Whole Cell vs. Enzymatic Biosensors for Pesticide Detection: A Comparative Guide for Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and scientists on the two predominant biosensing technologies for pesticide monitoring: enzymatic and whole-cell biosensors.

Whole Cell vs. Enzymatic Biosensors for Pesticide Detection: A Comparative Guide for Researchers

Abstract

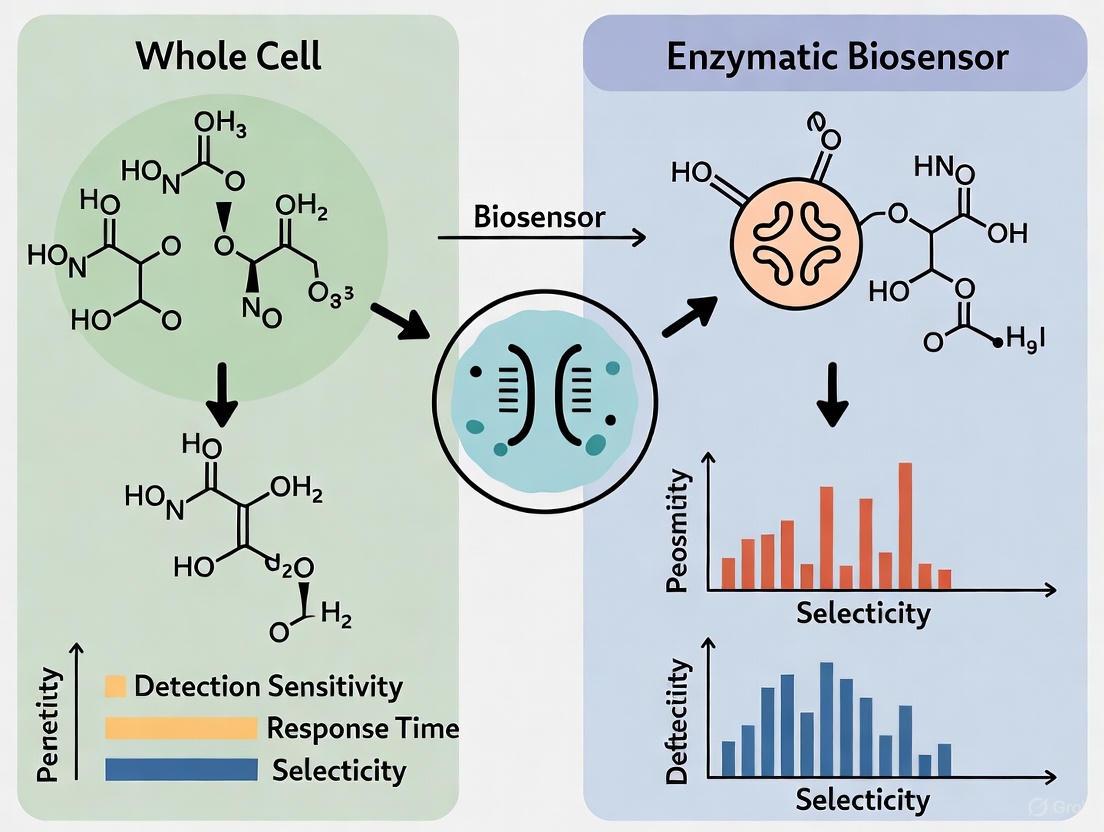

This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and scientists on the two predominant biosensing technologies for pesticide monitoring: enzymatic and whole-cell biosensors. We explore the foundational principles of each technology, detailing how enzymatic biosensors leverage isolated enzyme kinetics while whole-cell systems utilize complex cellular machinery. The scope covers the latest methodological advances, including genetic engineering of microbial chassis and nanozyme development, alongside practical applications in environmental and food safety monitoring. A critical comparative evaluation addresses key performance metrics—sensitivity, specificity, stability, and real-world applicability—empowering professionals to select optimal biosensor configurations for specific research and development objectives in biomedical and environmental health.

Core Principles: How Enzymatic and Whole-Cell Biosensors Work

The detection of pesticides and other environmental contaminants relies heavily on biosensor technology, which connects a biological recognition element to a signal transducer. Within this field, two distinct technological paradigms have emerged: biosensors based on isolated enzymes and those utilizing whole-cell systems. The fundamental distinction lies in the complexity of the biological recognition element. Isolated enzyme biosensors employ purified enzyme molecules, such as acetylcholinesterase (AChE), to catalyze specific reactions with a target analyte, generating a measurable product [1] [2]. In contrast, whole-cell biosensors use living microbial or other cells as integrated sensing machines, where the recognition of a target substance is coupled to an internal response, such as the expression of a reporter gene [3] [4].

The choice between these paradigms is central to the design of any biosensing strategy for pesticide research. Isolated enzyme systems offer high catalytic efficiency and rapid response, leveraging the specificity of enzyme-substrate interactions [1]. Whole-cell systems, on the other hand, provide a more robust sensing platform that can mimic biological effects and self-replicate, but often with slower response times [3]. This technical guide provides an in-depth comparison of these technologies, detailing their components, operational principles, and experimental implementation to inform their application in pesticide detection.

Isolated Enzyme Biosensors: Principles and Components

Core Architecture and Working Principle

An isolated enzyme biosensor functions by integrating a biological recognition element (the enzyme) with a physicochemical transducer [1]. Its operation follows a defined sequence:

- Recognition: The target analyte (substrate) specifically binds to the enzyme's active site.

- Catalysis: The enzyme catalyzes the conversion of the substrate into one or more products.

- Transduction: A physicochemical change resulting from the reaction—such as the production or consumption of electrons, protons, heat, or light—is detected by the transducer.

- Signal Output: The transducer converts this change into a quantifiable electrical or optical signal proportional to the analyte concentration [1].

A key application in pesticide detection is the inhibition-based biosensor. For organophosphorus and carbamate pesticides, the enzyme acetylcholinesterase (AChE) is commonly used. In its standard activity, AChE hydrolyzes the neurotransmitter acetylcholine. In a biosensor, this reaction produces a detectable product, such as thiocholine from acetylthiocholine. When pesticides are present, they inhibit AChE, leading to a measurable reduction in product formation and signal output, which correlates with the pesticide concentration [1] [5].

Transducer Mechanisms and Immobilization Techniques

The transducer is critical for signal conversion. Common transducer types in enzyme biosensors include:

- Electrochemical Transducers: The most common type, which includes:

- Optical Transducers: Measure changes in light properties, such as absorbance, fluorescence, or chemiluminescence, due to the enzymatic reaction [1] [2].

- Thermal Transducers (Thermistor): Detect the heat released or absorbed during the enzymatic catalysis [1].

To ensure stability and reusability, the enzyme must be effectively immobilized onto the transducer surface. Key immobilization strategies are compared in the table below [1].

Table 1: Enzyme Immobilization Techniques for Biosensor Fabrication

| Technique | Mechanism | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Covalent Bonding | Formation of stable covalent bonds between enzyme and functionalized support. | Strong attachment; high stability; minimal enzyme leakage. | Potential loss of enzyme activity due to harsh conditions. |

| Entrapment | Enzyme physically confined within a polymeric network or gel. | Mild conditions; protection of enzyme from the external environment. | Diffusion limitations for substrate and product; possible leaching. |

| Physical Adsorption | Enzyme bound via weak forces (Van der Waals, ionic). | Simple procedure; no chemical modification. | Weak binding; enzyme desorption over time. |

| Cross-linking | Enzymes linked to each other or to a support via cross-linking agents. | High enzyme loading; stable matrix. | Can reduce enzymatic activity; may be difficult to control. |

Whole-Cell Biosensors: Engineering Cellular Machinery

Synthetic Biology Design Principles

Whole-cell biosensors (WCBs) are constructed using synthetic biology to engineer genetic circuits within a host organism (the "chassis cell"), such as E. coli or yeast. These circuits comprise two core functional elements [3]:

- Sensing Element: This is typically a transcription factor or a riboswitch that acts as the molecular "lock" for the "key" (the target analyte, e.g., a pesticide or heavy metal). The sensing element regulates the expression of a downstream reporter gene.

- Reporting Element: This is a gene that codes for a easily detectable protein, such as a fluorescent protein (e.g., GFP), an enzyme that catalyzes a colorimetric reaction, or a gas.

When the target analyte enters the cell and binds to the sensing element, it triggers a conformational change. This change allows RNA polymerase to bind to the promoter and transcribe the reporter gene, leading to the production of the reporter protein. The resulting signal (e.g., fluorescence intensity) is quantitatively related to the analyte concentration [3] [4].

Advanced Circuit Engineering for Performance Enhancement

A significant challenge in WCB design is balancing high sensitivity with low background signal leakage. Advanced regulatory circuits have been developed to address this. For instance, a dual-input promoter was engineered for ultra-trace cadmium detection (LC100-2 biosensor), incorporating the LacI protein as both a signal amplifier and a negative feedback module [4]. This design dramatically improved sensitivity while minimizing background leakage, demonstrating the power of sophisticated genetic circuit design in creating high-performance biosensors.

Comparative Analysis: Performance and Applications

The technical distinctions between isolated enzyme and whole-cell biosensors lead to direct differences in performance metrics and suitability for specific applications in pesticide research.

Table 2: Quantitative Comparison of Isolated Enzyme and Whole-Cell Biosensors

| Parameter | Isolated Enzyme Biosensors | Whole-Cell Biosensors |

|---|---|---|

| Response Time | Seconds to minutes [1] | Minutes to hours [3] |

| Operational Stability | Moderate to low (enzyme denaturation) [1] | High (self-regenerating) [3] |

| Detection Limit | ~0.38 pM for OPs (fluorescence-based) [5] | ~0.00001 nM for Cd²⁺ (engineered circuit) [4] |

| Specificity | Very high (enzyme-substrate specificity) [1] | Can be engineered; may detect class effects [3] |

| Sample Compatibility | Can be affected by matrix interferents [1] | High, due to cellular homeostasis [3] |

| Lifespan & Storage | Limited (requires stable enzyme storage) [1] | Long (cells can be revived from frozen stocks) [3] |

| Cost & Production | Enzyme purification can be costly [1] | Low cost; mass-produced via cell division [3] |

| Toxicity Assessment | Measures specific biochemical interaction | Can report on integrated bioavailability and cellular toxicity |

Experimental Protocols for Biosensor Implementation

Protocol for Fabricating an Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) Inhibition Biosensor

This protocol details the creation of a sensor for organophosphorus pesticides based on AChE inhibition and electrochemical detection [1] [5].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Acetylcholinesterase (AChE): Biological recognition element; catalyzes substrate reaction.

- Acetylthiocholine (ATCh) or Acetylcholine: Enzyme substrate; reaction produces detectable signal.

- Electrode (e.g., Glassy Carbon, Screen-Printed): Signal transducer platform.

- Immobilization Matrix (e.g., Chitosan, Nafion, BSA-Glutaraldehyde): Stabilizes enzyme on electrode.

- Buffer (e.g., Phosphate Buffer Saline, PBS): Maintains stable pH for enzyme activity.

- Nanomaterial (e.g., Graphene, Carbon Nanotubes, Metal Nanoparticles): Enhances electron transfer and sensor sensitivity.

Procedure:

- Electrode Pretreatment: Clean the working electrode (e.g., glassy carbon) by polishing with alumina slurry and rinsing with deionized water.

- Nanomaterial Modification (Optional): Deposit a suspension of nanomaterials (e.g., graphene oxide) onto the electrode surface and allow to dry to enhance the surface area and conductivity.

- Enzyme Immobilization: Apply a mixture of AChE and the immobilization matrix (e.g., a solution of AChE in chitosan) onto the modified electrode surface. Allow the matrix to cross-link or solidify, entrapping the enzyme.

- Sensor Calibration: Immerse the biosensor in a stirred buffer solution. Apply a constant potential and record the background current. Add successive aliquots of the substrate (ATCh) and record the steady-state current generated from the enzymatic production of thiocholine.

- Inhibition Assay: Incubate the biosensor with a sample containing the potential pesticide (inhibitor) for a fixed time (e.g., 10-15 minutes). Wash the sensor and repeat the calibration step with ATCh.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the percentage of enzyme inhibition using the formula:

% Inhibition = [(I_control - I_sample) / I_control] * 100, whereI_controlis the current before inhibition andI_sampleis the current after inhibition. Quantify pesticide concentration by comparing against a calibration curve of inhibition vs. standard pesticide concentration.

Protocol for a Whole-Cell Biosensor for Heavy Metal Detection

This protocol outlines the use of a genetically engineered bacterial biosensor for detecting heavy metal ions, a common co-contaminant with pesticides [3] [4].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Engineered Chassis Cells (e.g., E. coli): Contain genetic circuit for sensing and reporting.

- Selection Antibiotic: Maintains plasmid stability in culture.

- Inducer/Analyte Standard: Pure standard for calibration (e.g., Cd²⁺ solution).

- Growth Media (e.g., LB Broth): Supports cell growth and maintenance.

- Multi-well Plate (e.g., 96-well): Platform for high-throughput assay.

- Microplate Reader: Instrument to quantify optical signals (fluorescence/absorbance).

Procedure:

- Cell Culture: Inoculate a culture of the engineered biosensor strain in a growth medium containing the appropriate antibiotic to maintain the sensor plasmid. Grow overnight to stationary phase.

- Sensor Induction: Dilute the overnight culture in fresh, pre-warmed medium. Aliquot the diluted cells into a multi-well plate. Add the sample or a series of standard solutions containing the target analyte (e.g., Cd²⁺) to the wells. Include a negative control (no analyte) and a positive control if available.

- Incubation and Signal Development: Incubate the plate at the optimal temperature for the chassis cell with shaking, typically for several hours to allow for gene expression and signal development.

- Signal Measurement: Place the plate in a microplate reader. Measure the fluorescence intensity (e.g., excitation/emission for GFP) or absorbance of the culture in each well.

- Data Analysis: Subtract the signal from the negative control (background) from all samples. Plot the corrected signal against the known concentrations of the standard to generate a calibration curve. The concentration of the analyte in unknown samples can be determined by interpolating from this curve.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The development and deployment of biosensors require a suite of specialized reagents and materials. The following table details key solutions and their functions in biosensor research.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Biosensor Development

| Reagent/Material | Function/Explanation | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|

| Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) | Key biorecognition element; its inhibition by OPs/carbamates is the basis of detection. | Enzyme Inhibition Biosensors [1] [5] |

| Glucose Oxidase (GOx) | Model enzyme for biosensor development; catalyzes glucose oxidation. | Medical Diagnostics, Biosensor Fundamentals [1] [7] |

| Transcription Factors (e.g., MerR, CadR) | Natural or engineered proteins that bind specific analytes and regulate gene expression. | Whole-Cell Biosensor Sensing Elements [3] [4] |

| Reporter Proteins (e.g., GFP, RFP) | Generate a measurable optical signal (fluorescence) upon gene expression. | Whole-Cell Biosensor Reporting Elements [3] [8] |

| Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) | Synthetic, stable polymers with cavities complementary to a target molecule. | Biomimetic Recognition Element in Sensors [9] |

| Nanozymes (e.g., CuO NPs, SACe-N-C) | Nanomaterials with enzyme-like catalytic activity; offer enhanced stability. | Stable Alternatives to Natural Enzymes [5] |

| Carbon Nanotubes / Graphene | Enhance electrical conductivity and provide a high surface area for immobilization. | Electrochemical Transducer Enhancement [1] [10] |

| Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide (NAD+) | Coenzyme required for the activity of many dehydrogenase enzymes. | Enzyme-Based Electrochemical Gas Sensors [6] |

Enzymatic biosensors are analytical devices that integrate a biological enzyme as the primary recognition element with a physicochemical transducer to produce a measurable signal proportional to the concentration of a target analyte [11]. The defining characteristic of these biosensors is their reliance on the specific catalytic reaction mediated by the immobilized enzyme, which selectively converts the target substrate into a measurable product [12]. This catalytic mechanism stands in sharp contrast to affinity-based biosensors (e.g., immunosensors or DNA sensors) that depend on binding events without substrate conversion. The exceptional specificity of enzymatic biosensors originates from the lock-and-key relationship between the enzyme's active site and its specific substrate, enabling accurate detection even within complex sample matrices like environmental water, food products, or biological fluids [12] [13].

In the broader context of pesticide detection research, enzymatic biosensors represent a sophisticated alternative to whole-cell biosensing systems. While whole-cell biosensors (utilizing algae, cyanobacteria, or bacteria) often detect herbicides through non-specific inhibition of photosynthetic electron transport in photosystem II (PSII), enzymatic biosensors typically employ enzyme inhibition principles or occasionally direct substrate conversion for specific pesticide quantification [14]. This targeted approach offers potentially higher specificity for individual pesticides or well-defined pesticide classes, though it may sacrifice the broad-spectrum detection capability of some whole-cell systems that respond to multiple pesticides sharing a common inhibition mechanism [14] [15].

Core Mechanism and Signal Transduction

Fundamental Operating Principle

The operational mechanism of enzymatic biosensors follows a consistent sequence: (1) diffusion of the target analyte (substrate) to the biologically active surface, (2) specific recognition and catalytic conversion of the substrate by the immobilized enzyme, (3) transduction of the biochemical signal into a measurable physical signal, and (4) signal processing and readout [13]. The catalytic reaction typically generates or consumes a detectable species (electroactive products, protons, light, or heat), with the reaction rate being proportional to the substrate concentration according to Michaelis-Menten kinetics [12].

The mechanism of signal generation varies significantly based on the transducer type. Electrochemical biosensors dominate the field due to their high sensitivity, ease of miniaturization, and cost-effectiveness [12] [16]. These are frequently categorized into amperometric, potentiometric, conductometric, and impedimetric systems. Optical biosensors represent another major category, capitalizing on phenomena such as absorbance, fluorescence, chemiluminescence, or surface plasmon resonance to detect the products of enzymatic reactions [12].

Enzyme Inhibition-Based Detection for Pesticides

A substantial segment of enzymatic biosensors for pesticide detection operates on the principle of enzyme inhibition rather than direct substrate conversion [14]. In this configuration, the measurable signal (typically the rate of substrate conversion by the enzyme) decreases upon exposure to pesticides that act as enzyme inhibitors. The degree of inhibition correlates with the pesticide concentration, enabling quantification [14] [13]. This approach is particularly relevant for detecting organophosphate and carbamate insecticides, which are potent acetylcholinesterase (AChE) inhibitors, as well as herbicides that target specific plant enzymes [14].

Key advantages of inhibition-based biosensors include their ability to detect pesticides that are not direct enzyme substrates and their compatibility with a wide range of transducer types. However, a significant challenge is the limited specificity, as different pesticides may inhibit the same enzyme, making it difficult to identify the specific inhibitor in a sample [14]. Additionally, the detection requires a reversible inhibition mechanism to allow biosensor regeneration, or single-use configurations must be employed.

Table 1: Common Enzyme Classes Used in Biosensors and Their Detection Mechanisms

| Enzyme Class | Example Enzymes | Target Analytes | Detection Mechanism | Application in Pesticide Detection |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oxidoreductases | Glucose Oxidase, Polyphenol Oxidase, Tyrosinase | Glucose, Phenolic compounds, Catechol | Amperometric detection of electron transfer via mediators or direct electron transfer | Detection of herbicides like atrazine via inhibition of tyrosinase [12] [14] |

| Hydrolases | Acetylcholinesterase, Alkaline Phosphatase, Organophosphohydrolase | Acetylcholine, Organophosphates | Potentiometric detection of pH change or amperometric detection of electroactive products | Direct detection of organophosphates or inhibition-based detection [14] [13] |

| Lyases | 5-enolpyruvylshikimate-3-phosphate synthase (EPSPS) | Glyphosate | Optical or electrochemical detection of reaction products | Direct detection of glyphosate herbicide [14] |

Experimental Implementation and Methodologies

Biosensor Fabrication Protocol: Enzyme Immobilization

A critical determinant of enzymatic biosensor performance is the method employed for enzyme immobilization on the transducer surface. The immobilization strategy must preserve enzymatic activity while ensuring strong attachment and stability. A representative protocol based on recent research for constructing a glucose biosensor using glucose oxidase (GOx) immobilized in a polyacrylic acid/carbon nanotube (PAA/CNT) composite is detailed below [16]:

Materials Required:

- Pt disk electrodes (3 mm diameter) or screen-printed Pt electrodes

- Carboxylated single-walled carbon nanotubes (1.0-3.0 at % carboxylic acid)

- Glucose oxidase (GOx) from Aspergillus niger

- Polyacrylic acid (PAA, average M_r ~250,000)

- Sodium phosphate buffer (0.1 M, pH 7.0)

- Polishing suspension (0.4 μm alumina powder)

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Electrode Pretreatment: Polish the Pt disk electrode on a pad soaked with alumina suspension to create a fresh, clean surface. Rinse thoroughly with deionized water.

CNT Layer Formation: Apply 5 μL of a homogenous, ultrasonicated CNT suspension (5 mg mL⁻¹ in deionized water) onto the Pt disk surface. Allow to dry completely, forming a thin, adherent, nano-porous CNT film.

Enzyme Loading: Apply 5 μL of GOx solution (20 mg mL⁻¹ in 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.0) onto the CNT-modified electrode. Dry at room temperature, allowing the enzyme to adsorb into the CNT matrix.

Polymeric Encapsulation: Apply 5 μL of diluted PAA suspension (0.5 mg mL⁻¹) over the GOx-CNT layer and dry. This PAA topcoat serves as a protective barrier against enzyme leakage while permitting substrate diffusion.

Conditioning: Immerse the completed biosensor in stirred 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) for 30 minutes to remove loosely attached components.

This fabrication approach exemplifies a simple "drop-and-dry" immobilization technique that combines adsorption (enzyme onto CNTs) with entrapment (behind a PAA membrane), resulting in biosensors with excellent operational stability and sensitivity down to 10 μM glucose [16].

Amperometric Measurement Protocol

Amperometric detection represents one of the most common transduction methods for enzymatic biosensors, particularly for pesticide detection [14]. The following protocol describes the measurement setup for a typical oxidase-based biosensor:

Apparatus and Reagents:

- Potentiostat connected to a three-electrode electrochemical cell

- Biosensor as working electrode (WE)

- Ag/AgCl reference electrode (RE)

- Pt wire counter electrode (CE)

- 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) as electrolyte

- Standard solutions of the target analyte

Measurement Procedure:

Instrument Setup: Connect the biosensor as the working electrode in the three-electrode cell configuration. Set the working electrode potential to the optimal value for detecting the enzymatic product (e.g., +0.6 V vs. Ag/AgCl for anodic detection of H₂O₂ generated by oxidase enzymes) [16].

Baseline Establishment: Immerse the electrode system in stirred buffer and apply the set potential until a stable baseline current is established.

Standard Additions: Introduce successive aliquots of standard analyte solutions into the cell under continuous stirring. The enzyme catalyzes the conversion of the analyte, producing an electroactive product (e.g., H₂O₂ from glucose oxidase reaction).

Current Measurement: Record the steady-state oxidation current resulting from the electrochemical detection of the enzymatic product at each analyte concentration.

Calibration Curve: Plot the measured current (or current change) against analyte concentration to generate a calibration curve for quantitative analysis.

For inhibition-based pesticide detection, the procedure is modified to include:

Initial Activity Measurement: Determine the baseline enzyme activity by measuring the current response to a fixed concentration of the enzyme's substrate.

Inhibition Phase: Expose the biosensor to the sample containing the pesticide inhibitor for a fixed incubation period.

Residual Activity Measurement: Re-measure the enzyme activity using the same substrate concentration after inhibition.

Inhibition Calculation: Calculate the percentage inhibition as [(I₀ - Iᵢ)/I₀] × 100%, where I₀ is the initial current and Iᵢ is the current after inhibition. The percentage inhibition is then correlated with pesticide concentration using a calibration curve.

Performance Data and Comparative Analysis

Analytical Performance of Representative Enzymatic Biosensors

The analytical performance of enzymatic biosensors varies significantly based on the enzyme, immobilization method, transducer type, and target analyte. The following table summarizes performance metrics for representative enzymatic biosensors reported in recent literature, with particular emphasis on systems applicable to pesticide detection.

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Representative Enzymatic Biosensors

| Target Analyte | Enzyme Used | Transducer Type | Linear Range | Detection Limit | Application Demonstrated |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phenolic Compounds | Polyphenol Oxidase (PPO) | Electrochemical | N/A | 0.13 μM (for catechin) | Food quality control in kombucha samples [12] |

| D-2-hydroxyglutaric acid (D2HG) | D-2-hydroxyglutarate Dehydrogenase (D2HGDH) | Amperometric with electron mediator | 0.5-120 μM | N/A | Detection in fetal bovine serum and artificial urine [12] |

| Catechol | Tyrosinase (TYR) | Personal Glucose Meter (PGM) adaptation | N/A | N/A | TYR activity and inhibitor detection [12] |

| Atrazine | Acetolactate Synthase (ALS) | Heterogeneous assay | N/A | N/A | Herbicide detection [14] |

| Glyphosate | 5-enolpyruvylshikimate-3-phosphate synthase (EPSPS) | Heterogeneous assay | N/A | N/A | Herbicide detection [14] |

Comparative Analysis: Enzymatic vs. Whole-Cell Biosensors for Pesticide Detection

When evaluating biosensing platforms for pesticide detection, understanding the relative advantages and limitations of enzymatic versus whole-cell approaches is essential for selecting the appropriate technology for specific applications.

Table 3: Enzymatic vs. Whole-Cell Biosensors for Pesticide Detection

| Parameter | Enzymatic Biosensors | Whole-Cell Biosensors |

|---|---|---|

| Specificity | High specificity for target enzyme substrates or inhibitors; can distinguish between closely related chemical structures [14] | Broader specificity; often detect entire classes of pesticides sharing a mode of action (e.g., PSII inhibitors) [14] [15] |

| Detection Mechanism | Direct enzyme inhibition or substrate conversion | Typically inhibition of photosynthetic electron transport or metabolic pathways [14] |

| Response Time | Minutes to tens of minutes | Can be slower (tens of minutes to hours) due to diffusion barriers and complex physiological responses [14] |

| Lifespan & Stability | Moderate stability (days to weeks); enzyme activity degrades over time | Can be more robust; living cells can maintain functionality longer under proper conditions [14] |

| Complexity | Relatively simple system with single biological component | Complex system with multiple interacting components and metabolic pathways [14] |

| Primary Applications in Pesticide Detection | Detection of specific herbicides (e.g., atrazine, glyphosate) and insecticides (organophosphates, carbamates) via enzyme inhibition [14] | Broad-spectrum detection of photosynthetic inhibitors (e.g., diuron, atrazine) and other metabolic disruptors [14] [15] |

| Key Advantage | High specificity, well-defined mechanism, rapid response for certain systems | Broader detection capability, can indicate biological availability and toxicity [14] |

| Principal Limitation | Limited to detecting compounds that interact with specific enzymes; enzyme stability issues | Less specific, longer response times, complex maintenance requirements [14] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful development and implementation of enzymatic biosensors requires specific materials and reagents that ensure optimal performance, stability, and reproducibility. The following toolkit compiles essential components referenced across multiple studies.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Enzymatic Biosensor Development

| Category/Reagent | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enzyme Materials | Glucose Oxidase, Tyrosinase, Polyphenol Oxidase, Acetylcholinesterase, Alkaline Phosphatase | Biological recognition element; provides specificity through catalytic action or inhibition | Select based on target analyte; consider purity, specific activity, and inhibition characteristics [12] [14] [16] |

| Electrode Materials | Pt disk electrodes, Screen-printed electrodes (SPE), Gold electrodes, Carbon-based electrodes | Signal transduction platform; serves as base for enzyme immobilization and electron transfer | Screen-printed electrodes enable mass fabrication and disposable applications [12] [16] |

| Nanomaterials | Carbon nanotubes (CNTs), Graphene, Gold nanoparticles, Two-dimensional materials | Enhance surface area, improve electron transfer efficiency, facilitate enzyme immobilization | CNTs create nanoporous films for high enzyme loading; functionalized CNTs enable covalent immobilization [16] |

| Immobilization Matrices | Polyacrylic acid (PAA), Chitosan, Polyaniline, Nafion, Self-assembled monolayers (SAMs) | Entrap and stabilize enzymes on transducer surface; prevent enzyme leakage while allowing substrate diffusion | PAA forms protective topcoats; optimal concentration critical (0.5 mg/mL in drop-and-dry methods) [16] |

| Electron Mediators | Methylene Blue, Ferrocene derivatives, Hexacyanoferrate, Quinones | Shuttle electrons between enzyme active site and electrode surface; enhance signal intensity | Particularly important for oxidoreductases without direct electron transfer capability [12] |

| Buffer Systems | Phosphate buffer, Tris buffer, Acetate buffer | Maintain optimal pH for enzyme activity; provide consistent ionic environment | Typical concentration 0.1 M, pH optimized for specific enzyme (e.g., pH 7.0 for many oxidases) [16] |

Enzymatic biosensors represent a sophisticated technology platform that leverages the exceptional specificity of biological catalysis for analytical detection. Their core mechanism, centered on enzyme-substrate recognition and catalytic conversion, provides fundamental advantages in specificity and design flexibility compared to whole-cell alternatives. In pesticide detection research, enzymatic biosensors offer the potential for targeted detection of specific herbicide and insecticide classes through well-defined inhibition mechanisms, complementing the broader-spectrum detection capabilities of whole-cell systems.

Despite significant advances, challenges remain in enhancing enzyme stability, improving immobilization techniques, and expanding the repertoire of detectable pesticides. Future directions will likely focus on integrating novel nanomaterials to enhance sensitivity, developing multiplexed platforms for simultaneous detection of multiple pesticides, and creating more robust immobilization strategies for field-deployable devices. As these technologies mature, enzymatic biosensors are poised to play an increasingly important role in environmental monitoring, food safety, and public health protection through their unique combination of biological specificity and analytical precision.

The detection of pesticide residues represents a critical challenge in ensuring environmental safety and food security. Within this field, two principal biosensing architectures have emerged: enzymatic biosensors and whole-cell biosensors. While enzymatic biosensors utilize isolated enzymes as recognition elements, whole-cell biosensors employ living microorganisms as integrated sensing systems. The fundamental distinction lies in their biological complexity; enzymatic biosensors rely on single enzyme-target interactions, whereas whole-cell biosensors exploit the full metabolic and regulatory capabilities of living cells [14] [17].

For pesticide detection, enzymatic biosensors typically function on the principle of enzyme inhibition. Neurotoxic insecticides such as organophosphates and carbamates are detected through their inhibition of acetylcholinesterase (AChE), while herbicides like atrazine and diuron are detected via their inhibition of photosystem II (PSII) or enzymes such as tyrosinase [14] [17]. These systems offer direct measurement capabilities but often lack specificity, as multiple compounds can inhibit the same enzyme. Moreover, they require enzyme purification and stabilization, increasing complexity and cost [14].

In contrast, whole-cell biosensors leverage cellular transcription factors and genetic circuits to detect target compounds, converting this recognition into measurable signals through synthetic biology approaches. These systems benefit from inherent amplification through gene expression, self-replication of sensing components, and the protective intracellular environment that enhances stability [3]. This architectural comparison frames the subsequent detailed examination of whole-cell biosensor design, which offers distinct advantages for implementation in pesticide monitoring programs.

Table 1: Core Architectural Comparison Between Biosensor Types for Pesticide Detection

| Feature | Enzymatic Biosensors | Whole-Cell Biosensors |

|---|---|---|

| Recognition Element | Purified enzymes (e.g., AChE, tyrosinase, PSII) | Transcription factors, riboswitches, cellular metabolic pathways |

| Detection Principle | Mainly enzyme inhibition | Ligand-induced gene expression |

| Specificity | Lower - multiple inhibitors affect same enzyme | Higher - can be engineered for specific targets |

| Production Cost | Higher - requires enzyme purification | Lower - cells self-replicate all components |

| Stability | Moderate - enzymes require stabilization | High - intracellular environment provides stability |

| Sample Pre-treatment | Often required | Minimal due to cellular anti-interference capabilities |

| Multi-analyte Detection | Challenging | Enabled through complex genetic circuits |

Core Architectural Components of Whole-Cell Biosensors

The architecture of synthetic biological whole-cell biosensors comprises three fundamental components: sensing elements that detect target substances, genetic circuits that process this information, and reporting elements that generate measurable outputs. This modular organization enables the engineering of sophisticated detection systems for diverse pesticides and other contaminants [3].

Sensing Elements: Transcription Factors and Riboswitches

Sensing elements serve as the molecular recognition interface between the target analyte and the biosensor system. In whole-cell biosensors, these primarily consist of transcription factors and riboswitches that undergo conformational changes upon binding specific ligands [3].

Transcription factors are proteins that bind to specific DNA sequences upstream of genes, regulating their transcription. In biosensor design, the transcription factor and its corresponding inducible promoter sequence are identified and placed upstream of a reporter gene. When the target substance is present, it binds to the transcription factor, altering its ability to bind the promoter region and thereby activating or repressing transcription of the reporter gene. For pesticide detection, transcription factors can be engineered to recognize specific compounds. For instance, the TtgR transcription factor from Pseudomonas putida has been utilized to develop biosensors responsive to various flavonoids and bioactive compounds [18]. More than 300 prokaryotic transcription factors have been discovered, with databases such as CollecTF, P2TFA, porTF, and portTF providing resources for identifying factors that recognize specific targets [3].

Riboswitches represent another class of sensing elements. These are untranslated regions of mRNA containing sequences with specific conformations that can bind target molecules. When a riboswitch undergoes a conformational change upon ligand binding, it exposes or hides the ribosome binding sites of mRNA, thereby activating or inhibiting the translation process. This provides a direct means of regulating gene expression at the translational level in response to target analytes [3].

Reporting Elements: From Fluorescence to Gas Production

Reporting elements convert the internal recognition event into a detectable signal. The most common reporting elements are optical, particularly fluorescent proteins such as enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP) and red fluorescent proteins. These provide visual signals that can be quantified with high sensitivity using fluorometers [3] [18]. For example, in the TtgR-based biosensor system, eGFP serves as the reporter, with fluorescence intensity correlating with the concentration of target flavonoids [18].

Beyond fluorescence, other reporting mechanisms include gas production, colorimetric changes, and electrochemical signals. The choice of reporter depends on the application context; for instance, field-deployable devices may benefit from visual color changes, while laboratory settings can utilize more sophisticated fluorescent measurements [3].

Chassis Cells: Selection and Optimization

Chassis cells provide the cellular environment in which the biosensor components operate. Escherichia coli is frequently used due to its well-characterized genetics and ease of manipulation, as demonstrated in biosensors for heavy metals and flavonoids [4] [18]. Other microorganisms such as yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) have also been employed, particularly for eukaryotic protein processing capabilities [3].

The selection of appropriate chassis cells is critical for biosensor performance, as cellular metabolism, membrane permeability, and background activity can all influence signal-to-noise ratios and detection limits. In some cases, chassis cells are engineered to enhance performance by reducing background expression or improving substrate uptake [3] [4].

Genetic Circuit Design: From Simple Switches to Complex Logic

Genetic circuits form the information processing core of whole-cell biosensors, linking sensing to reporting through programmed gene expression. These circuits have evolved from simple inducible systems to sophisticated networks incorporating amplification, logic operations, and feedback control.

Basic Circuit Configurations

The simplest genetic circuit consists of a sensing element directly controlling a reporter gene. For example, a transcription factor responsive to a target pesticide regulates the expression of a fluorescent protein. While straightforward, such designs often suffer from limited sensitivity and high background noise [3].

More advanced configurations incorporate signal amplification. In the LC100-2 biosensor for ultra-trace cadmium detection, the LacI protein serves as both a signal amplifier and a negative feedback module. The circuit employs a dual-input promoter (PT7-cadO-lacO-cadO) regulated by both Cd²⁺ and IPTG, with the structure "CadR-PJ23100-PT7-cadO-lacO-cadO-mRFP1-LacI" [4]. This design achieved a remarkable detection limit of 0.00001 nM for Cd²⁺, with sensitivity 3748 times greater than the basic construct [4].

Figure 1: Genetic Circuit Architecture with Signal Amplification and Feedback

Engineering Specificity and Sensitivity

Transcription factor engineering enables the customization of biosensor specificity and sensitivity. Several molecular approaches have been successfully employed:

Truncation: Shortening transcription factors to optimize performance. Tao et al. optimized specificity for cadmium and mercury ions by truncating 10 and 21 amino acids from the C-terminal of the CadR transcription factor [3].

Chimerism: Combining target recognition domains from one transcription factor with gene expression regulation domains from another. Mendoza et al. created a mercury-specific biosensor by replacing the gold ion recognition domain of GolS77 with the mercury ion recognition domain of MerR [3].

Functional Domain Mutation: Site-specific mutation of functional domains. Kasey et al. constructed a saturated mutation library of all five amino acid sites within the recognition domain of the MphR transcription factor, screening for mutants with enhanced specificity and sensitivity for macrolides [3].

Whole-Protein Mutation: Random mutation of the entire transcription factor protein. Chong et al. used error-prone PCR to introduce random mutations into DmpR genes, screening for transcription factors with improved performance and specific response to organophosphorus compounds [3].

De Novo Design: Creating entirely novel transcription factors. Chang et al. proposed a strategy for designing transcription factors from scratch by fusing single-domain antibodies to monomer DNA binding domains, creating sensors for new target ligands [3].

These engineering approaches have been successfully applied to pesticide detection systems. For instance, engineered TtgR variants with modified ligand-binding pockets demonstrated altered sensing profiles for flavonoids, enabling the development of biosensors with tailored specificity for compounds like resveratrol and quercetin [18].

Table 2: Transcription Factor Engineering Strategies for Enhanced Biosensor Performance

| Engineering Strategy | Mechanism | Application Example | Performance Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Truncation | Shortening transcription factor length | CadR TF with 10-21 amino acids removed from C-terminal | Enhanced specificity for Cd²⁺ and Hg²⁺ over Zn²⁺ |

| Chimerism | Combining domains from different TFs | MerR recognition domain fused to GolS77 regulatory domain | Converted gold sensor to mercury sensor |

| Functional Domain Mutation | Site-specific mutation of binding pocket | Saturated mutagenesis of MphR's five binding amino acids | Increased specificity and sensitivity for macrolides |

| Whole-Protein Mutation | Random mutation throughout protein | Error-prone PCR on DmpR genes | Improved induced expression level for organophosphorus |

| De Novo Design | Creating novel TFs from scratch | Fusion of antibodies to DNA-binding domains | Transcription factors for new target ligands |

Experimental Protocols for Whole-Cell Biosensor Construction and Implementation

The development and application of whole-cell biosensors follows a systematic experimental pipeline from genetic construction to performance validation. Below are detailed protocols for key processes in biosensor implementation.

Biosensor Assembly and Transformation Protocol

Materials:

- E. coli BL21(DE3) or DH5α competent cells (chassis cells)

- Plasmid vectors (e.g., pCDF-Duet for sensing elements, pZnt-eGFP for reporting)

- Restriction enzymes (NdeI, NotI, BglII, XbaI)

- Ligase enzyme

- PCR components: template DNA, primers, Hotstar Taq polymerase, PfuTurbo for mutagenesis

- LB media: tryptone, yeast extract, sodium chloride

- Selection antibiotics [18]

Procedure:

- Genetic Element Amplification: Amplify transcription factor genes (e.g., ttgR) and corresponding operator sequences (e.g., PttgABC) via PCR using genomic DNA from source organisms (e.g., Pseudomonas putida) as template [18].

Plasmid Construction: Digest plasmid vectors and amplified DNA fragments with appropriate restriction enzymes (NdeI/NotI for sensing elements, BglII/XbaI for reporter elements). Purify fragments using gel elution kits and ligate using ligase enzyme [18].

Transformation: Introduce constructed plasmids into E. coli chassis cells via heat shock or electroporation. Plate transformed cells on LB agar containing appropriate selection antibiotics [18].

Colony Screening: Pick individual colonies, culture in liquid LB media with antibiotics, and verify plasmid construction through DNA sequencing [18].

Biosensor Performance Assay Protocol

Materials:

- Biosensor cell cultures

- Target analytes (pesticides, flavonoids, heavy metals)

- Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) for stock solutions

- Fluorescence spectrometer (e.g., FluoroMate FC-2)

- Spectrophotometer for OD600 measurements [18]

Procedure:

- Culture Preparation: Inoculate biosensor cells from glycerol stocks into LB media with appropriate antibiotics. Grow overnight at 37°C with shaking at 250 rpm [18].

Exposure Experiment: Dilute overnight cultures in fresh media and grow until OD600 reaches approximately 0.3. Add target compounds (0.005–5 mM range) dissolved in DMSO. Include DMSO-only controls [18].

Signal Measurement: Incubate exposed cultures for 1-3 hours. Measure fluorescence intensity using excitation at 480 nm and emission at 510 nm. Simultaneously measure OD600 to normalize for cell density [18].

Data Analysis: Calculate induction coefficient as (eGFP intensity with chemical exposure)/(eGFP intensity without chemical exposure), with compensation for OD600 values. Generate dose-response curves by plotting induction coefficient against analyte concentration [18].

Specificity and Cross-Reactivity Testing Protocol

Materials:

- Biosensor cell cultures

- Panel of structurally related and unrelated compounds

- Positive and negative control compounds [18]

Procedure:

- Compound Panel Preparation: Prepare stock solutions of test compounds at maximum concentration (e.g., 5 mM) in appropriate solvents [18].

Exposure and Measurement: Expose biosensor cells to each compound individually using the biosensor performance assay protocol. Include known activators as positive controls and solvent-only as negative controls [18].

Specificity Calculation: Calculate response ratios for each compound relative to the positive control. Compounds eliciting less than 10-15% of the positive control response are typically considered non-cross-reactive [18].

Computational Validation: Perform in silico docking studies to understand structural basis of specificity. Use molecular modeling software to simulate transcription factor-ligand interactions and identify key binding residues [18].

Advanced Applications: Multi-Analyte Detection and Field Deployment

Whole-cell biosensors have evolved beyond single-analyte detection to incorporate sophisticated multi-analyte capabilities and field-deployable formats. These advancements address critical needs in pesticide monitoring where multiple contaminants may coexist and where on-site analysis provides significant advantages over laboratory-based methods.

Multi-Analyte Detection Systems

The integration of artificial neural networks (ANNs) with biosensor arrays enables the discrimination of multiple insecticides in complex mixtures. This approach utilizes the varying inhibition patterns of different acetylcholinesterase (AChE) variants toward organophosphates and carbamates. In one implementation, four AChE biosensors based on enzymes from different sources (electric eel, bovine erythrocytes, rat brain, and Drosophila melanogaster) were combined with ANN analysis to simultaneously detect paraoxon and carbofuran in mixtures with concentrations of 0–20 μg L⁻¹, achieving prediction errors of 0.9 μg L⁻¹ for paraoxon and 1.4 μg L⁻¹ for carbofuran [17].

Further refinement using genetically engineered AChE variants from Drosophila melanogaster (wild-type and mutants Y408F, F368L, F368H, and F368W) improved resolution for binary paraoxon and carbofuran mixtures at lower concentrations (0–5 μg L⁻¹), with prediction errors of 0.4 μg L⁻¹ for paraoxon and 0.5 μg L⁻¹ for carbofuran. Remarkably, this system was adapted to discriminate between two organophosphates (malaoxon and paraoxon) in mixtures, demonstrating versatility within the same insecticide class [17].

Figure 2: Multi-Analyte Detection System Using Biosensor Arrays and ANN

Field-Deployable Formats and Commercial Applications

Whole-cell biosensors have been implemented in various field-deployable formats including test strips, kits, and increasingly in wearable devices such as masks, hand rings, and clothing [3]. These formats leverage the key advantages of whole-cell systems: minimal sample preprocessing, stability in variable environmental conditions, and visual signal outputs that don't always require sophisticated instrumentation.

For photosynthetic herbicide detection, biosensors based on algae, cyanobacteria, thylakoids, or chloroplasts have been developed, primarily monitoring inhibition of photosynthetic electron transport through amperometric measurements or chlorophyll fluorescence [14]. These systems are particularly amenable to field deployment as they can utilize visual color changes or simple fluorometers for detection.

The integration of whole-cell biosensors into microfluidic devices and lab-on-a-chip systems further enhances their field applicability by enabling automated sample processing and multiplexed analysis. Such integrated systems represent the cutting edge of biosensor technology for environmental monitoring [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The construction and implementation of whole-cell biosensors requires specialized reagents and materials. The following table details essential components for biosensor development, particularly focused on pesticide detection applications.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Whole-Cell Biosensor Development

| Reagent/Material | Specification/Example | Function in Biosensor Development |

|---|---|---|

| Chassis Cells | E. coli BL21(DE3), DH5α strains | Host organisms for genetic circuit implementation |

| Plasmid Vectors | pCDF-Duet, pZnt-eGFP | Carriers for sensing and reporter genetic elements |

| Restriction Enzymes | NdeI, NotI, BglII, XbaI | Molecular tools for plasmid construction |

| Polymerases | Hotstar Taq (amplification), PfuTurbo (mutagenesis) | DNA amplification and engineering |

| Culture Media | Lysogeny Broth (tryptone, yeast extract, NaCl) | Cell cultivation and maintenance |

| Target Compounds | Flavonoids, pesticides, heavy metal ions | Analytes for biosensor validation |

| Solvents | Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) | Preparation of analyte stock solutions |

| Detection Instrumentation | Fluorescence spectrometer | Measurement of reporter signals |

| Engineering Templates | Genomic DNA from Pseudomonas putida | Source of natural transcription factors |

| Selection Agents | Appropriate antibiotics | Maintenance of plasmid integrity |

Whole-cell biosensors represent a sophisticated architecture for pesticide detection that leverages cellular regulatory mechanisms through synthetic biology. Their modular design—comprising sensing elements, genetic circuits, and reporting systems—enables customization for diverse detection scenarios. When compared to enzymatic biosensors, whole-cell systems offer advantages in specificity engineering, self-replication, reduced production costs, and robustness in complex sample matrices.

The future development of whole-cell biosensors will likely focus on enhancing sensitivity through improved genetic circuit design, expanding the range of detectable pesticides through transcription factor engineering, and creating increasingly field-deployable formats for on-site monitoring. As synthetic biology tools advance, the integration of more complex computational capabilities within living cells may further blur the distinction between biological sensors and analytical instruments, creating powerful new tools for environmental protection and food safety.

This technical guide examines the core performance drivers of enzymatic and whole-cell biosensors within pesticide research. It provides a comparative analysis of specificity, sensitivity, and signal transduction mechanisms, underpinned by experimental protocols and quantitative data. Enzymatic biosensors typically achieve higher specificity through inhibitor-based recognition, whereas whole-cell systems offer broader biological relevance by detecting photosynthetic inhibition. Advancements in chemical signal amplification, nanomaterials, and genetic engineering are pushing detection limits to sub-picomolar concentrations, enabling these biosensors to serve as rapid, cost-effective early-warning systems that complement traditional chromatographic methods [19] [14] [17].

Biosensor performance is quantifiably evaluated through three interdependent parameters: sensitivity, specificity, and the efficiency of signal transduction. Sensitivity defines the lowest detectable concentration of an analyte, often expressed as the limit of detection (LOD). Specificity refers to the biosensor's ability to distinguish the target analyte from other interfering substances in a complex sample matrix. Signal transduction encompasses the process of converting the biorecognition event into a quantifiable physical signal, such as an electrical current or optical change [19] [17].

In the context of pesticide detection, the choice between enzymatic and whole-cell biosensors fundamentally shapes these performance parameters. Enzymatic biosensors often exploit the direct inhibition of a purified enzyme (e.g., acetylcholinesterase for neurotoxic insecticides, tyrosinase for herbicides), providing a highly specific molecular interaction. In contrast, whole-cell biosensors typically utilize photosynthetic organisms (e.g., algae, cyanobacteria) or their subcellular components (e.g., thylakoids, chloroplasts) to detect compounds that inhibit photosystem II (PSII), offering a more holistic measure of toxicity but potentially sacrificing molecular specificity [14] [17].

Specificity in Biosensor Design

Specificity is engineered into the biological recognition element. For pesticide detection, the mode of action of the herbicide or insecticide directly informs the choice of biorecognition element.

Enzymatic Biosensors

These biosensors achieve specificity by utilizing enzymes that are known targets of pesticides.

- Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) Inhibition: This is the standard mechanism for detecting neurotoxic organophosphates (OP) and carbamates (CB). The enzyme's active site binds these inhibitors, leading to irreversible (OP) or reversible (CB) inactivation. The degree of inhibition correlates with pesticide concentration [17].

- Photosystem II (PSII) Enzymes: Enzymes like tyrosinase or peroxidase are used to detect herbicides like atrazine and diuron, which inhibit the photosynthetic electron transport chain by binding to the D1 protein in PSII [14] [17].

- Enhancement Strategies: To overcome cross-reactivity, researchers use arrays of biosensors featuring genetically engineered mutant enzymes with varying inhibitor sensitivities. Data from these arrays are processed with chemometric methods like artificial neural networks (ANNs) to resolve mixtures of insecticides, such as paraoxon and carbofuran [17].

Whole-Cell Biosensors

These biosensors trade some molecular specificity for biological relevance.

- PSII-Based Detection: Whole-cell biosensors primarily detect the gross physiological effect of herbicides that inhibit photosynthesis. They measure the decrease in chlorophyll fluorescence or photosynthetic oxygen evolution, which is a generic response to all PSII-inhibiting herbicides [14].

- Specificity Limitations: This approach is less specific than enzymatic inhibition, as any stressor affecting photosynthesis can produce a false positive. However, it provides a "biologically relevant" integrated response to toxicity, which is valuable as an early-warning signal [14] [17].

Table 1: Specificity Comparison of Biosensor Types for Common Pesticides

| Biosensor Type | Biorecognition Element | Target Herbicide Examples | Mechanism of Action | Specificity Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enzymatic | Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) | Paraoxon, Carbofuran | Inhibition of enzyme activity | High (Molecular-level) |

| Enzymatic | Tyrosinase, Peroxidase | Atrazine, Diuron | Inhibition of PSII-associated enzymes | High (Molecular-level) |

| Whole-Cell | Algae, Cyanobacteria | Atrazine, Diuron | Inhibition of photosynthetic activity | Moderate (Pathway-level) |

| Organelle-Based | Thylakoids, Chloroplasts | Atrazine, Diuron | Inhibition of electron transport in PSII | Moderate (Pathway-level) |

Sensitivity and Signal Transduction Mechanisms

Sensitivity is predominantly enhanced at the signal transduction step, where a single biorecognition event is amplified into a strong, detectable signal.

Signal Amplification Strategies

A key strategy for enhancing sensitivity is chemical signal amplification, which maximizes the signal output per binding event [19].

- Polymerization-Based Amplification: This method uses radical initiators conjugated to probe molecules. Upon target recognition, a polymerization reaction is triggered, growing a long-chain polymer (e.g., poly-HEMA) from monomer molecules. The polymer formation, detectable as opaqueness or a mass change, dramatically amplifies the initial signal, enabling detection limits as low as 1 fM for DNA and 2.19 fmol/spot for immunoassays [19].

- Nanocatalyst-Based Amplification: Nanomaterials like Au/Pt or porous Pt nanoparticles act as peroxidase mimics. When conjugated to detection probes, these catalysts drive the oxidation of chromogenic substrates (e.g., TMB), producing a intense color signal. This method has achieved detection limits of 3.1 pg/mL and 0.8 pg/mL in sandwich-type lateral flow immunoassays [19].

- Enzymatic Amplification: Directly inspired by ELISA, this approach conjugates enzymes to detection antibodies or probes. The enzyme catalyzes the repeated turnover of a substrate into a colored, fluorescent, or chemiluminescent product, leading to significant signal accumulation [19] [17].

Transduction Modalities

The physical method of signal detection is chosen based on the application and required sensitivity.

- Electrochemical (Amperometry): The most common method for enzymatic and whole-cell biosensors. It measures the electrical current generated from redox reactions, such as the oxidation of phenolic products from enzyme activity or the reduction of oxygen in photosynthetic systems. It is known for its high sensitivity and portability [14] [17].

- Optical: Includes fluorescence, chlorophyll fluorescence, and colorimetry. For whole-cell biosensors, the inhibition of photosynthesis is directly measured by the decrease in chlorophyll fluorescence. Fluorescence-based genetic biosensors like SweetTrac1 also transduce substrate binding into fluorescence intensity changes [14] [20].

- Piezoelectric: Measures changes in the resonance frequency of a crystal due to mass loading from binding events, but is less frequently used [17].

Table 2: Quantitative Performance of Selected Biosensors for Pesticide Detection

| Biosensor Design | Transduction Method | Target Analyte | Reported Limit of Detection (LOD) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AChE-based (Enzymatic) | Amperometry | Carbaryl, Phoxim | Low μg/L range | [17] |

| AChE Mutant Array + ANN | Amperometry | Paraoxon, Carbofuran | 0.4 - 1.6 μg/L | [17] |

| PSII-based (Algal, Whole-Cell) | Chlorophyll Fluorescence | Diuron | Varies by strain & setup | [14] |

| Thylakoid-based | Amperometry | Phenylurea derivatives | ~10⁻¹¹ M | [14] |

| Polymerization-based DNA sensor | Opaqueness | DNA Target | 1 fM | [19] |

| Nano-catalyst Immunoassay | Chromogenesis | Protein Antigen | 0.8 - 3.1 pg/mL | [19] |

Experimental Protocol: Acetylcholinesterase Inhibition Assay

This protocol is typical for detecting neurotoxic insecticides [17].

- Immobilization: The AChE enzyme is immobilized on the surface of an electrochemical transducer (e.g., a screen-printed carbon electrode).

- Baseline Measurement: The amperometric response is recorded after adding the substrate, acetylthiocholine. The enzymatic hydrolysis produces thiocholine, which is oxidized at the electrode, generating a measurable baseline current (I₀).

- Inhibition Step: The biosensor is incubated with the sample containing the pesticide inhibitor for a fixed time (e.g., 10-15 minutes).

- Measurement Step: The substrate is added again, and the new amperometric response (I₁) is measured. The enzyme inhibition is irreversible for OPs and reversible for CBs.

- Quantification: The percentage of inhibition is calculated as

% Inhibition = [(I₀ - I₁) / I₀] * 100. This value is correlated with pesticide concentration using a pre-established calibration curve.

Experimental Protocol: Photosynthetic Activity Measurement

This protocol is used for whole-cell and organelle-based biosensors detecting PSII inhibitors [14].

- Preparation: Algal cells, thylakoid membranes, or chloroplasts are immobilized on a transducer or held in a cuvette.

- Baseline Measurement: For amperometry, the baseline rate of photosynthetic oxygen evolution is measured under illumination. For optical methods, the baseline level of chlorophyll fluorescence (F₀) or the variable fluorescence (Fᵥ) is recorded.

- Exposure: The sample containing the herbicide is introduced to the system.

- Inhibition Measurement: The decrease in the rate of oxygen evolution or the quenching of chlorophyll fluorescence is measured over time.

- Quantification: The percentage inhibition of photosynthetic activity is calculated and correlated with herbicide concentration.

Visualization of Biosensor Workflows

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table details essential materials and their functions for developing and operating biosensors in pesticide research.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Biosensor Development

| Reagent / Material | Function in Biosensor | Specific Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) | Biological recognition element for neurotoxic insecticides (OPs, CBs). | Purified from electric eel, bovine erythrocytes, or genetically engineered Drosophila mutants for enhanced specificity [17]. |

| Tyrosinase / Peroxidase | Biological recognition element for herbicides inhibiting photosynthetic enzymes. | Detection of atrazine and diuron via enzyme inhibition assays [14] [17]. |

| Algal Cells / Cyanobacteria | Whole-cell biorecognition element for photosynthetic inhibitors. | Used in amperometric or fluorescence-based biosensors to detect PSII inhibitors like diuron [14]. |

| Thylakoid Membranes / Chloroplasts | Subcellular biorecognition element offering higher relevance than enzymes but simpler than whole cells. | Isolated from spinach or peas for amperometric detection of herbicides [14]. |

| Nanoparticles (Au/Pt, Porous Pt) | Signal amplification labels; act as nanocatalysts in chromogenic reactions. | Conjugated to antibodies or probes in lateral flow immunoassays to lower detection limits to pg/mL levels [19]. |

| Circularly Permuted GFP (cpsfGFP) | Core component of genetically encoded biosensors; transduces binding events into fluorescence. | Used in transporter biosensors like SweetTrac1 to monitor substrate transport in live cells [20]. |

| Chromogenic Substrates (TMB) | Enzyme substrates that produce a visible color change upon catalytic reaction. | Used in ELISA-style and nanocatalyst-based signal amplification systems [19] [17]. |

| Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) | Chemometric tool for data analysis to enhance specificity and resolve pesticide mixtures. | Used with arrays of AChE variants to discriminate between paraoxon and carbofuran in mixtures [17]. |

The selection between enzymatic and whole-cell biosensors for pesticide detection involves a fundamental trade-off between molecular specificity and biological relevance. Enzymatic biosensors, particularly those employing mutant enzymes and chemometric analysis, offer high specificity and sensitivity, making them ideal for identifying specific pesticide residues. Whole-cell biosensors provide a integrated measure of toxicity, valuable for environmental monitoring and rapid screening. Future advancements will likely focus on integrating these platforms with novel signal amplification strategies like polymerization and nanocatalysts, and sophisticated data modeling tools such as the OmicSense platform [21], to create robust, field-deployable devices that deliver actionable data for agricultural and public health protection.

Design and Deployment: Building and Applying Pesticide Biosensors

Enzyme Selection and Immobilization Techniques (e.g., Acetylcholinesterase for OPs)

The intensive use of pesticides in agriculture has created an urgent need for rapid, sensitive, and cost-effective monitoring tools to detect these toxic compounds in environmental and food samples [15]. While whole-cell biosensors leverage living microorganisms as the sensing element, enzymatic biosensors utilize isolated enzymes as their biorecognition component, offering distinct advantages including higher stability, faster response times, and often simpler operational requirements [14]. This technical guide focuses on the core aspects of developing effective enzymatic biosensors, with particular emphasis on enzyme selection and immobilization techniques, framed within the context of academic research comparing whole-cell versus enzymatic approaches.

Enzymatic biosensors function on the principle of detecting changes in enzyme activity upon interaction with a target analyte. For pesticide detection, this typically occurs through inhibition-based detection, where the pesticide molecule binds to the enzyme and suppresses its catalytic activity, or biocatalytic detection, where the enzyme directly converts the pesticide into a measurable product [22]. The success of these biosensors hinges critically on two fundamental parameters: the judicious selection of an appropriate enzyme with high sensitivity and specificity toward the target pesticides, and the implementation of an effective immobilization strategy that preserves enzymatic activity while ensuring operational stability [23].

Enzyme Selection for Pesticide Biosensors

The selection of an appropriate enzyme is the cornerstone of developing a sensitive and selective biosensor. The biorecognition element must demonstrate high affinity for the target analyte while maintaining stability under operational conditions.

Acetylcholinesterase for Organophosphate and Carbamate Detection

Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) is the most extensively utilized enzyme for detecting organophosphate (OP) and carbamate pesticides, which function as neurotoxins by inhibiting this essential enzyme in the nervous system [22]. The mechanism involves hydrolysis of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine; when OP or carbamate pesticides are present, they phosphorylate or carbamylate the active site of AChE, leading to enzyme inhibition. This inhibition is measured quantitatively, typically by monitoring the reduction in hydrolysis products of substrates like acetylthiocholine [24]. AChE-based biosensors effectively provide a "biologically relevant" detection method, as they directly measure the compound's toxicity mechanism.

The sensitivity of AChE-based biosensors varies significantly depending on the enzyme source. For instance, AChE from electric eel, human erythrocytes, or Drosophila melanogaster exhibits different inhibition patterns and sensitivity levels to various pesticides [22]. Genetic engineering has enabled the development of mutant AChE enzymes with enhanced sensitivity toward specific pesticide classes, thereby improving biosensor performance [22].

Other Enzymes for Herbicide and Broad-Spectrum Detection

Beyond AChE, several other enzymes play crucial roles in detecting different pesticide classes:

- Photosystem II (PSII) Components: Enzymes and photosynthetic complexes such as tyrosinase, peroxidase, and chloroplasts are utilized for detecting herbicide classes like triazines and phenylureas. These compounds inhibit the photosynthetic electron transport chain, particularly in PSII, which can be measured via amperometric detection of oxygen evolution or chlorophyll fluorescence [14].

- Organophosphorus Hydrolase (OPH): Unlike inhibition-based approaches, OPH functions biocatalytically by hydrolyzing various OP pesticides (e.g., paraoxon, methyl parathion) to produce p-nitrophenol, which is electrochemically measurable [22].

- Other Inhibitable Enzymes: Enzymes including alkaline phosphatase, urease, and laccase have been employed for detecting pesticides that specifically inhibit their activity, broadening the spectrum of detectable compounds [22].

Table 1: Key Enzymes for Pesticide Detection Biosensors

| Enzyme | Target Pesticide Classes | Detection Mechanism | Typical Substrates |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) | Organophosphates, Carbamates | Inhibition | Acetylthiocholine, Acetylcholine |

| Tyrosinase | Atrazine, Phenylureas | Inhibition | Phenolic Compounds |

| Peroxidase | Triazines, Phenols | Inhibition | Hydrogen Peroxide, Organic Peroxides |

| Organophosphorus Hydrolase (OPH) | Organophosphates | Biocatalysis | Paraoxon, Parathion |

| Alkaline Phosphatase | Various Herbicides | Inhibition | p-Nitrophenyl Phosphate |

| Photosystem II Complex | Triazines, Phenylureas | Inhibition (Photosynthetic) | Water (O₂ evolution measured) |

Enzyme Immobilization Techniques

Immobilization of enzymes onto transducer surfaces is critical for biosensor stability, reusability, and functionality. The chosen method significantly impacts enzyme orientation, activity retention, and operational lifetime.

Porous Silicon-Based Immobilization

Porous silicon (PSi) has emerged as an exceptional substrate for enzyme immobilization due to its high surface area, tunable pore morphology, and biocompatibility [24] [25]. The large internal surface area of PSi allows for high enzyme loading capacity, while the controllable pore geometry enables optimal enzyme confinement.

Physical Adsorption: This straightforward approach involves dropping enzyme solution onto the PSi surface and allowing physical adsorption through hydrophobic interactions and hydrogen bonding. Studies have demonstrated that AChE physically adsorbed on mesoporous silicon retained significant activity, with enhanced stability—maintaining 50% activity up to 90°C, reusability for three cycles, and a shelf-life of 44 days [24]. While simple to implement, physical adsorption may result in enzyme leaching over extended use.

Covalent Attachment: For enhanced stability, covalent immobilization prevents enzyme leaching. Two primary strategies have been developed for PSi functionalization:

Hydrosilylation Approach: Hydrogen-terminated PSi undergoes reaction with ω-alkenoic acid (e.g., undecylenic acid) to create acid-terminated surfaces (PSi-COOH). The carboxylic groups are then activated with N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) and N-ethyl-N'-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-carbodiimide (EDC) to form reactive succinimidyl esters, which subsequently react with amine groups on enzyme lysine residues to form stable amide bonds [25].

Silanization Approach: PSi surfaces are first hydroxylated in piranha solution, followed by silanization with 3-aminopropyltriethoxysilane (APTES) to form amine-terminated surfaces (PSi-NH₂). AChE is then attached through aminolysis with enzyme carboxylic acid groups, again using NHS/EDC chemistry [25].

Comparative studies indicate that the orientation and surface coverage of immobilized AChE differ between these methods, directly impacting enzymatic activity. Contact angle measurements revealed that hydrosilylated surfaces are more hydrophobic (75°), while APTES-silanized surfaces are more hydrophilic (42°), influencing enzyme orientation and active site accessibility [25].

Nanomaterial-Enhanced Immobilization

Incorporating nanomaterials into biosensor design has significantly improved performance characteristics. Noble metal nanoparticles (especially gold and silver), carbon nanotubes, graphene, and nanohybrids provide enhanced electrical conductivity, increased surface area, and improved enzyme stability [26]. These nanomaterials facilitate better enzyme loading, more efficient electron transfer in electrochemical biosensors, and can be functionalized with various groups for optimized enzyme binding.

Table 2: Comparison of Enzyme Immobilization Techniques

| Immobilization Method | Mechanism of Attachment | Advantages | Limitations | Stability Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Adsorption on PSi | Hydrophobic interactions, Hydrogen bonding | Simple procedure, Minimal enzyme modification, Cost-effective | Enzyme leaching over time, Random orientation | 50% activity retention at 90°C, Reusable for 3 cycles, 44-day shelf life [24] |

| Covalent (Hydrosilylation) | Amide bond formation via NHS/EDC | Stable attachment, Prevents enzyme leaching, Enhanced operational stability | Complex multi-step process, Requires surface chemistry expertise | Improved long-term stability, Controlled orientation |

| Covalent (Silanization) | Amide bond formation via NHS/EDC | Stable attachment, Hydrophilic surface properties | Requires surface oxidation, Potential for multilayer formation | Enhanced pH stability (broad pH 4-9) |

| Nanomaterial-Based | Various (adsorption, covalent) | Enhanced sensitivity, Larger surface area, Improved electron transfer | Higher cost, Complex characterization | Increased reusability cycles, Extended shelf life |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

AChE Immobilization on Porous Silicon via Physical Adsorption

Materials and Instrumentation:

- Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) from human erythrocytes or Electric eel

- P-type silicon wafers (resistivity 1-20 Ω·cm)

- Hydrofluoric acid (HF, 48%) electrolyte solution

- Ethanol, acetone, deionized water

- Acetylthiocholine iodide, DTNB (Ellman's reagent)

- Field emission scanning electron microscope (FE-SEM), FT-IR spectrometer

Protocol:

- Porous Silicon Fabrication: Cut silicon wafer into 1×1 cm² chips. Clean by ultrasonication in acetone for 5 minutes, rinse with deionized water, and dry with nitrogen gas. Create a back ohmic contact using silver paste. Electrochemically anodize the silicon wafer at a current density of 20 mA/cm² in HF electrolyte solution (HF:H₂O:C₂H₅OH = 1:1:2 v/v) for 30 minutes in dark conditions [24].

- Surface Characterization: Verify pore formation and morphology using FE-SEM. Typical pore sizes should range between 2-50 nm with porous layer thickness of 3-4 μm [24].

- Enzyme Immobilization: Apply 20 μL of AChE solution (0.03 units/mL) directly onto the PSi surface and allow to dry at room temperature. Optimize enzyme loading by testing volumes between 10-30 μL [24].

- Activity Assay: Assess immobilized AChE activity using Ellman's spectrophotometric method. Incubate the immobilized enzyme with acetylthiocholine iodide (substrate) and DTNB in Tris/HCl buffer (pH 8.0). Measure the yellow anion formation at 412 nm after 10 minutes incubation at 37°C [24] [25].

Covalent Immobilization of AChE via Hydrosilylation and Silanization

Materials: Additional to 4.1: Undecylenic acid, APTES, NHS, EDC, nitrogen gas supply

Hydrosilylation Protocol:

- Surface Preparation: Prepare hydrogen-terminated PSi as in step 1 of 4.1.

- Hydrosilylation Reaction: React fresh hydrogen-terminated PSi with 10% undecylenic acid in deoxygenated toluene under nitrogen atmosphere for 12-18 hours at room temperature to form PSi-COOH surfaces [25].

- Activation: Activate carboxylic groups with NHS (0.1 M) and EDC (0.2 M) in buffer for 1 hour to form PSi-COOSuc.

- Enzyme Coupling: Incubate activated surface with AChE solution (in phosphate buffer, pH 7.4) for 2 hours at 4°C. Wash thoroughly to remove unbound enzyme.

Silanization Protocol:

- Surface Hydroxylation: Oxidize PSi surface in piranha solution (3:1 H₂SO₄:H₂O₂) for 1 hour to create Si-OH terminated surface.

- Silanization: Immerse hydroxylated PSi in 2% APTES in toluene for 2 hours at room temperature to form PSi-NH₂ surface.

- Enzyme Coupling: Activate carboxylic groups on AChE using NHS/EDC, then incubate with PSi-NH₂ surface for 2 hours at 4°C [25].

Biosensor Performance and Selectivity Enhancement

Analytical Performance of Enzymatic Biosensors

Enzymatic biosensors for pesticide detection have demonstrated impressive analytical performance, often with limits of detection (LOD) significantly lower than maximum residue limits set by regulatory bodies [26]. For instance, AChE-based biosensors utilizing noble metal nanoparticles have achieved LODs as low as 1.0 nM for carbamate pesticides and 19-77 ng/L for organophosphorus pesticides in food matrices like apples and cabbage [26]. The sensitivity is markedly influenced by both the immobilization matrix and transducer type, with electrochemical transducers being most prevalent (71.18%), followed by fluorescent (13.55%) and colorimetric (8.47%) detection [26].

Addressing Selectivity Challenges

A significant limitation of enzyme-based biosensors, particularly those utilizing AChE, is their group selectivity rather than compound-specific detection. Various strategies have been developed to enhance selectivity:

- Chemometric Approaches: Combining multiple biosensors with different enzyme isoforms or mutants in array formats, with data interpretation using artificial neural networks (ANNs) or partial least squares (PLS) algorithms. This approach has successfully discriminated between paraoxon and carbofuran in binary mixtures with prediction errors of 0.4 μg/L and 0.5 μg/L, respectively [22].