal when in contact with biofluids, which is modulated by analyte binding [11]. | Core material in printable, molecule-selective nanoparticles [11]. |

| Flexible Substrate Materials | Provide a conformal, skin-compatible base for mounting sensors and electronics; enable comfort and reliable skin contact for long-term monitoring [8] [10]. | Flexible polymers used in skin patches, smart textiles, and implantable devices [8] [10]. |

| Triboelectric/Piezoelectric Materials | Harvest biomechanical energy from body movement (walking, breathing) to power devices; enable self-powered systems [10]. | Materials in TENGs/PENGs for powering pacemakers or pulse monitors [10]. |

| Enzyme-Based Biofuel Cell (E-BFC) Components | Utilize biological fuels (glucose, lactate) in biofluids to generate electrical power; can also function as the sensing element itself [10]. | E-BFCs in sweat patches or contact lenses for simultaneous power generation and metabolite sensing [10]. |

The performance of modern multi-parameter platforms can be quantified against key metrics, as summarized in the table below. This data provides a benchmark for researchers evaluating system capabilities.

Table 3: Performance Metrics of Modern Multi-Parameter Sensing Platforms

| Performance Parameter | Representative Value/State-of-the-Art | Context & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Number of Simultaneously Measured Analytes | 3+ (e.g., Vitamin C, Tryptophan, Creatinine) [11] | Multiplexed panel for Long COVID monitoring via a single printed sensor array [11]. |

| Power Source Efficiency | >30% power conversion efficiency (Flexible Perovskite Solar Cells) [10] | Powers sweat sensors or implants; hybrid systems (TENG + SC + E-BFC) improve stability [10]. |

| Data Transmission Method | Wireless (e.g., Bluetooth) [10] [12] | Standard for commercial wearables and research prototypes for real-time data relay [10] [12]. |

| Sensor Lifetime & Stability | "Long-lasting," "highly stable... in biological fluids" [11] | Critical for long-term measurement of biomarkers; enabled by stable materials like NiHCF [11]. |

| Key Analytical Performance Metrics | Continuous, real-time monitoring of "trace levels" of metabolites and nutrients [12] | Enabled by in-situ calibration and advanced signal processing in integrated systems [12]. |

The advancement of wearable biosensors for continuous health monitoring is intrinsically linked to the development of robust, sensitive, and specific sensing modalities. Among the most prominent are electrochemical, optical, and piezoelectric biosensors. These transducers convert a biological recognition event into a quantifiable electrical, optical, or mechanical signal, respectively. The selection of an appropriate sensing modality is paramount for the development of effective wearable monitoring platforms, as it directly influences key performance parameters such as sensitivity, selectivity, power consumption, and integration potential. This document provides detailed application notes and experimental protocols for these three core sensing modalities, framed within the context of their application in continuous, real-time health monitoring for research and drug development.

Core Principles and Comparative Analysis

Biosensors are analytical devices that integrate a biological recognition element (bioreceptor) with a physico-chemical transducer [1]. The bioreceptor—such as an enzyme, antibody, nucleic acid, or whole cell—is responsible for the selective interaction with the target analyte. The transducer then converts this biorecognition event into a measurable signal that is proportionate to the analyte concentration [13].

The table below summarizes the fundamental characteristics, advantages, and challenges of the three primary biosensing modalities in the context of wearable health monitoring.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Core Biosensing Modalities for Wearable Applications

| Feature | Electrochemical Biosensors | Optical Biosensors | Piezoelectric Biosensors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transduction Principle | Measures electrical changes (current, potential, impedance) from biochemical reactions [14]. | Measures changes in light properties (intensity, wavelength, polarization) [15]. | Measures change in mass via mechanical stress-induced electrical signals (e.g., frequency shift) [16]. |

| Common Sub-types | Voltammetric/Amperometric, Impedimetric, Potentiometric, FET-based [14]. | Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR), Localized SPR, Fluorescence, Interferometric, Colorimetric [15] [13]. | Quartz Crystal Microbalance (QCM), Piezoelectric Cantilevers [16]. |

| Key Advantages | High sensitivity, portability, low cost, low power requirements, suitability for miniaturization [17] [14]. | High sensitivity and specificity, label-free detection, potential for multiplexing [15] [13]. | Label-free, real-time detection, high sensitivity to mass changes, simplicity [16] [18]. |

| Key Challenges for Wearables | Sensor drift, biofouling, calibration in complex matrices [17]. | Integration of optical components, miniaturization, potential for external light interference [15]. | Sensitivity to environmental vibrations, interference from liquid viscosity, integration challenges [16]. |

| Example Wearable Application | Real-time glucose monitoring in interstitial fluid [1]. | Monitoring of biomarkers via colorimetric sweat patches [17]. | Detection of pathogens or biomarkers in liquid samples [18]. |

Experimental Protocols for Wearable Integration

Protocol: Development of a Wearable Electrochemical Biosensor for Lactate Monitoring

Objective: To fabricate and characterize a flexible, amperometric biosensor for continuous lactate monitoring in sweat.

Principle: The enzyme lactate oxidase (LOx) is immobilized on a working electrode. LOx catalyzes the oxidation of lactate, producing hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂). An applied potential at the working electrode oxidizes H₂O₂, generating a current proportional to the lactate concentration [1] [14].

Materials:

- Substrate: Flexible polyimide or polyethylene terephthalate (PET) sheet.

- Electrodes: Screen-printed carbon (working, counter) and Ag/AgCl (reference) electrodes.

- Bioreceptor: Lactate oxidase (LOx) enzyme.

- Immobilization Matrix: Chitosan or Nafion solution.

- Equipment: Potentiostat, electrochemical cell, data acquisition system.

Procedure:

- Electrode Functionalization: Prepare a solution containing 5 mg/mL LOx in a 1% chitosan solution. Deposit 5 µL of this solution onto the working electrode area and allow it to dry at 4°C for 1 hour.

- Sensor Assembly: Integrate the functionalized electrode into a flexible, microfluidic sweat collection patch designed for epidermal attachment.

- Calibration: Connect the sensor to a portable potentiostat. Perform amperometric measurements (e.g., at +0.6 V vs. Ag/AgCl) in standard lactate solutions (e.g., 0.1 - 20 mM) in 0.1 M PBS, pH 7.4. Record the steady-state current.

- Data Analysis: Plot the calibration curve of current vs. lactate concentration. Determine the sensor's linear range, sensitivity (slope of the linear region), and limit of detection (LOD).

- In-Vitro Validation: Validate sensor performance using artificial sweat matrix to assess interference.

Protocol: Fabrication of an Optical SPR Biosensor for Biomarker Detection

Objective: To implement a Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) assay for the label-free, real-time detection of a specific protein biomarker (e.g., cortisol) in a buffer.

Principle: A laser beam is directed onto a gold-coated glass sensor chip, exciting surface plasmons at a specific resonance angle. The immobilization of a capture antibody and subsequent binding of the target analyte to the surface causes a change in the refractive index, leading to a shift in the resonance angle that is monitored in real-time [13].

Materials:

- SPR Instrument: Commercial SPR instrument (e.g., Biacore) or lab-built setup.

- Sensor Chip: Gold-coated glass chip with carboxymethylated dextran matrix.

- Bioreceptors: Monoclonal antibody specific to the target biomarker.

- Reagents: N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS), N-(3-Dimethylaminopropyl)-N′-ethylcarbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC), ethanolamine hydrochloride.

- Buffers: HBS-EP running buffer (10 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, 3 mM EDTA, 0.005% surfactant P20, pH 7.4).

Procedure:

- Surface Activation: Dock the sensor chip and prime the system with HBS-EP buffer. Inject a 1:1 mixture of 0.4 M EDC and 0.1 M NHS for 7 minutes to activate the carboxyl groups on the dextran matrix.

- Ligand Immobilization: Dilute the capture antibody to 20 µg/mL in 10 mM sodium acetate buffer (pH 5.0). Inject over the activated surface for 10 minutes to achieve covalent immobilization.

- Surface Blocking: Inject 1 M ethanolamine-HCl (pH 8.5) for 7 minutes to deactivate remaining activated esters.

- Binding Assay: Set a continuous flow of HBS-EP buffer. Inject a series of analyte (cortisol) solutions at varying concentrations (e.g., 0, 10, 50, 100 nM) for 3 minutes (association phase), followed by buffer flow for 5 minutes (dissociation phase).

- Data Analysis: Use the instrument's software to subtract signals from a reference flow cell. Fit the resulting sensorgrams to a 1:1 Langmuir binding model to determine the association ((k{on})) and dissociation ((k{off})) rate constants, and the equilibrium dissociation constant ((KD = k{off}/k_{on})).

Protocol: Quartz Crystal Microbalance (QCM) Assay for Pathogen Detection

Objective: To detect a bacterial pathogen (e.g., E. coli) using a QCM piezoelectric biosensor.

Principle: An antibody is immobilized on the gold surface of a quartz crystal. Binding of the bacterial cells to the antibodies increases the mass on the crystal surface, leading to a decrease in its resonant frequency, as described by the Sauerbrey equation [16].

Materials:

- QCM System: QCM instrument with flow cell and frequency oscillator.

- Sensor: AT-cut quartz crystal with gold electrodes.

- Bioreceptor: Anti-E. coli antibody.

- Reagents: 11-Mercaptoundecanoic acid (11-MUA), EDC, NHS.

- Buffers: Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), pH 7.4.

Procedure:

- Sensor Surface Functionalization: Incubate the QCM crystal in a 1 mM ethanolic solution of 11-MUA for 24 hours to form a self-assembled monolayer (SAM). Rinse with ethanol and dry under nitrogen.

- Antibody Immobilization: Place the crystal in the QCM flow cell. Flow PBS to establish a stable baseline frequency. Inject a solution of 0.4 M EDC and 0.1 M NHS for 15 minutes to activate the carboxyl groups of the SAM. Inject a solution of anti-E. coli antibody (50 µg/mL in PBS) for 30 minutes, allowing covalent amide bond formation.

- Baseline Stabilization: Flow PBS until a stable frequency is achieved. Record this frequency as the baseline, (F_0).

- Sample Measurement: Inject a series of E. coli suspensions in PBS of known concentrations (e.g., 10³ to 10⁶ CFU/mL) over the sensor surface. Monitor the frequency shift ((\Delta F)) in real-time for each concentration.

- Data Analysis: Use the Sauerbrey equation, (\Delta m = -C \cdot \Delta F / n), where (C) is the sensitivity constant of the crystal and (n) is the overtone number, to calculate the mass bound. Plot (\Delta F) versus E. coli concentration to establish a calibration curve.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Biosensor Development

| Item | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Enzymes (e.g., Glucose Oxidase, Lactate Oxidase) | Biocatalytic element that reacts specifically with the target analyte to produce a measurable product [1]. | Core recognition element in amperometric biosensors for metabolites. |

| Monoclonal Antibodies | High-specificity biorecognition elements for antigens and protein biomarkers [13]. | Immobilized on SPR chips or QCM crystals for label-free detection of biomarkers or pathogens. |

| N-Hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) / EDC | Cross-linking reagents for activating carboxyl groups to form stable amide bonds with proteins [13]. | Standard chemistry for covalent immobilization of antibodies on sensor surfaces (e.g., gold, dextran). |

| Chitosan / Nafion | Biocompatible polymers used for enzyme immobilization and as permselective membranes to block interferents [1]. | Entrapment of enzymes on electrode surfaces; rejection of negatively charged ascorbic acid in glutamate sensors. |

| Quartz Crystal Microbalance (QCM) Chip | Piezoelectric transducer that oscillates at a fundamental frequency sensitive to surface mass changes [16]. | Mass-sensitive platform for detecting binding of cells, proteins, or DNA. |

| Self-Assembled Monolayer (SAM) Thiols (e.g., 11-MUA) | Molecules that form ordered, stable layers on gold surfaces, providing functional groups for further modification [16]. | Creates a well-defined interface for subsequent bioreceptor immobilization on gold electrodes or QCM crystals. |

Workflow and Signaling Visualizations

Generalized Biosensor Workflow

This diagram illustrates the universal operational principle common to all biosensor modalities, from sample introduction to data output.

Electrochemical Sensing Pathway

This diagram details the specific signaling pathway in an enzymatic amperometric biosensor, such as one used for glucose or lactate detection.

Optical SPR Sensing Principle

This visualization depicts the core optical phenomenon of Surface Plasmon Resonance used for label-free biomolecular interaction analysis.

The development of wearable biosensors for continuous health monitoring represents a paradigm shift from reactive to predictive healthcare. This transition is being powered by breakthroughs in advanced materials science, particularly in the realms of graphene, functional nanomaterials, and flexible substrates. These materials are fundamentally redesigning the interface between biological systems and sensing technologies by providing the critical capabilities of mechanical compatibility with biological tissues, enhanced sensing sensitivity, and unprecedented miniaturization. Where traditional rigid electronics fail due to a mechanical mismatch with soft, dynamic human physiology, these advanced materials enable the creation of biosensing platforms that are conformable, stretchable, and even biodegradable [19] [1]. The integration of these materials is accelerating the advancement of biosensors from research curiosities to clinically viable devices capable of providing continuous, medical-grade physiological data outside clinical settings [20] [1].

The global flexible substrates market, projected to grow from USD 931.3 million in 2025 to USD 3,156.3 million by 2034, reflects the significant commercial investment in these enabling technologies [21]. This growth is driven by increasing demands across consumer electronics, healthcare, and automotive sectors. In healthcare specifically, flexible substrates are crucial for next-generation wearable devices that require durability, portability, and adaptability without compromising electronic performance [21]. This review examines the specific roles of graphene, nanomaterials, and flexible substrates in advanced biosensing platforms, providing detailed application notes and experimental protocols to guide research and development in this rapidly evolving field.

Material Properties and Functional Mechanisms

Property Comparison of Advanced Biosensing Materials

Table 1: Functional properties and biosensing applications of advanced materials.

| Material Category | Key Properties | Primary Roles in Biosensors | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Graphene | High electrical/thermal conductivity, large surface area, mechanical strength, flexibility [22] [20] | Transducer element, electrode material, sensing interface [22] | Potentiometric FET dopamine sensing, glucose monitoring [19] |

| Metallic Nanoparticles (Au, Ag) | Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance (LSPR), color tunability, high stability [22] [23] | Signal amplification, optical transduction, "hot spot" generation [22] [23] | SERS substrates for food contaminants, biomarker detection [23] [19] |

| Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) | Large surface area, high electrical conductivity, shock-bearing ability [22] [24] | Electrode modification, signal enhancement, flexible circuitry [22] | Piezoelectric nanogenerators, wearable pressure sensors [24] |

| Quantum Dots (QDs) | Color tunability, size-dependent optoelectronic properties [22] | Fluorescent tags, optical transduction elements [22] | Multiplexed detection, optical sensing platforms |

| Flexible Plastic Substrates (PET, Polyimide) | Mechanical flexibility, light weight, roll-to-roll process compatibility [25] [19] [21] | Structural support, device encapsulation, conformal interfaces [19] [21] | Flexible displays, skin-worn epidermal sensors [19] [21] |

| Cellulose Paper | Porosity, capillary action, biodegradability, low cost [25] [23] | Fluid transport, sample storage, disposable sensor matrix [25] [23] | Lateral flow assays, SERS substrates, point-of-care diagnostics [25] [23] |

Signaling and Enhancement Mechanisms in Nanomaterial-Enabled Biosensing

Advanced materials enhance biosensor performance through distinct physical mechanisms that amplify the biorecognition event into a measurable signal.

Electrochemical Sensing Mechanisms: Graphene and carbon nanotubes enhance electrochemical biosensors through their exceptional electrical properties. When functionalized with biorecognition elements (e.g., enzymes, antibodies), these materials facilitate efficient electron transfer between the bioreceptor and transducer during analyte binding. This results in enhanced sensitivity for amperometric, potentiometric, and impedimetric measurements [22] [19]. For instance, graphene-based field-effect transistors (FETs) can detect dopamine release from cells by measuring conductance changes with minimal interference when bent to a 3 cm radius, demonstrating both sensitivity and mechanical resilience [19].

Optical Sensing Mechanisms: Metallic nanoparticles, particularly gold and silver, enable highly sensitive optical biosensing through localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR). When these nanoparticles are irradiated with light at suitable wavelengths, they generate coherent electron oscillations that create intense, localized electromagnetic fields known as "hot spots" [23]. This phenomenon forms the basis for Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS), where plasmonic nanostructures can enhance Raman scattering signals by factors up to 10¹¹, enabling single-molecule detection [23]. The controlled creation of nanogaps between nanoparticles is critical for maximizing this enhancement effect [23].

Energy Harvesting Mechanisms: For self-powered wearable systems, nanomaterials enable the conversion of ambient energy from the body or environment into electrical power. Piezoelectric nanogenerators incorporating poly(vinylidene fluoride-co-trifluoroethylene) (P(VDF-TrFe)) nanofibers can transform mechanical energy from pulse waves or joint movements into electrical signals for both sensing and power generation [24]. Similarly, triboelectric nanogenerators (TENGs) can harvest energy from movement through contact-separation processes between nanomaterial-based layers with different electron affinities [24].

Figure 1: Signaling pathways in nanomaterial-enabled biosensors. Biological events are transduced into measurable signals through various enhancement mechanisms unique to nanomaterials.

Application Notes: Advanced Materials in Wearable Biosensors

Graphene in Flexible Electrochemical Sensors

Graphene's two-dimensional structure and exceptional electrical properties make it an ideal material for creating highly sensitive, flexible electrochemical biosensors. Devices incorporating graphene-based field-effect transistors (FETs) have demonstrated the capability to detect physiological concentrations of biomarkers like dopamine directly from cell cultures, while maintaining performance when mechanically deformed [19]. This combination of sensitivity and flexibility enables continuous monitoring of neurochemicals in unconventional, body-compliant form factors. The functionalization of graphene surfaces with specific biorecognition elements (enzymes, antibodies, aptamers) creates selective interfaces for target analytes while maintaining graphene's advantageous electronic properties. Manufacturing approaches include the direct transfer of graphene layers onto flexible substrates like polyimide or polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS), or the creation of graphene-polymer composites that offer both conductivity and stretchability [20] [19].

Nanomaterial-Enabled Optical Biosensing Platforms

Metallic nanoparticles functionalized with biorecognition elements serve as the foundation for highly sensitive optical biosensing platforms. Gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) and silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) exhibit strong localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) effects that transduce molecular binding events into measurable colorimetric or scattering signals. These nanoparticles can be incorporated into flexible substrates like cellulose paper to create low-cost, disposable biosensors for point-of-care applications [23]. SERS platforms leveraging nanoparticle "hot spots" have achieved enhancement factors up to 10¹¹, enabling detection of analytes at single-molecule levels [23]. Recent advances include the decoration of cellulose fiber networks with plasmonic nanoparticles, creating flexible SERS substrates that can be conformally applied to irregular surfaces for in-situ analysis [23]. These platforms are particularly valuable for detecting food contaminants, environmental pollutants, and disease biomarkers in resource-limited settings.

Flexible Substrates for Conformal Bio-Interfacing

The selection of appropriate flexible substrates is critical for ensuring reliable performance of wearable biosensors in dynamic, real-world conditions. Plastic polymers like polyethylene terephthalate (PET) and polyimide dominate the flexible substrates market, accounting for 46.2% of the global share, due to their excellent flexibility, lightweight nature, and compatibility with roll-to-roll manufacturing processes [21]. These materials provide mechanical support for electronic components while allowing the device to conform to curved body surfaces like the wrist or forehead. Emerging "epidermal" biosensors take this concept further by utilizing ultra-thin, skin-like substrates that can adhere directly to the epidermis for continuous analysis of biomarkers in sweat or interstitial fluid [1]. Beyond synthetic polymers, cellulose-based papers offer unique advantages including biodegradability, porosity for fluid transport, and extremely low cost, making them ideal for disposable diagnostic applications in resource-constrained settings [25] [23].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Impedimetric Viral Detection on Flexible Polyester Films

This protocol describes the capture and detection of viruses (e.g., HIV-1) using antibody-conjugated magnetic beads and impedance spectroscopy detection on a flexible polyester film with embedded electrodes [25].

Materials and Reagents:

- Flexible polyester film with two rail silver electrodes in microfluidic channels

- Magnetic beads (2.8 μm diameter)

- Biotinylated polyclonal anti-gp120 antibodies

- Viral samples (e.g., HIV-1 subtypes A, B, C, D, E, G)

- Control samples (virus-free DPBS)

- Glycerol solution (20% in deionized water)

- Lysis buffer (commercial RIPA buffer or equivalent)

- Biological samples (whole blood, plasma) for spiking experiments

Procedure:

- Bead Conjugation: Incubate magnetic beads with biotinylated anti-gp120 antibodies (1-2 μg per 1 mg beads) in DPBS for 1 hour at room temperature with gentle mixing.

- Virus Capture: Mix antibody-conjugated beads with viral samples (spiked into DPBS, whole blood, or plasma) at a ratio of 1 mg beads per 1 mL sample. Incubate for 2 hours with continuous mixing.

- Washing: Separate beads using a magnetic rack and wash four times with 20% glycerol solution to remove non-specifically bound materials.

- Viral Lysis: Resuspend washed beads in 100 μL lysis buffer and incubate for 15 minutes to release viral contents.

- Impedance Measurement:

- Apply 10 μL of lysate to the electrode area of the polyester film platform.

- Measure impedance magnitude and phase spectra over a frequency range of 100 Hz to 1 MHz.

- Focus analysis on impedance magnitude at 1,000 Hz, where maximum signal-to-noise ratio is observed.

- Data Analysis: Compare impedance magnitude of viral lysate samples to control samples. A significant decrease (13-30%) in impedance magnitude indicates positive detection [25].

Validation Notes:

- Specificity Testing: Include controls with unrelated viruses (e.g., Epstein-Barr virus) to confirm specificity of antibody-virus binding.

- Sample Volume Optimization: For low viral concentrations, increase sample volume up to 5 mL while maintaining the same bead quantity to improve detection sensitivity.

- Clinical Validation: Test with clinically relevant viral loads (10⁶-10⁸ copies/mL) matching acute infection stages.

Figure 2: Workflow for impedimetric viral detection on flexible polyester substrates.

Protocol: Cellulose-Based SERS Substrate Fabrication and Application

This protocol details the fabrication of flexible, cellulose-based substrates for Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS) and their application in detecting analytes at trace concentrations [23].

Materials and Reagents:

- Cellulose filter paper or nanocellulose film

- Metal precursors (chloroauric acid for gold, silver nitrate for silver)

- Reducing agents (sodium citrate, sodium borohydride)

- Capping agents (polyvinylpyrrolidone, citrate)

- Analyte solutions (e.g., Rhodamine 6G, pesticides, biomarkers)

- Ethanol and deionized water

- Oxygen plasma cleaner (optional)

Procedure:

- Substrate Pretreatment: Treat cellulose paper with oxygen plasma for 5 minutes (optional) to enhance surface hydrophilicity and nanoparticle adhesion.

- Nanoparticle Synthesis:

- For gold nanoparticles: Heat 0.01% chloroauric acid solution to boiling. Add 1% sodium citrate solution (1:10 v/v) with vigorous stirring. Continue heating until wine-red color develops.

- For silver nanoparticles: Add 2 mL of 0.1 M sodium borohydride to 50 mL of 0.1 mM silver nitrate with stirring. Add 1 mL of 1% sodium citrate as stabilizer.

- Substrate Functionalization:

- Immerse cellulose substrate in nanoparticle solution for 2-24 hours.

- Alternatively, drop-cast concentrated nanoparticle solution onto cellulose and dry at 60°C.

- For enhanced uniformity, use vacuum filtration to deposit nanoparticles onto cellulose membranes.

- Characterization: Verify nanoparticle distribution and density using scanning electron microscopy. Optimize "nanogap" distances between particles (typically 2-10 nm) for maximum SERS enhancement.

- SERS Measurement:

- Apply 2-5 μL of analyte solution to functionalized substrate and allow to dry.

- Acquire Raman spectra using appropriate laser wavelength (typically 532 nm or 785 nm).

- Focus laser on areas with high nanoparticle density ("hot spots").

- Enhancement Factor Calculation:

- Calculate Enhancement Factor (EF) using formula: EF = (ISERS / IRaman) × (NRaman / NSERS)

- Where ISERS and IRaman are SERS and normal Raman intensities, and NSERS and NRaman are number of molecules probed.

Technical Notes:

- Nanoparticle size control: Adjust metal-to-reductant ratio to control nanoparticle size (typically 20-80 nm for optimal SERS).

- Homogeneity: Use slow immersion method (24 hours) for more uniform nanoparticle distribution compared to drop-casting.

- Stability: Store functionalized substrates in vacuum desiccator to prevent nanoparticle oxidation.

- Calibration: Use Rhodamine 6G (10⁻⁶ to 10⁻⁹ M) as standard for EF calculation and performance validation.

Protocol: Self-Powered Wearable Sensor Integration

This protocol describes the integration of energy harvesting nanomaterials with biosensors to create self-powered wearable systems for continuous health monitoring [24].

Materials and Reagents:

- Piezoelectric polymer (P(VDF-TrFE) solution)

- Conductive electrodes (Ag nanowires, graphene ink)

- Flexible substrate (PDMS, PET, or polyimide)

- Encapsulation material (Ecoflex, PDMS)

- Biosensing element (enzyme, antibody, according to application)

- Connecting wires/silver epoxy

Procedure:

- Nanogenerator Fabrication:

- Spin-coat P(VDF-TrFE) solution onto flexible substrate at 2000 rpm for 60 seconds.

- Anneal at 120°C for 2 hours to enhance piezoelectric β-phase crystallization.

- Deposit top and bottom electrodes using Ag nanowire networks or graphene ink.

- Poling: Apply electric field (50-100 MV/m) at 80°C for 1 hour to align dipole moments.

- Sensor Integration:

- Fabricate biosensor component (e.g., electrochemical sensor, strain sensor) adjacent to nanogenerator on same substrate.

- Connect nanogenerator output to sensor circuitry using stretchable interconnects.

- System Encapsulation:

- Encapsulate entire device in thin layer of PDMS or Ecoflex (100-500 μm thickness) using spin-coating or lamination.

- Ensure encapsulation maintains flexibility while protecting from moisture and mechanical damage.

- Performance Validation:

- Test energy output by applying simulated body movements (flexion, compression).

- Measure open-circuit voltage and short-circuit current using oscilloscope.

- Verify sensor functionality when powered solely by nanogenerator.

- On-Body Testing:

- Mount device on joint (wrist, knee) or chest for real-world performance assessment.

- Monitor continuous operation duration and power management efficiency.

Optimization Guidelines:

- Energy Output: Incorporate high-aspect ratio nanomaterials (ZnO nanowires, BaTiO₃ nanoparticles) into polymer matrix to enhance piezoelectric coefficient.

- Flexibility: Use porous or fiber-based electrode structures to maintain conductivity during stretching.

- Biocompatibility: Select encapsulation materials with demonstrated skin compatibility for long-term wear.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key research reagents and materials for developing advanced biosensing platforms.

| Category/Item | Specific Examples | Research Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flexible Substrates | PET, Polyimide, PDMS, cellulose paper [25] [19] [21] | Structural support enabling bendable, conformal devices | Plastic films dominate market (46.2%); paper offers biodegradability [21] |

| Conductive Nanomaterials | Graphene, CNTs, Ag nanowires [22] [20] [24] | Electrodes, interconnects, transducer elements | Provide conductivity while maintaining flexibility under deformation |

| Plasmonic Nanoparticles | Gold nanospheres, silver nanocubes, Au-Ag core-shell [22] [23] | LSPR generation for optical sensing, SERS "hot spots" | Control nanogap (2-10 nm) for maximum field enhancement [23] |

| Biorecognition Elements | Anti-gp120 antibodies, glucose oxidase, DNA aptamers [25] [22] [1] | Selective target capture and molecular recognition | Stability on flexible/nanomaterial surfaces requires optimization |

| Energy Harvesting Materials | P(VDF-TrFE), BTO-PDMS composites, triboelectric layers [24] | Self-powering from body movement, thermal gradients | Piezoelectric polymers require poling for optimal performance |

| Encapsulation Materials | Ecoflex, PDMS, parylene, polyurethane [19] [1] | Environmental protection, biocompatibility, device integrity | Must balance barrier properties with mechanical flexibility |

The integration of graphene, nanomaterials, and flexible substrates is fundamentally transforming the capabilities of wearable biosensors for continuous health monitoring. These advanced materials enable the creation of devices that successfully overcome the historical limitations of conventional rigid electronics, providing unprecedented mechanical compatibility with biological systems while enhancing sensing performance through unique physical and chemical properties. As research advances, several key challenges and opportunities are emerging that will shape the future development of these technologies.

Future progress will likely focus on enhancing the multifunctionality of these materials systems, creating platforms capable of simultaneously monitoring multiple biomarkers with high specificity and sensitivity. The development of robust self-powering systems through advanced energy harvesting nanomaterials will be critical for achieving truly autonomous operation [24]. Additionally, the transition from proof-of-concept demonstrations to clinically validated tools requires extensive large population studies to establish correlations between biomarker concentrations in easily accessible biofluids (sweat, tears) and blood chemistry [1]. As these technologies mature, interdisciplinary collaboration between materials scientists, engineers, and clinical researchers will be essential to address complex challenges in biocompatibility, signal stability, and manufacturing scalability. With continued advancement, biosensing platforms leveraging these advanced materials have the potential to revolutionize personal healthcare by providing continuous, real-time physiological information that enables truly predictive and personalized medicine.

The advancement of wearable biosensors for continuous health monitoring is fundamentally driven by the convergence of three core enabling technologies: microfluidics, wireless communication, and energy harvesting. These technologies synergistically address the critical challenges of miniaturization, real-time data accessibility, and power autonomy, which are essential for practical, user-friendly biosensing systems. Microfluidic components enable the precise manipulation of minute biofluid samples, such as sweat, tears, or interstitial fluid, directly at the wearer's skin [26] [1]. Wireless communication modules facilitate the seamless transmission of captured physiological data to external devices like smartphones or cloud platforms, enabling real-time analytics and remote patient monitoring [27]. Furthermore, energy harvesting systems provide sustainable power by converting ambient energy from the user's environment or body into electrical energy, thereby reducing or eliminating reliance on traditional batteries and enhancing device longevity [28] [27]. This integration is paving the way for a new generation of autonomous, "lab-on-a-chip" wearable platforms that promise to revolutionize personalized healthcare and continuous physiological monitoring [26] [29].

Technology-Specific Application Notes & Protocols

Microfluidics for Wearable Biosensors

Application Note AN-MF001: On-Body Biofluid Handling and Analysis Microfluidic systems in wearable biosensors are designed for the autonomous sampling, transport, and analysis of epidermal biofluids like sweat. These systems utilize networks of microscale channels, pumps, and valves fabricated from flexible polymers to ensure conformal contact with the curved and dynamic surface of human skin. A critical function is the continuous wicking of freshly secreted sweat to sensing chambers while preventing the accumulation of stale sample, which is achieved through sophisticated channel design and capillary action [26] [1]. The primary challenge is maintaining consistent and reproducible sample transport over extended wear periods, as variations in sweat rate and skin topography can affect sensor performance.

Protocol PR-MF001: Fabrication of a PDMS-Substrate Microfluidic Chip for Sweat Sampling

- Objective: To fabricate a flexible, skin-adherent polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) microfluidic chip for continuous sweat collection and routing to electrochemical sensor electrodes.

Materials:

- SYLGARD 184 Silicone Elastomer Kit (Dow DuPont)

- SU-8 photoresist and SU-8 developer

- Silicon wafer (4-inch)

- Plasma surface treater

- Oven

- Acetone and Isopropyl Alcohol (IPA)

- Laser printer and transparency film or high-resolution photomask

Procedure:

- Master Mold Fabrication: a. Clean the silicon wafer sequentially with acetone, IPA, and deionized water; dry with nitrogen. b. Spin-coat SU-8 photoresist onto the wafer to achieve a thickness of 100 µm. c. Soft-bake the wafer according to the SU-8 datasheet. d. Expose the photoresist to UV light through a photomask defining the microchannel design. e. Perform a post-exposure bake. f. Develop the wafer in SU-8 developer to reveal the relief structure of the channels. g. Hard-bake the master mold at 150°C for 10 minutes to improve robustness.

- PDMS Chip Casting: a. Mix the PDMS base and curing agent in a 10:1 weight ratio. Degas the mixture in a desiccator until no bubbles remain. b. Pour the PDMS mixture over the master mold placed in a Petri dish. c. Degas again to remove any bubbles introduced during pouring. d. Cure the PDMS in an oven at 65°C for 4 hours. e. Carefully peel the cured PDMS slab, containing the negative imprint of the channels, from the master mold.

- Bonding and Integration: a. Cut the PDMS slab to size and create fluidic inlet/outlet ports using a biopsy punch. b. Treat the PDMS surface and a pre-fabricated sensor substrate (e.g., with screen-printed electrodes) with oxygen plasma for 45 seconds. c. Immediately bring the activated surfaces into contact to form an irreversible seal. d. Post-bake the assembled device at 80°C for 30 minutes to strengthen the bond.

Validation: Verify channel integrity and flow by introducing a colored dye (e.g., food dye) at the inlet and observing its capillary-driven progression through the network to the outlet/sensor zone.

Wireless Communication for Data Transmission

Application Note AN-WC001: Low-Power Telemetry for Physiological Data Wireless communication is indispensable for transforming a wearable sensor into a node in a connected health ecosystem. For wearables, the selection of a wireless technology involves a critical trade-off between data rate, range, and power consumption. Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) is predominantly favored for consumer wearables due to its low power profile and universal compatibility with smartphones [27]. For applications requiring longer range or operation in challenging environments, protocols like LoRaWAN or Zigbee are employed. A key design principle is the implementation of duty cycling, where the radio is powered on only during data transmission bursts to minimize average power consumption [28].

Protocol PR-WC001: Integration of BLE for Real-Time Data Streaming from a Biosensor Patch

- Objective: To integrate a BLE module with a microcontroller and biosensor to enable wireless streaming of physiological data (e.g., glucose concentration) to a mobile device.

Materials:

- BLE SoC (System-on-Chip), e.g., Nordic Semiconductor nRF52840

- Microfluidic biosensor patch with analog signal output

- Stable power source (e.g., 3.3V button cell battery or embedded energy harvester)

- JTAG/SWD programmer and associated software

- Mobile phone with custom-developed or generic BLE terminal application.

Procedure:

- Hardware Interfacing: a. Connect the analog output pin of the biosensor's potentiostat to an ADC (Analog-to-Digital Converter) input pin on the BLE SoC. b. Establish common ground between the biosensor, SoC, and power supply. c. Ensure stable 3.3V power is supplied to all active components.

- Firmware Development: a. Develop firmware (e.g., in C/C++ using the nRF5 SDK) to initialize the SoC's ADC at a specified sampling rate (e.g., 1 Hz). b. Program the ADC to read the sensor's voltage, which is proportional to the analyte concentration. c. Implement the BLE stack and define a custom GATT (Generic Attribute) service with a characteristic to hold the sensor data. d. Configure the device to advertise itself with a recognizable name and to allow connections from a central device (smartphone). e. Write the digitized and processed sensor reading to the GATT characteristic at the defined sampling interval.

- Mobile Application & Data Logging: a. On the mobile side, develop an app (e.g., using Android's BLE API) that scans for and connects to the sensor's unique BLE address. b. Upon connection, the app should discover services and subscribe to notifications for the data characteristic. c. Implement a data parser to convert the incoming byte stream into numerical values and display them in real-time on the phone's screen. d. Incorporate functionality to log the time-stamped data to a local file or transmit it to a cloud database.

Validation: Measure the current draw of the system during advertising, connected, and sleep states using a precision multimeter to ensure it meets power budget constraints.

Energy Harvesting for System Autonomy

Application Note AN-EH001: Ambient Energy Scavenging for Wearables Energy harvesting technologies liberate wearable biosensors from the limitations of battery capacity by converting ambient energy into electricity. Common strategies include the use of flexible photovoltaic cells to harvest light, thermoelectric generators (TEGs) to convert body heat, and piezoelectric or triboelectric devices to capture energy from body movement [28] [27]. A critical component of any energy harvesting system is the Power Management Unit (PMU), which performs maximum power point tracking (MPPT), regulates the variable harvested power, and manages the charging of a small buffer battery or supercapacitor to handle peak power demands beyond the harvester's continuous output [28].

Protocol PR-EH001: System Integration of a Solar Energy Harvester with a Supercapacitor Buffer

- Objective: To power a wearable biosensor patch by integrating a flexible solar cell with a PMU and a supercapacitor for energy storage.

Materials:

- Flexible amorphous silicon solar cell (e.g., 5V, 10mA under indoor light)

- Power Management IC (PMIC), e.g., BQ25570 from Texas Instruments

- Low-leakage 1 F supercapacitor

- Wearable biosensor platform (load)

- Oscilloscope, multimeter, variable light source.

Procedure:

- Characterization of the Harvester: a. Place the solar cell under a calibrated light source simulating indoor (200 lux) and outdoor (10,000 lux) conditions. b. Using a variable resistor as an electronic load, perform a current-voltage (I-V) sweep to determine the open-circuit voltage (VOC), short-circuit current (ISC), and maximum power point (MPP) for each condition.

- PMU and Storage Integration: a. Solder the solar cell's output to the "VIN" pins of the BQ25570 PMIC evaluation board. b. Connect the 1 F supercapacitor to the "VBAT" pins of the PMIC for energy storage. c. Connect the output of the PMIC ("VOUT") to the power input rail of the biosensor platform. d. Configure the PMIC's resistor settings according to the datasheet to set the MPPT voltage (based on step 1b) and the desired output voltage (e.g., 3.3V).

- System-Level Validation: a. Place the entire system under a light source and monitor the supercapacitor voltage with an oscilloscope to observe the charging profile. b. Once the supercapacitor is charged to the PMIC's turn-on voltage, verify that the biosensor platform powers up and begins normal operation (sensing and wireless transmission). c. Characterize the system's operational lifetime by measuring the time it takes for the supercapacitor to discharge from its maximum voltage to the PMIC's undervoltage lockout threshold under a continuous load.

Validation: The system is validated if it can sustain continuous operation of the biosensor (including its highest power state, e.g., wireless transmission) for a target duration under a defined, cyclic illumination profile (e.g., 12 hours of 200 lux light / 12 hours dark).

Integrated System Workflow

The seamless operation of an advanced wearable biosensor relies on the orchestrated interaction of microfluidics, sensing, energy management, and wireless communication. The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and data flow from sample collection to user feedback.

Diagram Title: Wearable Biosensor System Workflow

Quantitative Technology Comparison

The selection of appropriate technologies for a wearable biosensor depends on specific application requirements. The tables below summarize key performance metrics and parameters for the discussed enabling technologies.

Table 1: Comparison of Wireless Communication Technologies for Wearable Biosensors

| Technology | Typical Data Rate | Range | Power Consumption | Primary Use Case in Biosensors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) | 1-2 Mbps | Short (10-100m) | Very Low | Streaming to smartphone, frequent data updates [27] |

| Near-Field Communication (NFC) | 100-400 kbps | Very Short (<0.2m) | Zero (Powered by Reader) | Patch interrogation, single-read events [27] |

| LoRaWAN | 0.3-50 kbps | Long (2-15 km) | Low | Remote area monitoring, infrequent transmissions [28] |

| Zigbee | 250 kbps | Short (10-100m) | Low | Body area networks, multi-sensor systems [28] |

Table 2: Comparison of Energy Harvesting Modalities for Wearables

| Technology | Typical Power Density | Constraints | Best Suited Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Photovoltaic (Indoor) | 10-100 µW/cm² | Light availability, surface area | Wristwear, headbands [28] [27] |

| Thermoelectric (Body Heat) | 20-60 µW/cm² | Small skin-air ΔT, thermal resistance | Chest patches, tight-fitting bodywear [27] |

| Piezoelectric (Motion) | ~10 µW/cm³ | Dependent on user activity level | Footwear, joint-mounted sensors [27] |

| RF Energy Harvesting | ~0.1 µW/cm² | Very low power, distance from source | Supplementing other sources, passive sensors [28] |

Table 3: Key Market Growth Metrics for Biosensor Technologies (2025-2030)

| Metric | Projected Value / CAGR | Note |

|---|---|---|

| Global Biosensors Market (2030) | USD 54.37 Billion | Projected value [30] |

| Market CAGR (2025-2030) | 9.5% | Compound Annual Growth Rate [30] [31] |

| Wearable Biosensors Segment | Highest Growth CAGR | Within the biosensor product market [30] [31] |

| Optical Biosensor Technology | Highest Growth CAGR | Within biosensor technology segments [30] [31] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent & Material Solutions

Table 4: Essential Materials and Reagents for Wearable Biosensor Development

| Item | Function / Application | Specific Example(s) |

|---|---|---|

| PDMS (Polydimethylsiloxane) | Flexible, biocompatible substrate for microfluidic channels and sensor encapsulation [26] [1] | SYLGARD 184 (Dow DuPont) |

| SU-8 Photoresist | Epoxy-based negative photoresist for creating high-aspect-ratio master molds for soft lithography [26] | SU-8 2050, SU-8 3050 (Kayaku) |

| Screen-Printed Electrodes (SPEs) | Low-cost, mass-producible electrochemical sensor platforms. | Carbon, Ag/AgCl, Gold working electrodes |

| Enzymatic Bioreceptors | Provide high specificity for target analytes (e.g., metabolites) in catalytic biosensors [1] | Glucose Oxidase (for glucose), Lactate Oxidase (for lactate) |

| Aptamers | Synthetic nucleic acid-based bioreceptors for affinity-based sensing of proteins, hormones, etc. [26] [1] | Custom-selected sequences for targets like cortisol or thrombin |

| Ion-Selective Membranes | Enable potentiometric detection of specific electrolytes in biofluids [27] | Valinomycin membrane (for K⁺), TRIEN membrane (for Na⁺) |

| PEDOT:PSS | Conductive polymer used for ion-to-electron transduction, enhancing stability of solid-contact ion-selective electrodes [27] | Clevios PH1000 |

| Nafion | Cation-exchange polymer membrane used to mitigate biofouling and interferent effects in electrochemical sensors [1] | Nafion perfluorinated resin solution |

From Lab to Life: Advanced Applications in Therapeutics and Remote Patient Monitoring

Therapeutic Drug Monitoring (TDM) is undergoing a transformative shift from intermittent, invasive blood draws to continuous, real-time measurement enabled by advances in wearable and implantable biosensor technology. These devices leverage synthetic biology, electrochemical sensing, and intelligent data processing to provide unprecedented insight into pharmacokinetic profiles, enabling truly personalized medicine [32] [33]. This paradigm is particularly impactful for drugs with narrow therapeutic windows, such as anti-Parkinson's agents, antibiotics, and analgesics. This document provides detailed application notes and experimental protocols for implementing these advanced biosensing systems in a research and development context, framed within the broader thesis of wearable biosensors for continuous health monitoring.

Technological Foundations of Continuous TDM

The core of modern TDM lies in biosensors that can operate continuously in situ. A leading example is the SENSBIT (Stable Electrochemical Nanostructured Sensor for Blood In situ Tracking) platform, a microfabricated soft needle that can monitor drug concentrations in flowing blood for up to seven days [32]. This represents a dramatic improvement over previous devices that failed after approximately 11 hours.

Core Sensing Mechanism: The SENSBIT sensor utilizes synthetic antibodies called aptamers that function as molecular switches. Upon encountering a target drug molecule, the aptamer changes its three-dimensional conformation. This structural change generates a measurable electrochemical signal, allowing for precise quantification of the target analyte [32]. The modular design of this technology means it can be adapted to monitor a wide range of therapeutics, from small-molecule antibiotics to complex biologics [32].

Quantitative Performance Data of Featured Platforms

The following tables summarize the key performance metrics and application parameters for the featured TDM technologies, providing a basis for experimental selection and design.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Representative Biosensors for TDM

| Sensor Platform | Target Analytic | Monitoring Duration | Key Performance Metric | Signal Retention |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SENSBIT (Implantable) [32] | Kanamycin (Antibiotic) | Up to 7 days | Continuous, real-time data in flowing blood | >70% after 1 month in human serum |

| ACM Wrist Device (Wearable) [34] | Motor symptoms, Sleep, Autonomic function (Parkinson's) | 7 consecutive days | Multidimensional circadian rhythms (A/T Ratio) | N/A (Continuous data stream) |

| ePatch (Wearable) [33] | Heart rhythm (Adverse drug event detection) | >24 hours (Extended) | Wireless ECG data transmission | N/A (Continuous data stream) |

Table 2: Application Parameters for Different Drug Classes

| Drug Class | Example Drug | TDM Need | Compatible Sensor Type | Key Measured Parameter |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aminoglycoside Antibiotics | Kanamycin | Narrow therapeutic window [32] | Implantable (e.g., SENSBIT) | Real-time plasma concentration [32] |

| Anti-Parkinson's Agents | Levodopa | Pulsatile dosing; motor fluctuation management [34] | Wearable (e.g., ACM) | Acceleration, Time in Movement, A/T Ratio [34] |

| Analgesics | (To be selected) | Toxicity risk with chronic use | Implantable / Wearable (Platform) | Real-time plasma concentration |

Experimental Protocols for Real-Time TDM

Protocol: Continuous Monitoring of Antibiotics via Implantable Aptamer-Based Sensor

This protocol details the methodology for tracking antibiotic concentrations, such as kanamycin, using an implantable electrochemical sensor [32].

I. Sensor Preparation and Calibration

- Materials: SENSBIT sensor array, target drug (e.g., Kanamycin), artificial serum, potentiostat.

- Procedure:

- Pre-conditioning: Immerse the sensor in a buffer solution (e.g., PBS, pH 7.4) for 30 minutes to stabilize the electrochemical baseline.